Given the reputation that salmonella (for those who don’t know, it’s a toxin you don’t want to find in your food) has, a nanoparticle which mimics its effects has a certain cachet. An Aug. 22, 2016 news item on Nanowerk,

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have designed a nanoparticle that mimics the bacterium Salmonella and may help to counteract a major mechanism of chemotherapy resistance.

Working with mouse models of colon and breast cancer, Beth McCormick, Ph.D., and her colleagues demonstrated that when combined with chemotherapy, the nanoparticle reduced tumor growth substantially more than chemotherapy alone.

Credit: Rocky Mountain Laboratories,NIAID,NIHColor-enhanced scanning electron micrograph showing Salmonella typhimurium (red) invading cultured human cells.

An Aug. 22, 2016 US National Institute of Cancer news release, which originated the news item, explains the research in more detail,

A membrane protein called P-glycoprotein (P-gp) acts like a garbage chute that pumps waste, foreign particles, and toxins out of cells. P-gp is a member of a large family of transporters, called ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, that are active in normal cells but also have roles in cancer and other diseases. For instance, cancer cells can co-opt P-gp to rid themselves of chemotherapeutic agents, severely limiting the efficacy of these drugs.

In previous work, Dr. McCormick and her colleagues serendipitously discovered that Salmonella enterica, a bacterium that causes food poisoning, decreases the amount of P-gp on the surface of intestinal cells. Because Salmonella has the capacity to grow selectively in cancer cells, the researchers wondered whether there was a way to use the bacterium to counteract chemotherapy resistance caused by P-gp.

“While trying to understand how Salmonella invades the human host, we made this other observation that may be relevant to cancer therapeutics and multidrug resistance,” explained Dr. McCormick.

Salmonella and Cancer Cells

To determine the specific bacterial component responsible for reducing P-gp levels, the researchers engineered multiple Salmonella mutant strains and tested their effect on P-gp levels in colon cells. They found that a Salmonella strain lacking the bacterial protein SipA was unable to reduce P-gp levels in the colon of mice or in a human colon cancer cell line. Salmonella secretes SipA, along with other proteins, to help the bacterium invade human cells.

The researchers then showed that treatment with SipA protein alone decreased P-gp levels in cell lines of human colon cancer, breast cancer, bladder cancer, and lymphoma.

Because P-gp can pump drugs out of cells, the researchers next sought to determine whether SipA treatment would prevent cancer cells from expelling chemotherapy drugs.

When they treated human colon cancer cells with the chemotherapy agents doxorubicin or vinblastine, with or without SipA, they found that the addition of SipA increased drug retention inside the cells. SipA also increased the cancer cells’ sensitivity to both drugs, suggesting that it could possibly be used to enhance chemotherapy.

“Through millions of years of co-evolution, Salmonella has figured out a way to remove this transporter from the surface of intestinal cells to facilitate host infection,” said Dr. McCormick. “We capitalized on the organism’s ability to perform that function.”

A Nanoparticle Mimic

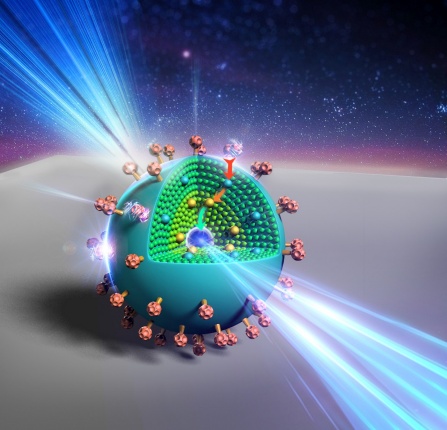

It would not be feasible to infect people with the bacterium, and SipA on its own will likely deteriorate quickly in the bloodstream, coauthor Gang Han, Ph.D., of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, explained in a press release. The researchers therefore fused SipA to gold nanoparticles, generating what they refer to as a nanoparticle mimic of Salmonella. They designed the nanoparticle to enhance the stability of SipA, while retaining its ability to interact with other proteins.

In an effort to target tumors without harming healthy tissues, the researchers used a nanoparticle of specific size that should only be able to access the tumor tissue due to its “leaky” architecture. “Because of this property, we are hoping to be able to avoid negative effects to healthy tissues,” said Dr. McCormick. Another benefit of this technology is that the nanoparticle can be modified to enhance tumor targeting and minimize the potential for side effects, she added.

The researchers showed that this nanoparticle was 100 times more effective than SipA protein alone at reducing P-gp levels in a human colon cancer cell line. The enhanced function of the nanoparticle is likely due to stabilization of SipA, explained the researchers.

The team then tested the nanoparticle in a mouse model of colon cancer, because this cancer type is known to express high levels of P-gp. When they treated tumor-bearing mice with the nanoparticle plus doxorubicin, P-gp levels dropped and the tumors grew substantially less than in mice treated with the nanoparticle or doxorubicin alone. The researchers observed similar results in a mouse model of human breast cancer.

There are concerns about the potential effect of nanoparticles on normal tissues. “P-gp has evolved as a defense mechanism” to rid healthy cells of toxic molecules, said Suresh Ambudkar, Ph.D., deputy chief of the Laboratory of Cell Biology in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. It plays an important role in protecting cells of the blood-brain barrier, liver, testes, and kidney. “So when you try to interfere with that, you may create problems,” he said.

The researchers, however, found no evidence of nanoparticle accumulation in the brain, heart, kidney, or lungs of mice, nor did it appear to cause toxicity. They did observe that the nanoparticles accumulated in the liver and spleen, though this was expected because these organs filter the blood, said Dr. McCormick.

Moving Forward

The research team is moving forward with preclinical studies of the SipA nanoparticle to test its safety and toxicity, and to establish appropriate dosage levels.

However, Dr. Ambudkar noted, “the development of drug resistance in cancer cells is a multifactorial process. In addition to the ABC transporters, other phenomena are involved, such as drug metabolism.” And because there is a large family of ABC transporters, one transporter can compensate if another is blocked, he explained.

For the last 25 years, clinical trials with drugs that inhibit P-gp have failed to overcome chemotherapy resistance, Dr. Ambudkar said. Tackling the issue of multidrug resistance in cancer, he continued, “is not something that can be solved easily.”

Dr. McCormick and her team are also pursuing research to better characterize and understand the biology of SipA. “We are not naïve about the complexity of the problem,” she said. “However, if we know more about the biology, we believe we can ultimately make a better drug.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Salmonella nanoparticle mimic overcomes multidrug resistance in tumours by Regino Mercado-Lubo, Yuanwei Zhang, Liang Zhao, Kyle Rossi, Xiang Wu, Yekui Zou, Antonio Castillo, Jack Leonard, Rita Bortell, Dale L. Greiner, Leonard D. Shultz, Gang Han, & Beth A. McCormick. Nature Communications 7, Article number: 12225 doi:10.1038/ncomms12225 Published 25 July 2016

This paper is open access.