A team at Michigan Technological University (Michigan Tech) has developed a simple technique for clearing nanoparticles from water according to a Dec. 10, 2015 news item on Nanotechnology Now,

Nano implies small—and that’s great for use in medical devices, beauty products and smartphones—but it’s also a problem. The tiny nanoparticles, nanowires, nanotubes and other nanomaterials that make up our technology eventually find their way into water. The Environmental Protection Agency says more 1,300 commercial products use some kind of nanomaterial. And we just don’t know the full impact on health and the environment.

A Dec. 10, 2015 Michigan Tech news release, which originated the news item, describes the concept and the research in more detail,

“Look at plastic,” says Yoke Khin Yap, a professor of physics at Michigan Technological University. “These materials changed the world over the past decades—but can we clean up all the plastic in the ocean? We struggle to clean up meter-scale plastics, so what happens when we need to clean on the nano-scale?”

…

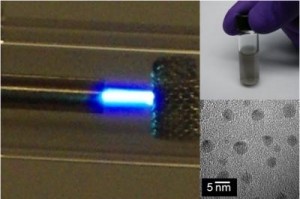

The method sounds like a salad dressing recipe: take water, sprinkle in nanomaterials, add oil and shake.

Water and oil don’t mix, of course, but shaking them together is what makes salad dressing so great. Only instead of emulsifying and capturing bits of shitake or basil in tiny olive oil bubbles, this mixture grabs nanomaterials.

Dongyan Zhang, a research professor of physics at Michigan Tech, led the experiments, which covered tests on carbon nanotubes, graphene, boron nitride nanotubes, boron nitride nanosheets and zinc oxide nanowires. Those are used in everything from carbon fiber golf clubs to sunscreen.

“These materials are very, very tiny, and that means if you try to remove them and clean them out of contaminated water, that it’s quite difficult,” Zhang says, adding that techniques like filter paper or meshes often don’t work.

What makes shaking work is the shape of one- and two-dimensional nanomaterials. As the oil and water separate after some rigorous shaking, the wires, tubes and sheets settle at the bottom of the oil, just above the water. The oils trap them. However, zero-dimensional nanomaterials, such as nanospheres do not get trapped.

The researchers, according to the news release, are attempting to anticipate the potential contamination of our water supply by nanomaterials and provide a solution before it happens,

We don’t have to wait until the final vote is in on whether nanomaterials have a positive or negative impact on people’s health and environmental health. With the simplicity of this technique, and how prolific nanomaterials are becoming, removing nanomaterials makes sense. Also, finding ways to effectively remove nanomaterials sooner rather than later could improve the technology’s market potential.

“Ideally for a new technology to be successfully implemented, it needs to be shown that the technology does not cause adverse effects to the environment,” Yap, Zhang and their co-authors write. “Therefore, unless the potential risks of introducing nanomaterials into the environment are properly addressed, it will hinder the industrialization of products incorporating nanotechnology.”

Purifying water and greening nanotechnology could be as simple as shaking a vial of water and oil.

Here’s a video about the research supplied by Michigan Tech,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Simple and Universal Technique To Extract One- and Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials from Contaminated Water by Bishnu Tiwari, Dongyan Zhang, Dustin Winslow, Chee Huei Lee, Boyi Hao, and Yoke Khin Yap. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2015, 7 (47), pp 26108–26116 DOI: 10.1021/acsami.5b07542 Publication Date (Web): November 9, 2015

Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.