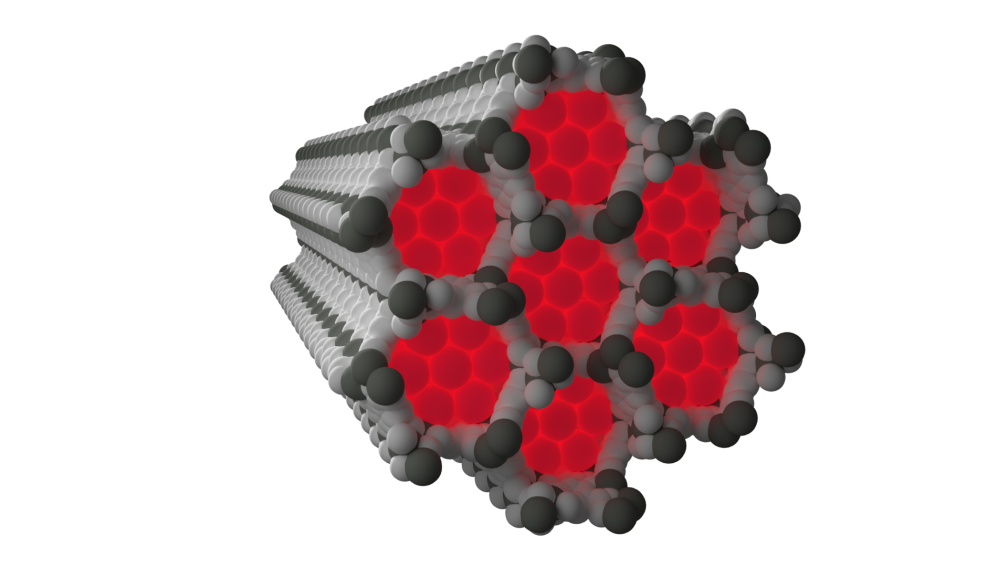

Neon observed experimentally within the pores of NiMOF-74 at 100 K and 100 bar of neon gas pressure Courtesy: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC)

An Aug. 10, 2016 news item on Nanowerk announces the breakthrough (Note: A link has been removed),

In a new study, researchers from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Argonne National Laboratory have teamed up to capture neon within a porous crystalline framework. Neon is well known for being the most unreactive element and is a key component in semiconductor manufacturing, but neon has never been studied within an organic or metal-organic framework until now.

The results (Chemical Communications, “Capturing neon – the first experimental structure of neon trapped within a metal–organic environment”), which include the critical studies carried out at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a DOE Office of Science user facility at Argonne, also point the way towards a more economical and greener industrial process for neon production.

An Aug. 10, 2016 Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) press release, which originated the news item, explains more about neon and about the new process,

Neon is an element that is well-known to the general public due to its iconic use in neon signs, especially in city centres in the United States from the 1920s to the 1960s. In recent years, the industrial use of neon has become dominated by use in excimer lasers to produce semiconductors. Despite being the fifth most abundant element in the atmosphere, the cost of pure neon gas has risen significantly over the years, increasing the demand for better ways to separate and isolate the gas.

During 2015, CCDC scientists presented a talk at the annual American Crystallographic Association (ACA) meeting on the array of elements that have been studied within an organic or metal-organic environment, challenging the crystallographic community to find the next and possibly last element to be added to the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD). A chance encounter at that meeting with Andrey Yakovenko, a beamline scientist at the Advanced Photon Source, resulted in a collaborative project to capture neon – the 95th element to be observed in the CSD.

Neon’s low reactivity, along with the weak scattering of X-rays due to its relatively low number of electrons, means that conclusive experimental observation of neon captured within a crystalline framework is very challenging. In situ high pressure gas flow experiments performed at X-Ray Science Division beamline 17-BM at the APS using the X-ray powder diffraction technique at low temperatures managed to elucidate the structure of two different metal-organic frameworks with neon gas captured within the materials.

“This is a really exciting moment representing the latest new element to be added to the CSD and quite possibly the last given the experimental and safety challenges associated with the other elements yet to be studied” said Peter Wood, Senior Research Scientist at CCDC and lead author on the paper published in Chemical Communications. “More importantly, the structures reported here show the first observation of a genuine interaction between neon and a transition metal, suggesting the potential for future design of selective neon capture frameworks”.

The structure of neon captured within the framework known as NiMOF-74, a porous framework built from nickel metal centres and organic linkers, shows clear nickel to neon interactions forming at low temperatures significantly shorter than would be expected from a typical weak contact.

Andrey Yakovenko said “These fascinating results show the great capabilities of the scientific program at 17-BM and the Advanced Photon Source. Previously we have been doing experiments at our beamline using other much heavier, and therefore easily detectable, noble gases such as xenon and krypton. However, after meeting co-authors Pete, Colin, Amy and Suzanna at the ACA meeting, we decided to perform these much more complicated experiments using the very light and inert gas – neon. In fact, only by using a combination of in situ X-ray powder diffraction measurements, low temperature and high pressure have we been able to conclusively identify the neon atom positions beyond reasonable doubt”.

Summarising the findings, Chris Cahill, Past President of the ACA and Professor of Chemistry, George Washington University said “This is a really elegant piece of in situ crystallography research and it is particularly pleasing to see the collaboration coming about through discussions at an annual ACA meeting”.

The paper describing this study is published in the journal Chemical Communications, http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C6CC04808K. All of the crystal structures reported in the paper are available from the CCDC website: http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures?doi=10.1039/C6CC04808K.

Here’s another link to the paper but this time with a citation for the paper,

Capturing neon – the first experimental structure of neon trapped within a metal–organic environment by

Peter A. Wood, Amy A. Sarjeant, Andrey A. Yakovenko, Suzanna C. Ward, and Colin R. Groom. Chem. Commun., 2016,52, 10048-10051 DOI: 10.1039/C6CC04808K First published online 19 Jul 2016

The paper is open access but you need a free Royal Society of Chemistry publishing personal account to access it.