An April 22, 2015 news item on Nanowerk describes an acoustic imaging technique that’s been newly applied to biological cells,

Much like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is able to scan the interior of the human body, the emerging technique of “picosecond ultrasonics,” a type of acoustic imaging, can be used to make virtual slices of biological tissues without destroying them.

Now a team of researchers in Japan and Thailand has shown that picosecond ultrasonics can achieve micron resolution of single cells, imaging their interiors in slices separated by 150 nanometers — in stark contrast to the typical 0.5-millimeter spatial resolution of a standard medical MRI scan. This work is a proof-of-principle that may open the door to new ways of studying the physical properties of living cells by imaging them in vivo.

An April 20, 2015 American Institute of Physics news release, which originated the news item, provides a description of picosecond ultrasonics and more details about the research,

Picosecond ultrasonics has been used for decades as a method to explore the mechanical and thermal properties of materials like metals and semiconductors at submicron scales, and in recent years it has been applied to biological systems as well. The technique is suited for biology because it’s sensitive to sound velocity, density, acoustic impedance and the bulk modulus of cells.

This week, in a story appearing on the cover of the journal Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing, researchers from Walailak University in Thailand and Hokkaido University in Japan describe the first known demonstration of 3-D cell imaging using picosecond ultrasonics.

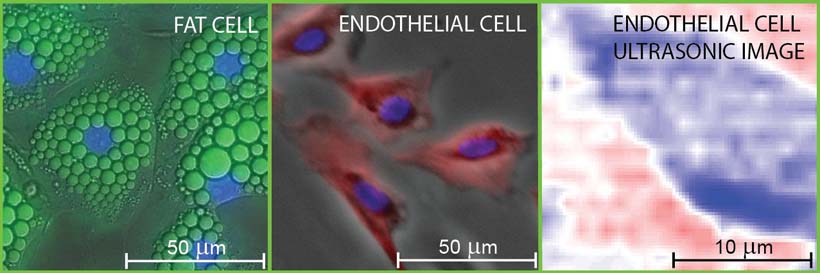

Their work centers on imaging two types of mammalian biological tissue — a bovine aortic endothelial cell, a type of cell that lines a cow’s main artery blood vessel, and a mouse “adipose” fat cell. Endothelial cells were chosen because they play a key role in the physiology of blood cells and are useful in the study of biomechanics. Fat cells, on the other hand, were studied to provide an interesting comparison with varying cell geometries and contents.

How the Work was Done

The team accomplished the imaging by first placing a cell in solution on a titanium-coated sapphire substrate and then scanning a point source of high-frequency sound generated by using a beam of focused ultrashort laser pulses over the titanium film. This was followed by focusing another beam of laser pulses on the same point to pick up tiny changes in optical reflectance caused by the sound traveling through the cell tissue.

“By scanning both beams together, we’re able to build up an acoustic image of the cell that represents one slice of it,” explained co-author Professor Oliver B. Wright, who teaches in the Division of Applied Physics, Faculty of Engineering at Hokkaido University. “We can view a selected slice of the cell at a given depth by changing the timing between the two beams of laser pulses.”

The team’s work is particularly noteworthy because “in spite of much work imaging cells with more conventional acoustic microscopes, the time required for 3-D imaging probably remains too long to be practical,” Wright said. “Building up a 3-D acoustic image, in principle, allows you to see the 3-D relative positions of cell organelles without killing the cell. In our experiments in vitro, while we haven’t yet resolved the cell contents — possibly because cell nuclei weren’t contained within the slices we viewed — it should be possible in the future with various improvements to the technique.”

Fluorescence micrographs of fat and endothelial cells superimposed on differential-interference and phase-contrast images, respectively. The nuclei are stained blue in the micrographs. The image on the right is a picosecond-ultrasonic image of a single endothelial cell with approximately 1-micron lateral and 150-nanometer depth resolutions. Deep blue corresponds to the lowest ultrasonic amplitude.

CREDIT: O. Wright/Hokkaido UniversitySo far, the team has used infrared light to generate sound waves within the cell, “limiting the lateral spatial resolution to about one micron,” Wright explains. “By using an ultraviolet-pulsed laser, we could improve the lateral resolution by about a factor of three — and greatly improve the image quality. And, switching to a diamond substrate instead of sapphire would allow better heat conduction away from the probed area, which, in turn, would enable us to increase the laser power and image quality.”

So lowering the laser power or using substrates with higher thermal conductivity may soon open the door to in vivo imaging, which would be invaluable for investigating the mechanical properties of cell organelles within both vegetal and animal cells.

What’s next for the team? “The method we use to image the cells now actually involves a combination of optical and elastic parameters of the cell, which can’t be easily distinguished,” Wright said. “But we’ve thought of a way to separate them, which will allow us to measure the cell mechanical properties more accurately. So we’ll try this method in the near future, and we’d also like to try our method on single-celled organisms or even bacteria.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Three-dimensional imaging of biological cells with picosecond ultrasonics by Sorasak Danworaphong, Motonobu Tomoda, Yuki Matsumoto, Osamu Matsuda, Toshiro Ohashi, Hiromu Watanabe, Masafumi Nagayama, Kazutoshi Gohara, Paul H. Otsuka, and Oliver B. Wright. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 163701 (2015); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4918275

This paper is open access.

This research reminded me of a data sonification project that I featured in a Feb. 7, 2014 post which includes an embedded sound file of symphonic music based on data from NASA’s (US National Aeronautics and Space Administration) Voyager spacecraft.