So we’re still stuck in 20th century concepts about artificial intelligence (AI), eh? Sean Captain’s February 21, 2020 article (for Fast Company) about the new AI exhibit in San Francisco suggests that artists can help us revise our ideas (Note: Links have been removed),

Though we’re well into the age of machine learning, popular culture is stuck with a 20th century notion of artificial intelligence. While algorithms are shaping our lives in real ways—playing on our desires, insecurities, and suspicions in social media, for instance—Hollywood is still feeding us clichéd images of sexy, deadly robots in shows like Westworld and Star Trek Picard.

The old-school humanlike sentient robot “is an important trope that has defined the visual vocabulary around this human-machine relationship for a very long period of time,” says Claudia Schmuckli, curator of contemporary art and programming at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. It’s also a naïve and outdated metaphor, one she is challenging with a new exhibition at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, called Uncanny Valley, that opens on February 22 [2020].

The show’s name [Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI] is a kind of double entendre referencing both the dated and emerging conceptions of AI. Coined in the 1970s, the term “uncanny valley” describes the rise and then sudden drop off of empathy we feel toward a machine as its resemblance to a human increases. Putting a set of cartoony eyes on a robot may make it endearing. But fitting it with anatomically accurate eyes, lips, and facial gestures gets creepy. As the gap between the synthetic and organic narrows, the inability to completely close that gap becomes all the more unsettling.

But the artists in this exhibit are also looking to another valley—Silicon Valley, and the uncanny nature of the real AI the region is building. “One of the positions of this exhibition is that it may be time to rethink the coordinates of the Uncanny Valley and propose a different visual vocabulary,” says Schmuckli.

…

From Captain’s February 21, 2020 article,

… the resemblance to humans is only synthetic-skin deep. Bina48 can string together a long series of sentences in response to provocative questions from Dinkins, such as, “Do you know racism?” But the answers are sometimes barely intelligible, or at least lack the depth and nuance of a conversation with a real human. The robot’s jerky attempts at humanlike motion also stand in stark contrast to Dinkins’s calm bearing and fluid movement. Advanced as she is by today’s standards, Bina48 is tragically far from the sci-fi concept of artificial life. Her glaring shortcomings hammer home why the humanoid metaphor is not the right framework for understanding at least today’s level of artificial intelligence.

For anybody who has more curiosity about the ‘uncanny valley’, there’s this Wikipedia entry.

For more details about the’ Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI’ exhibition there’s this September 26, 2019 de Young museum news release,

What are the invisible mechanisms of current forms of artificial intelligence (AI)? How is AI impacting our personal lives and socioeconomic spheres? How do we define intelligence? How do we envision the future of humanity?

SAN FRANCISCO (September 26, 2019) — As technological innovation continues to shape our identities and societies, the question of what it means to be, or remain human has become the subject of fervent debate. Taking advantage of the de Young museum’s proximity to Silicon Valley, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI arrives as the first major exhibition in the US to explore the relationship between humans and intelligent machines through an artistic lens. Organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, with San Francisco as its sole venue, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI will be on view from February 22 to October 25, 2020.

“Technology is changing our world, with artificial intelligence both a new frontier of possibility but also a development fraught with anxiety,” says Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI brings artistic exploration of this tension to the ground zero of emerging technology, raising challenging questions about the future interface of human and machine.”

The exhibition, which extends through the first floor of the de Young and into the museum’s sculpture garden, explores the current juncture through philosophical, political, and poetic questions and problems raised by AI. New and recent works by an intergenerational, international group of artists and activist collectives—including Zach Blas, Ian Cheng, Simon Denny, Stephanie Dinkins, Forensic Architecture, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Pierre Huyghe, Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, Agnieszka Kurant, Lawrence Lek, Trevor Paglen, Hito Steyerl, Martine Syms, and the Zairja Collective—will be presented.

The Uncanny Valley

In 1970 Japanese engineer Masahiro Mori introduced the concept of the “uncanny valley” as a terrain of existential uncertainty that humans experience when confronted with autonomous machines that mimic their physical and mental properties. An enduring metaphor for the uneasy relationship between human beings and lifelike robots or thinking machines, the uncanny valley and its edges have captured the popular imagination ever since. Over time, the rapid growth and affordability of computers, cloud infrastructure, online search engines, and data sets have fueled developments in machine learning that fundamentally alter our modes of existence, giving rise to a newly expanded uncanny valley.

“As our lives are increasingly organized and shaped by algorithms that track, collect, evaluate, and monetize our data, the uncanny valley has grown to encompass the invisible mechanisms of behavioral engineering and automation,” says Claudia Schmuckli, Curator in Charge of Contemporary Art and Programming at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “By paying close attention to the imminent and nuanced realities of AI’s possibilities and pitfalls, the artists in the exhibition seek to thicken the discourse around AI. Although fables like HBO’s sci-fi drama Westworld, or Spike Jonze’s feature film Her still populate the collective imagination with dystopian visions of a mechanized future, the artists in this exhibition treat such fictions as relics of a humanist tradition that has little relevance today.”

In Detail

Ian Cheng’s digitally simulated AI creature BOB (Bag of Beliefs) reflects on the interdependency of carbon and silicon forms of intelligence. An algorithmic Tamagotchi, it is capable of evolution, but its growth, behavior, and personality are molded by online interaction with visitors who assume collective responsibility for its wellbeing.

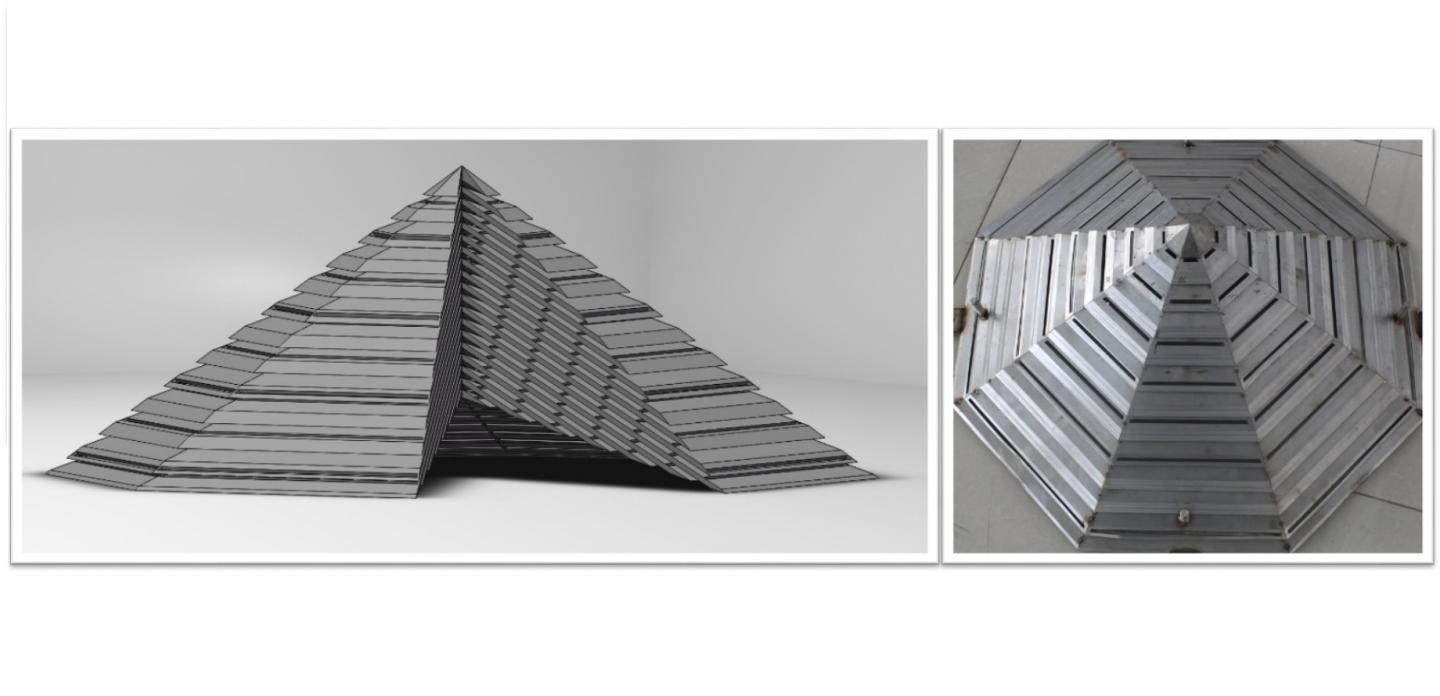

In A.A.I. (artificial artificial intelligence), an installation of multiple termite mounds of colored sand, gold, glitter and crystals, Agnieszka Kurant offers a vibrant critique of new AI economies, with their online crowdsourcing marketplace platforms employing invisible armies of human labor at sub-minimum wages.

Simon Denny ‘s Amazon worker cage patent drawing as virtual King Island Brown Thornbill cage (US 9,280,157 B2: “System and method for transporting personnel within an active workspace”, 2016) (2019) also examines the intersection of labor, resources, and automation. He presents 3-D prints and a cage-like sculpture based on an unrealized machine patent filed by Amazon to contain human workers. Inside the cage an augmented reality application triggers the appearance of a King Island Brown Thornbill — a bird on the verge of extinction; casting human labor as the proverbial canary in the mine. The humanitarian and ecological costs of today’s data economy also informs a group of works by the Zairja Collective that reflect on the extractive dynamics of algorithmic data mining.

Hito Steyerl addresses the political risks of introducing machine learning into the social sphere. Her installation The City of Broken Windows presents a collision between commercial applications of AI in urban planning along with communal and artistic acts of resistance against neighborhood tipping: one of its short films depicts a group of technicians purposefully smashing windows to teach an algorithm how to recognize the sound of breaking glass, and another follows a group of activists through a Camden, NJ neighborhood as they work to keep decay at bay by replacing broken windows in abandoned homes with paintings.

Addressing the perpetuation of societal biases and discrimination within AI, Trevor Paglen’s They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead…(SD18), presents a large gridded installation of more than three thousand mugshots from the archives of the American National Standards Institute. The institute’s collections of such images were used to train ealry facial-recognition technologies — without the consent of those pictured. Lynn Hershman Leeson’s new installation Shadow Stalker critiques the problematic reliance on algorithmic systems, such as the military forecasting tool Predpol now widely used for policing, that categorize individuals into preexisting and often false “embodied metrics.”

Stephanie Dinkins extends the inquiry into how value systems are built into AI and the construction of identity in Conversations with Bina48, examining the social robot’s (and by extension our society’s) coding of technology, race, gender and social equity. In the same territory, Martine Syms posits AI as a “shamespace” for misrepresentation. For Mythiccbeing she has created an avatar of herself that viewers can interact with through text messaging. But unlike service agents such as Siri and Alexa, who readily respond to questions and demands, Syms’s Teeny is a contrarious interlocutor, turning each interaction into an opportunity to voice personal observations and frustrations about racial inequality and social injustice.

Countering the abusive potential of machine learning, Forensic Architecture pioneers an application to the pursuit of social justice. Their proposition of a Model Zoo marks the beginnings of a new research tool for civil society built of military vehicles, missile fragments, and bomb clouds—evidence of human-rights violations by states and militaries around the world. Christopher Kulendran Thomas’s video Being Human, created in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, poses the philosophical question of what it means to be human when machines are able to synthesize human understanding ever more convincingly. Set in Sri Lanka, it employs AI-generated characters of singer Taylor Swift and artist Oscar Murillo to reflect on issues of individual authenticity, collective sovereignty, and the future of human rights.

Lawrence Lek’s sci-fi-inflected film Aidol, which explores the relationship between algorithmic automation and human creativity, projects this question into the future. It transports the viewer into the computer-generated “sinofuturist” world of the 2065 eSports Olympics: when the popular singer Diva enlists the super-intelligent Geomancer to help her stage her artistic comeback during the game’s halftime show, she unleashes an existential and philosophical battle that explodes the divide between humans and machines.

The Doors, a newly commissioned installation by Zach Blas, by contrast shines the spotlight back onto the present and on the culture and ethos of Silicon Valley — the ground zero for the development of AI. Inspired by the ubiquity of enclosed gardens on tech campuses, he has created an artificial garden framed by a six-channel video projected on glass panes that convey a sense of algorithmic psychedelia aiming to open new “doors of perception.” While luring visitors into AI’s promises, it also asks what might become possible when such glass doors begin to crack.

Unveiled in late spring Pierre Huyghe‘s Exomind (Deep Water), a sculpture of a crouched female nude with a live beehive as its head will be nestled within the museum’s garden. With its buzzing colony pollinating the surrounding flora, it offers a poignant metaphor for the modeling of neural networks on the biological brain and an understanding of intelligence as grounded in natural forms and processes.

…

The Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI event page features a link to something unexpected 9scroll down about 40% of the way), a Statement on Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture,

On Thursday, February 13 [2020], Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture had his travel authorization to the United States revoked due to an “algorithm” that identified him as a security threat.

He was meant to be in the United States promoting multiple exhibitions including Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, opening on February 22 [2020] at the de Young museum in San Francisco.

Since 2018, Forensic Architecture has used machine learning / AI to aid in humanitarian work, using synthetic images—photorealistic digital renderings based around 3-D models—to train algorithmic classifiers to identify tear gas munitions and chemical bombs deployed against protesters worldwide, including in Hong Kong, Chile, the US, Venezuela, and Sudan.

Their project, Model Zoo, on view in Uncanny Valley represents a growing collection of munitions and weapons used in conflict today and the algorithmic models developed to identify them. It shows a collection of models being used to track and hold accountable human rights violators around the world. The piece joins work by 14 contemporary artists reflecting on the philosophical and political consequences of the application of AI into the social sphere.

We are deeply saddened that Weizman will not be allowed to travel to celebrate the opening of the exhibition. We stand with him and Forensic Architecture’s partner communities who continue to resist violent states and corporate practices, and who are increasingly exposed to the regime of “security algorithms.”

—Claudia Schmuckli, Curator-in-Charge, Contemporary Art & Programming, & Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

There is a February 20, 2020 article (for Fast Company) by Eyal Weizman chronicling his experience with being denied entry by an algorithm. Do read it in its entirety (the Fast Company is itself an excerpt from Weizman’s essay) if you have the time, if not, here’s the description of how he tried to gain entry after being denied the first time,

…

The following day I went to the U.S. Embassy in London to apply for a visa. In my interview, the officer informed me that my authorization to travel had been revoked because the “algorithm” had identified a security threat. He said he did not know what had triggered the algorithm but suggested that it could be something I was involved in, people I am or was in contact with, places to which I had traveled (had I recently been in Syria, Iran, Iraq, Yemen, or Somalia or met their nationals?), hotels at which I stayed, or a certain pattern of relations among these things. I was asked to supply the Embassy with additional information, including 15 years of travel history, in particular where I had gone and who had paid for it. The officer said that Homeland Security’s investigators could assess my case more promptly if I supplied the names of anyone in my network whom I believed might have triggered the algorithm. I declined to provide this information.

…

I hope the exhibition is successful; it has certainly experienced a thought-provoking start.

Finally, I have often featured postings that discuss the ‘uncanny valley’. To find those postings, just use that phrase in the blog search engine. You might also went to search ‘Hiroshi Ishiguro’, a Japanese scientist and robotocist who specializes in humanoid robots.