A Jan. 4, 2021 news item on Nanowerk describes new insights into nanoscale catalysts derived from work at the US Argonne National Laboratory,

Catalysts are integral to countless aspects of modern society. By speeding up important chemical reactions, catalysts support industrial manufacturing and reduce harmful emissions. They also increase efficiency in chemical processes for applications ranging from batteries and transportation to beer and laundry detergent.

As significant as catalysts are, the way they work is often a mystery to scientists. Understanding catalytic processes can help scientists develop more efficient and cost-effective catalysts. In a recent study, scientists from University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory discovered that, during a chemical reaction that often quickly degrades catalytic materials, a certain type of catalyst displays exceptionally high stability and durability.

The catalysts in this study are alloy nanoparticles, or nanosized particles made up of multiple metallic elements, such as cobalt, nickel, copper and platinum. These nanoparticles could have multiple practical applications, including water-splitting to generate hydrogen in fuel cells; reduction of carbon dioxide by capturing and converting it into useful materials like methanol; more efficient reactions in biosensors to detect substances in the body; and solar cells that produce heat, electricity and fuel more effectively.

…

A January 4, 2021 Argonne National Laboratory news release (also on EurekAlert) by Savannah Mitchem fills in some details,

In this study, the scientists investigated “high-entropy” (highly stable) alloy nanoparticles. The team of researchers, led by Reza Shahbazian-Yassar at UIC, used Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials (CNM), a DOE Office of Science user facility, to characterize the particles’ compositions during oxidation, a process that degrades the material and reduces its usefulness in catalytic reactions.

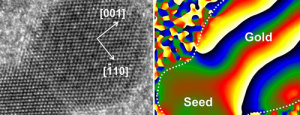

“Using gas flow transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at CNM, we can capture the whole oxidation process in real time and at very high resolution,” said scientist Bob Song from UIC, a lead scientist on the study. “We found that the high-entropy alloy nanoparticles are able to resist oxidation much better than general metal particles.”

To perform the TEM, the scientists embedded the nanoparticles into a silicon nitride membrane and flowed different types of gas through a channel over the particles. A beam of electrons probed the reactions between the particles and the gas, revealing the low rate of oxidation and the migration of certain metals — iron, cobalt, nickel and copper — to the particles’ surfaces during the process.

“Our objective was to understand how fast high-entropy materials react with oxygen and how the chemistry of nanoparticles evolves during such a reaction,” said Shahbazian-Yassar, UIC professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at the College of Engineering.

According to Shahbazian-Yassar, the discoveries made in this research could benefit many energy storage and conversion technologies, such as fuel cells, lithium-air batteries, supercapacitors and catalyst materials. The nanoparticles could also be used to develop corrosion-resistant and high-temperature materials.

“This was a successful showcase of how CNM’s capabilities and services can meet the needs of our collaborators,” said Argonne’s Yuzi Liu, a scientist at CNM. “We have state-of-the-art facilities, and we want to deliver state-of-the-art science as well.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

In Situ Oxidation Studies of High-Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles by Boao Song, Yong Yang, Muztoba Rabbani, Timothy T. Yang, Kun He, Xiaobing Hu, Yifei Yuan, Pankaj Ghildiyal, Vinayak P. Dravid, Michael R. Zachariah, Wissam A. Saidi, Yuzi Liu, and Reza Shahbazian-Yassar. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 11, 15131–15143 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c05250 Publication Date:October 20, 2020 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

Below is one of my favourite types of video work, a ‘blob video’ from the University of Illinois showing the alloy nanoparticles as they oxidate,

![Cetyltrimethylammonium-ion-coated gold nanoparticles before (top) and after (bottom) 500 seconds of electron-beam exposure inside a TEM liquid cell at 200 kV. Scale bar: 100 nm. [downloaded from http://nano.anl.gov/news/highlights/2013_gold_nanoparticles.html]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Argonne_Gold_NP.png)