Part of neuromorphic computing’s appeal is the promise of using less energy because, as it turns out, the human brain uses small amounts of energy very efficiently. A team of researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst have developed function in the same range of voltages as the human brain. From an April 20, 2020 news item on ScienceDaily,

Only 10 years ago, scientists working on what they hoped would open a new frontier of neuromorphic computing could only dream of a device using miniature tools called memristors that would function/operate like real brain synapses.

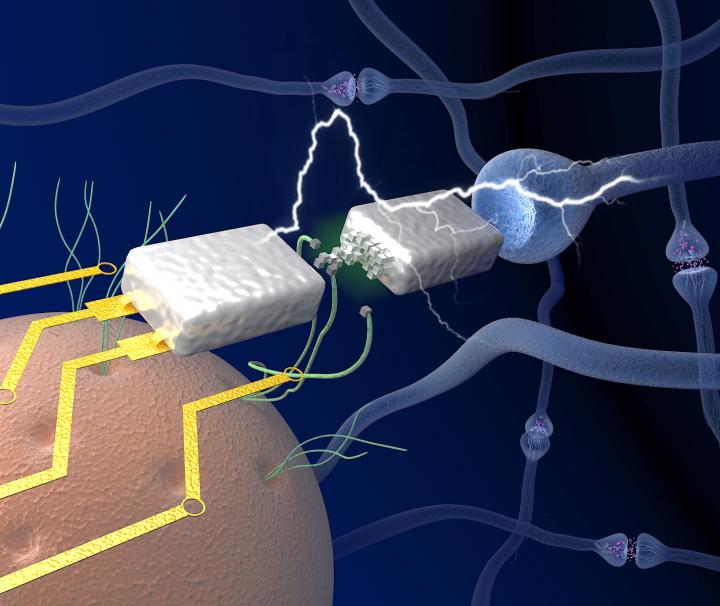

But now a team at the University of Massachusetts Amherst has discovered, while on their way to better understanding protein nanowires, how to use these biological, electricity conducting filaments to make a neuromorphic memristor, or “memory transistor,” device. It runs extremely efficiently on very low power, as brains do, to carry signals between neurons. Details are in Nature Communications.

An April 20, 2020 University of Massachusetts at Amherst news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news items, dives into detail about how these researchers were able to achieve bio-voltages,

As first author Tianda Fu, a Ph.D. candidate in electrical and computer engineering, explains, one of the biggest hurdles to neuromorphic computing, and one that made it seem unreachable, is that most conventional computers operate at over 1 volt, while the brain sends signals called action potentials between neurons at around 80 millivolts – many times lower. Today, a decade after early experiments, memristor voltage has been achieved in the range similar to conventional computer, but getting below that seemed improbable, he adds.

Fu reports that using protein nanowires developed at UMass Amherst from the bacterium Geobacter by microbiologist and co-author Derek Lovely, he has now conducted experiments where memristors have reached neurological voltages. Those tests were carried out in the lab of electrical and computer engineering researcher and co-author Jun Yao.

Yao says, “This is the first time that a device can function at the same voltage level as the brain. People probably didn’t even dare to hope that we could create a device that is as power-efficient as the biological counterparts in a brain, but now we have realistic evidence of ultra-low power computing capabilities. It’s a concept breakthrough and we think it’s going to cause a lot of exploration in electronics that work in the biological voltage regime.”

Lovely points out that Geobacter’s electrically conductive protein nanowires offer many advantages over expensive silicon nanowires, which require toxic chemicals and high-energy processes to produce. Protein nanowires also are more stable in water or bodily fluids, an important feature for biomedical applications. For this work, the researchers shear nanowires off the bacteria so only the conductive protein is used, he adds.

Fu says that he and Yao had set out to put the purified nanowires through their paces, to see what they are capable of at different voltages, for example. They experimented with a pulsing on-off pattern of positive-negative charge sent through a tiny metal thread in a memristor, which creates an electrical switch.

They used a metal thread because protein nanowires facilitate metal reduction, changing metal ion reactivity and electron transfer properties. Lovely says this microbial ability is not surprising, because wild bacterial nanowires breathe and chemically reduce metals to get their energy the way we breathe oxygen.

As the on-off pulses create changes in the metal filaments, new branching and connections are created in the tiny device, which is 100 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair, Yao explains. It creates an effect similar to learning – new connections – in a real brain. He adds, “You can modulate the conductivity, or the plasticity of the nanowire-memristor synapse so it can emulate biological components for brain-inspired computing. Compared to a conventional computer, this device has a learning capability that is not software-based.”

Fu recalls, “In the first experiments we did, the nanowire performance was not satisfying, but it was enough for us to keep going.” Over two years, he saw improvement until one fateful day when his and Yao’s eyes were riveted by voltage measurements appearing on a computer screen.

“I remember the day we saw this great performance. We watched the computer as current voltage sweep was being measured. It kept doing down and down and we said to each other, ‘Wow, it’s working.’ It was very surprising and very encouraging.”

Fu, Yao, Lovely and colleagues plan to follow up this discovery with more research on mechanisms, and to “fully explore the chemistry, biology and electronics” of protein nanowires in memristors, Fu says, plus possible applications, which might include a device to monitor heart rate, for example. Yao adds, “This offers hope in the feasibility that one day this device can talk to actual neurons in biological systems.”

That last comment has me wondering about why you would want to have your device talk to actual neurons. For neuroprosthetics perhaps?

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Bioinspired bio-voltage memristors by Tianda Fu, Xiaomeng Liu, Hongyan Gao, Joy E. Ward, Xiaorong Liu, Bing Yin, Zhongrui Wang, Ye Zhuo, David J. F. Walker, J. Joshua Yang, Jianhan Chen, Derek R. Lovley & Jun Yao. Nature Communications volume 11, Article number: 1861 (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15759-y Published: 20 April 2020

This paper is open access.

There is an illustration of the work