A toy that’s been a plaything for 5,000 years and known as a whirligig (in English, anyway) has inspired a scientific tool for use by field biologists and students interested in creating state-of-the-art experiments. Exciting stuff, eh?

A May 23, 2019 Georgia Tech (Georgia Institute of Technology) news release (also on EurekAlert but published on May 22, 2019) announces this development in ‘frugal science’,

A 5,000-year-old toy still enjoyed by kids today has inspired an inexpensive, hand-powered scientific tool that could not only impact how field biologists conduct their research but also allow high-school students and others with limited resources to realize their own state-of-the-art experiments.

The device, a portable centrifuge for preparing scientific samples including DNA, is reported May 21 [2019] in the journal PLOS Biology. The co-first author of the paper is Gaurav Byagathvalli, a senior at Lambert High School in Georgia. His colleagues are M. Saad Bhamla, an assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology; Soham Sinha, a Georgia Tech undergraduate; Janet Standeven, Byagathvalli’s biology teacher at Lambert; and Aaron F. Pomerantz, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I am exceptionally proud of this paper and will remember it 10, 20, 30 years from now because of the uniquely diverse team we put together,” said Bhamla, who is an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

From a Rainforest to a High School

Together the team demonstrated the device, dubbed the 3D-Fuge because it is created through 3D printing, in two separate applications. In a rainforest in Peru the 3D-Fuge was an integral part of a “lab in a backpack” used to identify four previously-unknown plants and insects by sequencing their DNA [deoxyribonucleic acid]. Back in the United States, a slightly different design enabled a new approach to creating living bacterial sensors for the potential detection of disease. That work was conducted at Lambert High School for a synthetic biology competition.

Thanks to social media and a preprint of the PLOS Biology paper on BioRxiv, the 3D-Fuge has already generated interest from around the world, including emails from high-school teachers in Zambia and Kenya. “It’s awesome to see research not just remain isolated to one location but see it spread,” said Byagathvalli. “Through this, we’ve realized how much of an impact simple yet effective tools can have, and hope this technology motivates others to continue along the same path and innovate new solutions to global issues.”

To better share the work, the team has posted the 3D-Fuge designs, videos, and photos online available to anyone.

Frugal Science

One focus of Bhamla’s lab at Georgia Tech is the development of tools for frugal science, or real research that just about anyone can afford. The tools behind state-of-the-art science often cost thousands of dollars that make them inaccessible to those without serious resources.

Centrifuges are a good example. A small benchtop unit costs between $3,000 and $5,000; larger units cost many times that. Yet the devices are necessary to produce concentrated amounts of, say, genomic materials like DNA. By rapidly spinning samples, they separate materials of interest from biological debris.

The Bhamla team found that the 3D-Fuge works as well as its more expensive cousins, but costs less than $1.

An Ancient Toy

The 3D-Fuge is based on earlier work by Bhamla and colleagues at Stanford University on a simple centrifuge made of paper. The “paperfuge,” in turn, was inspired by a toy composed of string and a button that Bhamla played with as a child. He later discovered that these toys, known as whirligigs, have existed for some 5,000 years.

They consist of a disk – like a button – with two holes, through which is threaded a length of flexible cord whose ends are knotted to create a single loop with the disk in the middle. That simple contraption is then swung with two hands until the button is spinning and whirring at very fast speeds.

The earlier paperfuge uses a disk of paper. To that disk Bhamla glued small plastic tubes filled with a sample. He and colleagues reported that the device did indeed create high-quality samples.

In late 2017 Bhamla was separately approached by the Lambert High team and Pomerantz to see if the paperfuge could be adapted for the larger samples they needed (the paperfuge is limited to small samples of ~1 microliter—or one drop of blood).

Together they came up with the 3D-Fuge, which includes cavities for tubes that can hold some 100 times more of a sample than the paperfuge. The team developed two equally effective designs: one for field biology (led by Pomerantz) and the other for the high-school’s synthetic biology project (led by Byagathvalli).

Bhamla notes that the 3D-Fuge has some limitations. For example, it can only process a few samples at a time (some applications require thousands of samples). Further, because it’s 10 times heavier than the paperfuge, it can’t reach the same speeds or produce the same forces of that device. That said, it still weighs only 20 grams, slightly less than a AA battery.

“But it works,” said Bhamla. “All you need is an [appropriate] application and some creativity.”

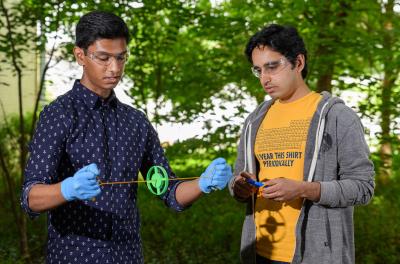

Here are a couple of images showing the 3D-Fuge in action,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A 3D-printed hand-powered centrifuge for molecular biology by Gaurav Byagathvalli, Aaron Pomerantz, Soham Sinha, Janet Standeven, M. Saad Bhamla. PLOS Biology DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000251 Published: May 21, 2019

As always with a Public Library of Science (PLOS) publication, this paper is open access.