Jeff Bittel thank you for a story (Mar. 26, 2013 on Slate) about Rachel Levy and the website where she gently blows up the notion/stereotype that older women don’t understand science and technology and that they are too old to learn (Note: A link has been removed),

Is your grandmother a particle physicist? Did she help the Navy build submarines or make concoctions of chlorine gas on the family’s front porch? Or is she a mathematician, inventor, or engineer? If so, then baby, your grandma’s got STEM.

Grandma Got STEM is a celebration of women working in and contributing to the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. It is also designed to combat the doting, fumbling, pie-making stereotype of grandmatrons.

That’s why Rachel Levy, an associate professor of mathematics at Harvey Mudd College, is collecting the stories of grandmas across the various fields of STEM. She first got the idea after hearing someone utter the phrase, “Just explain it like you would to your grandma.”

At first blush, such a thing seems harmless. But think about what it means—basically, all older women are stupid.

“For two or three years I thought about how I could address this issue without just making people angry and more inclined to use the phrase,” Levy told me. “If I could come up with a million examples of grandmothers who were tech-savvy, people wouldn’t say it anymore because it wouldn’t be apt.”

While attending the conference ScienceOnline this year, Levy realized she could harness the power of the Internet to collect stories and showcase them. So far, she’s been able to upload at least one grandma a day for about a month and a half—and the stories keep pouring in. Levy’s aim so far is to be as inclusive as possible. She’s accepting any grandma currently or previously involved in STEM. They can submit themselves or you can submit for them. Heck, they don’t even have to have children with children, per se. Age’ll do just fine.

Bittel might want to reconsider that bit about children and children with children. That can be a touchy topic.

Levy’s solution was to create the Grandma Got STEM website. From the Mar. 27, 2013 posting about Mary Vellos Klonowski,

Thank you to undergraduate Math/Computer Science Major Joey Klonowski, who submitted this post about his grandmother:

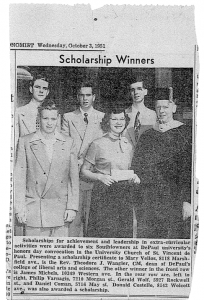

This photo is from the October 3, 1951 edition of The Southtown Economist, a daily newspaper on the South Side of Chicago, when my grandmother, Mary Klonowski, was 18. She attended DePaul University against the wishes of her father, who didn’t want his daughters to be college educated. She received a BS from DePaul in 1954 and was the only woman chemistry major in her class. She later earned a master’s in mathematics education and became a high school math teacher. She is now 80 years old and still working as a substitute teacher.

There are a lot of stories (covering quite the range of grannies) on the site. Levy is asking for international submissions as well,

Seeking international submissions!

You can help promote this project by sharing the posts on your blog, Facebook wall, or by retweeting them.

The project has readers from more than 100 countries, but submissions from only a few. Please help make this blog an international effort by submitting posts or encouraging others to post.

Call for submissions – short

Know any geeky grannies? Seeking submissions for Grandma got STEM. Email name+pic+story to ggstem@hmc.edu.

Call for submissions – long

Call for submissions – Grandma got STEM. Are you a grandmother working in a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) – related field? Know any geeky grannies? Email name+pic+story/remembrance to Rachel Levy: ggstem (at) hmc (dot) edu. Follow on Twitter: @mathcirque #ggstem Project site:http://ggstem.wordpress.com

Presumably, the submissions need to be in English.

Getting back to Bittel’s Slate article, he mentions Foldit (here’s my first piece in an Aug. 6, 2010 posting [scroll down about 1/2 way]), a protein-folding game which has generated some very exciting science. He also notes some of that science was generated by older, ‘uneducated’ women. Bittel linked to Jeff Howe’s Feb. 27, 2012 article about Foldit and other crowdsourced science projects for Slate where I found this very intriguing bit,

“You’d think a Ph.D. in biochemistry would be very good at designing protein molecules,” says Zoran Popović, the University of Washington game designer behind Foldit. Not so. “Biochemists are good at other things. But Foldit requires a narrow, deeper expertise.”

Or as it turns out, more than one. Some gamers have a preternatural ability to recognize patterns, an innate form of spatial reasoning most of us lack. Others—often “grandmothers without a high school education,” says Popovic—exercise a particular social skill. “They’re good at getting people unstuck. They get them to approach the problem differently.” What big pharmaceutical company would have anticipated the need to hire uneducated grandmothers? (I know a few, if Eli Lilly HR is thinking of rejiggering its recruitment strategy.) [emphases mine]

There’s an interesting question and I didn’t see it answered in Howe’s article. What kind of grandmother who doesn’t have high school graduation joins a protein-folding game? I ask because neither of my parents had or have a high school education. Neither of them would have joined the game as neither would have had the confidence.

What I’ve tried to present here is a range of possibilities regarding age and education. Being older (female especially but also male, on occasion) doesn’t equal stupidity. As for education, I’ve never found that having high school graduation or a university degree(s) to be a guarantor of an exciting intellect. I mention these two points because it seems to me that people are being ranked as to age and education in ways that are unnecessarily exclusionary. Thank goodness for games like Foldit and websites like Grandma’s Got STEM which suggest alternatives to this relentless and ruthless form of ranking which disallows participation from the great bulk of us.