A Jan. 29, 2015 news item on Nanowerk provides an overview of the impact quantum chemical reactions may have on nanomedicines. Intriguingly, this line of query started with computations of white dwarf stars,

Quantum chemical calculations have been used to solve big mysteries in space. Soon the same calculations may be used to produce tomorrow’s cancer drugs.

Some years ago research scientists at the University of Oslo in Norway were able to show that the chemical bonding in the magnetic fields of small, compact stars, so-called white dwarf stars, is different from that on Earth. Their calculations pointed to a completely new bonding mechanism between two hydrogen atoms. The news attracted great attention in the media. The discovery, which in fact was made before astrophysicists themselves observed the first hydrogen molecules in white dwarf stars, was made by UiO’s Centre for Theoretical and Computational Chemistry. They based their work on accurate quantum chemical calculations of what happens when atoms and molecules are exposed to extreme conditions.

A Jan. 29, 2015 University of Oslo press release by Yngve Vogt, which originated the news item, offers a substantive description of molecules, electrons, and more for those of us whose last chemistry class is lost in the mists of time,

The research team is headed by Professor Trygve Helgaker, who for the last thirty years has taken the international lead on the design of a computer system for calculating quantum chemical reactions in molecules.

Quantum chemical calculations are needed to explain what happens to the electrons’ trajectories within a molecule.

Consider what happens when UV radiation sends energy-rich photons into your cells. This increases the energy level of the molecules. The outcome may well be that some of the molecules break up. This is exactly what happens when you sun-bathe.

“The extra energy will affect the behaviour of electrons and can destroy the chemical bonding within the molecule. This can only be explained by quantum chemistry. The quantum chemical models are used to produce a picture of the forces and tensions at play between the atoms and the electrons of a molecule, and of what is required for a molecule to dissociate,” says Trygve Helgaker.

The absurd world of the electrons

The quantum chemical calculations solve the Schrödinger equation for molecules. This equation is fundamental to all chemistry and describes the whereabouts of all electrons within a molecule. But here we need to pay attention, for things are really rather more complicated than that. Your high school physics teacher will have told you that electrons circle the atom. Things are not that simple, though, in the world of quantum physics. Electrons are not only particles, but waves as well. The electrons can be in many places at the same time. It’s impossible to keep track of their position. However, there is hope. Quantum chemical models describe the electrons’ statistical positions. In other words, they can establish the probable location of each electron.

The results of a quantum chemical calculation are often more accurate than what is achievable experimentally.

Among other things, the quantum chemical calculations can be used to predict chemical reactions. This means that the chemists will no longer have to rely on guesstimates in the lab. It is also possible to use quantum chemical calculations in order to understand what happens in experiments.

Enormous calculations

The calculations are very demanding.

“The Schrödinger equation is a highly complicated, partial differential equation, which cannot be accurately solved. Instead, we need to make do with heavy simulations”, says researcher Simen Kvaal.

The computations are so demanding that the scientists use one of the University’s fastest supercomputers.

“We are constantly stretching the boundaries of what is possible. We are restricted by the available machine capacity,” explains Helgaker.

Ten years ago it took two weeks to carry out the calculations for a molecule with 140 atoms. Now it can be done in two minutes.

“That’s 20,000 times faster than ten years ago. The computation process is now running 200 times faster because the computers have been doubling their speed every eighteen months. And the process is a further 100 times faster because the software has been undergoing constant improvement,” says senior engineer Simen Reine.

This year the research group has used 40 million CPU hours, of which twelve million were on the University’s supercomputer, which is fitted with ten thousand parallel processors. This allows ten thousand CPU hours to be over and done with in 60 minutes.

“We will always fill the computer’s free capacity. The higher the computational capacity, the bigger and more reliable the calculations.”

Thanks to ever faster computers, the quantum chemists are able to study ever larger molecules.

Today, it’s routine to carry out a quantum chemical calculation of what happens within a molecule of up to 400 atoms. By using simplified models it is possible to study molecules with several thousand atoms. This does, however, mean that some of the effects within the molecule are not being described in detail.

The researchers are now getting close to a level which enables them to study the quantum mechanics of living cells.

“This is exciting. The molecules of living cells may contain many hundred thousand atoms, but there is no need to describe the entire molecule using quantum mechanical principles. Consequently, we are already at a stage when we can help solve biological problems.”

There’s more from the press release which describes how this work could be applied in the future,

Hunting for the electrons of the insulin molecule

The chemists are thus able to combine sophisticated models with simpler ones. “This will always be a matter of what level of precision and detail you require. The optimal approach would have been to use the Schrödinger equation for everything.”

By way of compromise they can give a detailed description of every electron in some parts of the model, while in other parts they are only looking at average numbers.

…

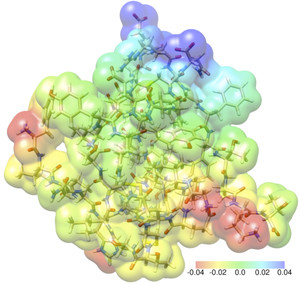

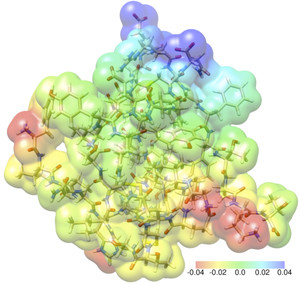

Simen Reine has been using the team’s computer program, while working with Aarhus University [Finland], on a study of the insulin molecule. An insulin molecule consists of 782 atoms and 3,500 electrons.

“All electrons repel each other, while at the same time being pulled towards the atomic nuclei. The nuclei also repel each other. Nevertheless, the molecule remains stable. In order to study a molecule to a high level of precision, we therefore need to consider how all of the electrons move relative to one another. Such calculations are referred to as correlated and are very reliable.”

A complete correlated calculation of the insulin molecule takes nearly half a million CPU hours. If they were given the opportunity to run the program on the entire University’s supercomputer, the calculations would theoretically take two days.

“In ten years, we’ll be able to make these calculations in two minutes.”

Medically important

…

“Quantum chemical calculations can help describe phenomena at a level that may be difficult to access experimentally, but may also provide support for interpreting and planning experiments. Today, the calculations will be put to best use within the fields of molecular biology and biochemistry,” says Knut Fægri [vice-rector at the University of Oslo].

…

“Quantum chemistry is a fundamental theory which is important for explaining molecular events, which is why it is essential to our understanding of biological systems,” says [Associate Professor] Michele Cascella.

By way of an example, he refers to the analysis of enzymes. Enzymes are molecular catalysts that boost the chemical reactions within our cells.

Cascella also points to nanomedicines, which are drugs tasked with distributing medicine round our bodies in a much more accurate fashion.

“In nanomedicine we need to understand physical phenomena on a nano scale, forming as correct a picture as possible of molecular phenomena. In this context, quantum chemical calculations are important,” explains Michele Cascella.

Proteins and enzymes

Professor K. Kristoffer Andersson at the Department of Biosciences uses the simpler form of quantum chemical calculations to study the details of protein structures and the chemical atomic and electronic functions of enzymes.

“It is important to understand the chemical reaction mechanism, and how enzymes and proteins work. Quantum chemical calculations will teach us more about how proteins go about their tasks, step by step. We can also use the calculations to look at activation energy, i.e. how much energy is required to reach a certain state. It is therefore important to understand the chemical reaction patterns in biological molecules in order to develop new drugs,” says Andersson.

His research will also be useful in the search for cancer drugs. He studies radicals, which may be important to cancer. Among other things, he is looking at the metal ions function in proteins. These are ions with a large number of protons, neutrons and electrons.

Photosynthesis

Professor Einar Uggerud at the Department of Chemistry has uncovered an entirely new form of chemical bonding through sophisticated experiments and quantum chemical calculations.

Working with research fellow Glenn Miller, Professor Uggerud has found an unusually fragile key molecule, in a kite-shaped structure, consisting of magnesium, carbon and oxygen. The molecule may provide a new understanding of photosynthesis. Photosynthesis, which forms the basis for all life, converts CO2 into sugar molecules.

The molecule reacts so fast with water and other molecules that it has only been possible to study in isolation from other molecules, in a vacuum chamber.

“Time will tell whether the molecule really has an important connection with photosynthesis,” says Einar Uggerud.

I’m delighted with this explanation as it corrects my understanding of chemical bonds and helps me to better understand computational chemistry. Thank you University of Oslo and Yngve Vogt.

Finally, here’s a representation of an insulin molecule as understood by quantum computation,

INSULIN: Working with Aarhus University, Simen Reine has calculated the tensions between the electrons and atoms of an insulin molecule. An insulin molecule consists of 782 atoms and 3,500 electrons. Illustration: Simen Reine-UiO