Learning to distinguish your left from your right isn’t all that easy for children. It’s also remarkably easy to lose the ability (temporarily) to make that distinction if you start experimenting with certain kinds of brain repatterning. However, the distinctions are important not only in daily life but in biology too according to a June 26, 2013 news item on Nanowerk,

In chemical reactions, left and right can make a big difference. A “left-handed” molecule of a particular chemical composition could be an effective drug, while its mirror-image “right-handed” counterpart could be completely inactive. That’s because, in biology, “left” and “right” molecular designs are crucial: Living organisms are made only from left-handed amino acids. So telling the two apart is important—but difficult.

Now, a team of scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and Ohio University has developed a new, simpler way to discern molecular handedness, known as chirality.

The June 26, 2013 Brookhaven National Laboratory news release, which originated the news item, describes the new technique for distinguishing left- from right-handed molecules,

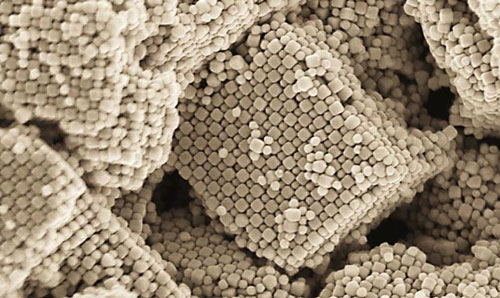

They used gold-and-silver cubic nanoparticles to amplify the difference in left- and right-handed molecules’ response to a particular kind of light. The study, described in the journal NanoLetters, provides the basis for a new way to probe the effects of handedness in molecular interactions with unprecedented sensitivity.

…

The scientists knew that left- and right-handed chiral molecules would interact differently with “circularly polarized” light—where the direction of the electrical field rotates around the axis of the beam. This idea is similar to the way polarized sunglasses filter out reflected glare unlike ordinary lenses.

Other scientists have detected this difference, called “circular dichroism,” in organic molecules’ spectroscopic “fingerprints”—detailed maps of the wavelengths of light absorbed or reflected by the sample. But for most chiral biomolecules and many organic molecules, this “CD” signal is in the ultraviolet range of the electromagnetic spectrum, and the signal is often weak. The tests thus require significant amounts of material at impractically high concentrations.

The team was encouraged they might find a way to enhance the signal by recent experiments showing that coupling certain molecules with metallic nanoparticles could greatly increase their response to light. Theoretical work even suggested that these so-called plasmonic particles—which induce a collective oscillation of the material’s conductive electrons, leading to stronger absorption of a particular wavelength—could bump the signal into the visible light portion of the spectroscopic fingerprint, where it would be easier to measure.

The group experimented with different shapes and compositions of nanoparticles, and found that cubes with a gold center surrounded by a silver shell are not only able to show a chiral optical signal in the near-visible range, but even more striking, were effective signal amplifiers. For their test biomolecule, they used synthetic strands of DNA—a molecule they were familiar with using as “glue” for sticking nanoparticles together.

When DNA was attached to the silver-coated nanocubes, the signal was approximately 100 times stronger than it was for free DNA in the solution. That is, the cubic nanoparticles allowed the scientists to detect the optical signal from the chiral molecules (making them “visible”) at 100 times lower concentrations.

…

The observed amplification of the circular dichroism signal is a consequence of the interaction between the plasmonic particles and the “exciton,” or energy absorbing, electrons within the DNA-nanocube complex, the scientists explained.

“This research could serve as a promising platform for ultrasensitive sensing of chiral molecules and their transformations in synthetic, biomedical, and pharmaceutical applications,” Lu [Fang Lu, the first author on the paper] said.

“In addition,” said Gang [Oleg Gang, a researcher at Brookhaven’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials and lead author on the paper], “our approach offers a way to fabricate, via self-assembly, discrete plasmonic nano-objects with a chiral optical response from structurally non-chiral nano-components. These chiral plasmonic objects could greatly enhance the design of metamaterials and nano-optics for applications in energy harvesting and optical telecommunications.”

I last mentioned chirality in the context of work being done with controlling the chirality of carbon nanotubes at Finland’s Aalto University in an April 30 , 2013 posting.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper published by the Brookhaven National Laboratory and Ohio University,

Discrete Nanocubes as Plasmonic Reporters of Molecular Chirality by Fang Lu, Ye Tian, Mingzhao Liu, Dong Su, Hui Zhang, Alexander O. Govorov, and Oleg Gang. Nano Lett., Article ASAP

DOI: 10.1021/nl401107g Publication Date (Web): June 18, 2013

Copyright © 2013 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.