Comparing it to a ‘camera’, even with the quotes, is a bit of a stretch for my taste but I can’t come up with a better comparison. Here’s a video so you can judge for yourself,

Caption: This video repeats three times the graphene camera images of a single beat of an embryonic chicken heart. The images, separated by 5 milliseconds, were measured by a laser bouncing off a graphene sheet lying beneath the heart. The images are about 2 millimeters on a side. Credit: UC Berkeley images by Halleh Balch, Alister McGuire and Jason Horng

A June 16, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily announces the research,

Bay Area [San Francisco, California] scientists have captured the real-time electrical activity of a beating heart, using a sheet of graphene to record an optical image — almost like a video camera — of the faint electric fields generated by the rhythmic firing of the heart’s muscle cells.

A University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley) June 16, 2021 news release (also on EurekAlert) by Robert Sanders, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

The graphene camera represents a new type of sensor useful for studying cells and tissues that generate electrical voltages, including groups of neurons or cardiac muscle cells. To date, electrodes or chemical dyes have been used to measure electrical firing in these cells. But electrodes and dyes measure the voltage at one point only; a graphene sheet measures the voltage continuously over all the tissue it touches.

The development, published online last week in the journal Nano Letters, comes from a collaboration between two teams of quantum physicists at the University of California, Berkeley, and physical chemists at Stanford University.

“Because we are imaging all cells simultaneously onto a camera, we don’t have to scan, and we don’t have just a point measurement. We can image the entire network of cells at the same time,” said Halleh Balch, one of three first authors of the paper and a recent Ph.D. recipient in UC Berkeley’s Department of Physics.

While the graphene sensor works without having to label cells with dyes or tracers, it can easily be combined with standard microscopy to image fluorescently labeled nerve or muscle tissue while simultaneously recording the electrical signals the cells use to communicate.

“The ease with which you can image an entire region of a sample could be especially useful in the study of neural networks that have all sorts of cell types involved,” said another first author of the study, Allister McGuire, who recently received a Ph.D. from Stanford and. “If you have a fluorescently labeled cell system, you might only be targeting a certain type of neuron. Our system would allow you to capture electrical activity in all neurons and their support cells with very high integrity, which could really impact the way that people do these network level studies.”

Graphene is a one-atom thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional hexagonal pattern reminiscent of honeycomb. The 2D structure has captured the interest of physicists for several decades because of its unique electrical properties and robustness and its interesting optical and optoelectronic properties.

“This is maybe the first example where you can use an optical readout of 2D materials to measure biological electrical fields,” said senior author Feng Wang, UC Berkeley professor of physics. “People have used 2D materials to do some sensing with pure electrical readout before, but this is unique in that it works with microscopy so that you can do parallel detection.”

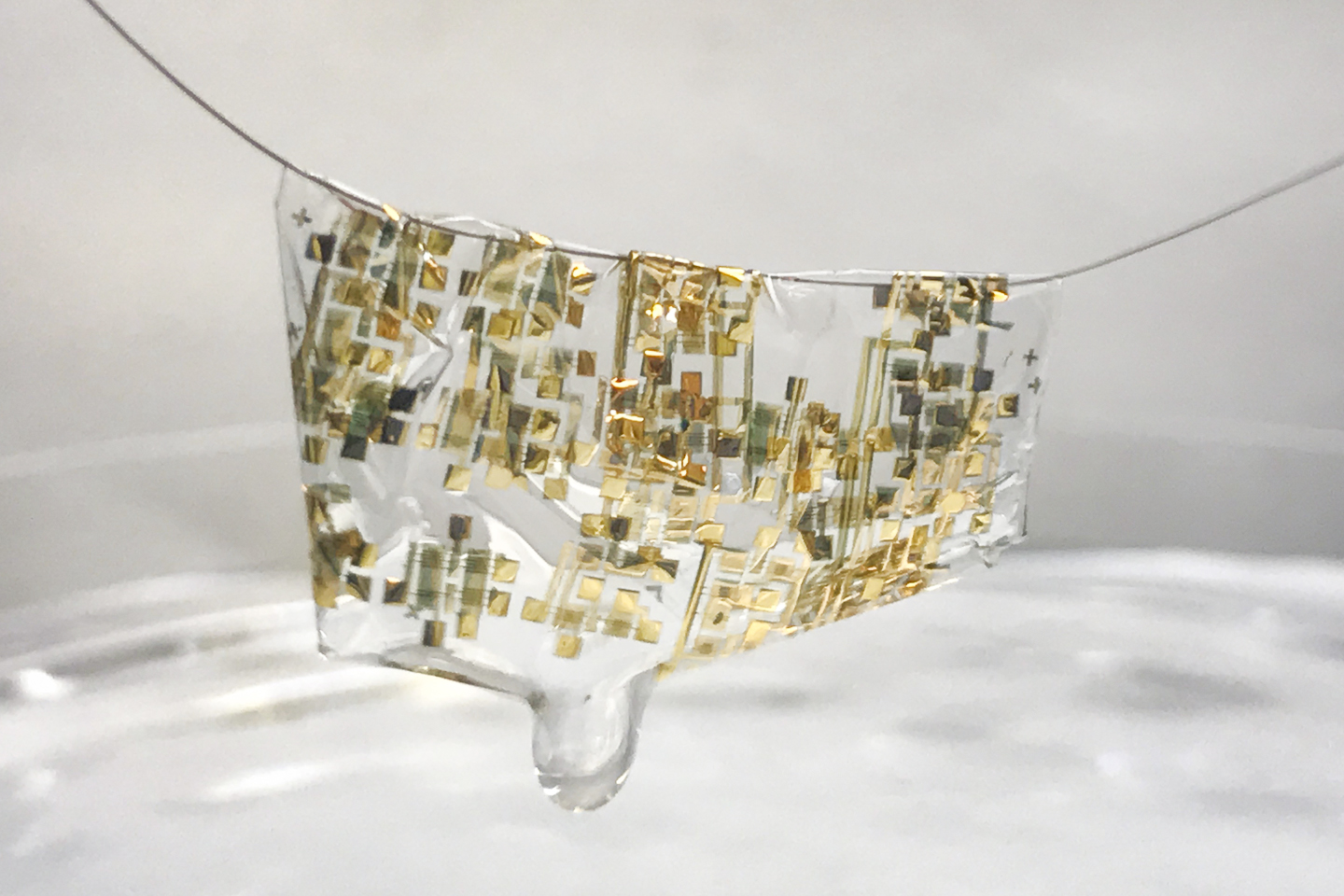

The team calls the tool a critically coupled waveguide-amplified graphene electric field sensor, or CAGE sensor.

“This study is just a preliminary one; we want to showcase to biologists that there is such a tool you can use, and you can do great imaging. It has fast time resolution and great electric field sensitivity,” said the third first author, Jason Horng, a UC Berkeley Ph.D. recipient who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. “Right now, it is just a prototype, but in the future, I think we can improve the device.”

Graphene is sensitive to electric fields

Ten years ago, Wang discovered that an electric field affects how graphene reflects or absorbs light. Balch and Horng exploited this discovery in designing the graphene camera. They obtained a sheet of graphene about 1 centimeter on a side produced by chemical vapor deposition in the lab of UC Berkeley physics professor Michael Crommie and placed on it a live heart from a chicken embryo, freshly extracted from a fertilized egg. These experiments were performed in the Stanford lab of Bianxiao Cui, who develops nanoscale tools to study electrical signaling in neurons and cardiac cells.

The team showed that when the graphene was tuned properly, the electrical signals that flowed along the surface of the heart during a beat were sufficient to change the reflectance of the graphene sheet.

“When cells contract, they fire action potentials that generate a small electric field outside of the cell,” Balch said. “The absorption of graphene right under that cell is modified, so we will see a change in the amount of light that comes back from that position on the large area of graphene.”

In initial studies, however, Horng found that the change in reflectance was too small to detect easily. An electric field reduces the reflectance of graphene by at most 2%; the effect was much less from changes in the electric field when the heart muscle cells fired an action potential.

Together, Balch, Horng and Wang found a way to amplify this signal by adding a thin waveguide below graphene, forcing the reflected laser light to bounce internally about 100 times before escaping. This made the change in reflectance detectable by a normal optical video camera.

“One way of thinking about it is that the more times that light bounces off of graphene as it propagates through this little cavity, the more effects that light feels from graphene’s response, and that allows us to obtain very, very high sensitivity to electric fields and voltages down to microvolts,” Balch said.

The increased amplification necessarily lowers the resolution of the image, but at 10 microns, it is more than enough to study cardiac cells that are several tens of microns across, she said.

Another application, McGuire said, is to test the effect of drug candidates on heart muscle before these drugs go into clinical trials to see whether, for example, they induce an unwanted arrhythmia. To demonstrate this, he and his colleagues observed the beating chicken heart with CAGE and an optical microscope while infusing it with a drug, blebbistatin, that inhibits the muscle protein myosin. They observed the heart stop beating, but CAGE showed that the electrical signals were unaffected.

Because graphene sheets are mechanically tough, they could also be placed directly on the surface of the brain to get a continuous measure of electrical activity — for example, to monitor neuron firing in the brains of those with epilepsy or to study fundamental brain activity. Today’s electrode arrays measure activity at a few hundred points, not continuously over the brain surface.

“One of the things that is amazing to me about this project is that electric fields mediate chemical interactions, mediate biophysical interactions — they mediate all sorts of processes in the natural world — but we never measure them. We measure current, and we measure voltage,” Balch said. “The ability to actually image electric fields gives you a look at a modality that you previously had little insight into.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Graphene Electric Field Sensor Enables Single Shot Label-Free Imaging of Bioelectric Potentials by Halleh B. Balch, Allister F. McGuire, Jason Horng, Hsin-Zon Tsai, Kevin K. Qi, Yi-Shiou Duh, Patrick R. Forrester, Michael F. Crommie, Bianxiao Cui, and Feng Wang. Nano Lett. 2021, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX OI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c00543 Publication Date: June 8, 2021 © 2021 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.