A January 8, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily announces new work from South Korea’s Pohang University of Science & Technology (POSTECH),

The COVID-19 pandemic is raising fears of new pathogens such as new viruses or drug-resistant bacteria. To this, a Korean research team has recently drawn attention for developing the technology for removing antibiotic-resistant bacteria by controlling the surface texture of nanomaterials.

A joint research team from POSTECH and UNIST [Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology] has introduced mixed-FeCo-oxide-based surface-textured nanostructures (MTex) as highly efficient magneto-catalytic platform in the international journal Nano Letters. The team consisted of professors In Su Lee and Amit Kumar with Dr. Nitee Kumari of POSTECH’s Department of Chemistry and Professor Yoon-Kyung Cho and Dr. Sumit Kumar of UNIST’s Department of Biomedical Engineering.

…

A January 8, 2021 POSTECH press release (also on EurkeAlert), which originated the news item, delves further,

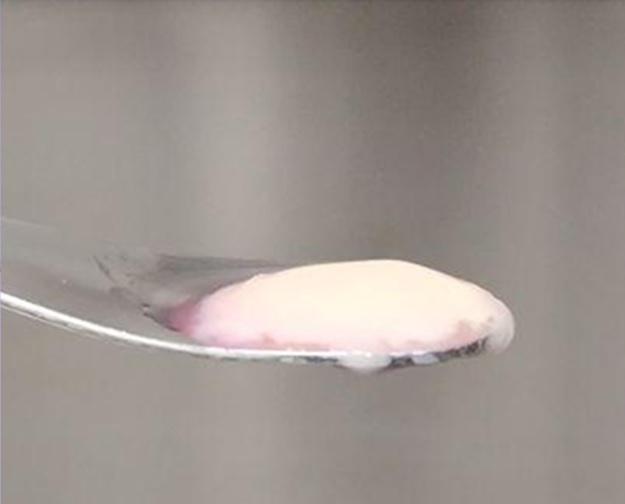

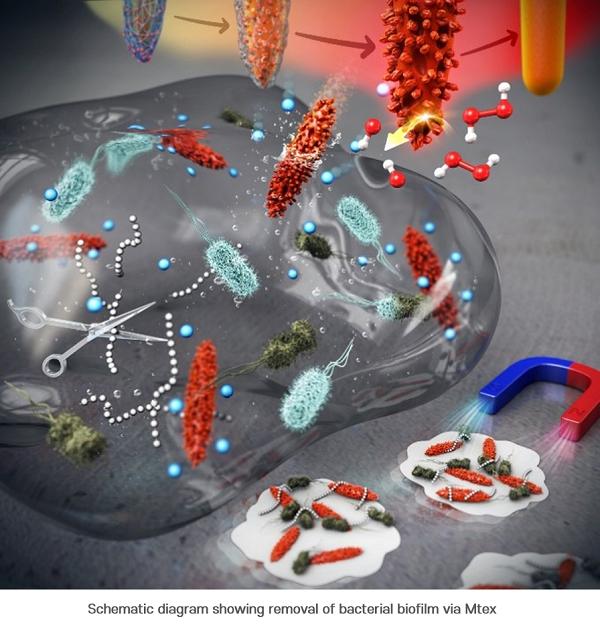

First, the researchers synthesized smooth surface nanocrystals in which various metal ions were wrapped in an organic polymer shell and heated them at a very high temperature. While annealing the polymer shell, a high-temperature solid-state chemical reaction induced mixing of other metal ions on the nanocrystal surface, creating a number of few-nm-sized branches and holes on it. This unique surface texture was found to catalyze a chemical reaction that produced reactive oxygen species (ROS) that kills the bacteria. It was also confirmed to be highly magnetic and easily attracted toward the external magnetic field. The team had discovered a synthetic strategy for converting normal nanocrystals without surface features into highly functional mixed-metal-oxide nanocrystals.

The research team named this surface topography – with branches and holes that resembles that of a ploughed field – “MTex.” This unique surface texture has been verified to increase the mobility of nanoparticles to allow efficient penetration into biofilm matrix while showing high activity in generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are lethal to bacteria.

This system produces ROS over a broad pH range and can effectively diffuse into the biofilm and kill the embedded bacteria resistant to antibiotics. And since the nanostructures are magnetic, biofilm debris can be scraped out even from the hard-to-reach microchannels.

“This newly developed MTex shows high catalytic activity, distinct from the stable smooth-surface of the conventional spinel forms,” explained Dr. Amit Kumar, one of the corresponding authors of the paper. “This characteristic is very useful in infiltrating biofilms even in small spaces and is effective in killing the bacteria and removing biofilms.”

“This research allows to regulate the surface nanotexturization, which opens up possibilities to augment and control the exposure of active sites,” remarked Professor In Su Lee who led the research. “We anticipate the nanoscale-textured surfaces to contribute significantly in developing a broad array of new enzyme-like properties at the nano-bio interface.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Surface-Textured Mixed-Metal-Oxide Nanocrystals as Efficient Catalysts for ROS Production and Biofilm Eradication by Nitee Kumari, Sumit Kumar, Mamata Karmacharya, Sateesh Dubbu, Taewan Kwon, Varsha Singh, Keun Hwa Chae, Amit Kumar, Yoon-Kyoung Cho, and In Su Lee. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 1, 279–287 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03639 Publication Date: December 11, 2020 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.