A May 4, 2019 news item on ScienceDaily announces the latest advance made by Stanford University and Sandia National Laboratories in the field of neuromorphic (brainlike) computing,

The brain’s capacity for simultaneously learning and memorizing large amounts of information while requiring little energy has inspired an entire field to pursue brain-like — or neuromorphic — computers. Researchers at Stanford University and Sandia National Laboratories previously developed one portion of such a computer: a device that acts as an artificial synapse, mimicking the way neurons communicate in the brain.

In a paper published online by the journal Science on April 25 [2019], the team reports that a prototype array of nine of these devices performed even better than expected in processing speed, energy efficiency, reproducibility and durability.

Looking forward, the team members want to combine their artificial synapse with traditional electronics, which they hope could be a step toward supporting artificially intelligent learning on small devices.

“If you have a memory system that can learn with the energy efficiency and speed that we’ve presented, then you can put that in a smartphone or laptop,” said Scott Keene, co-author of the paper and a graduate student in the lab of Alberto Salleo, professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford who is co-senior author. “That would open up access to the ability to train our own networks and solve problems locally on our own devices without relying on data transfer to do so.”

…

An April 25, 2019 Stanford University news release (also on EurekAlert but published May 3, 2019) by Taylor Kubota, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

A bad battery, a good synapse

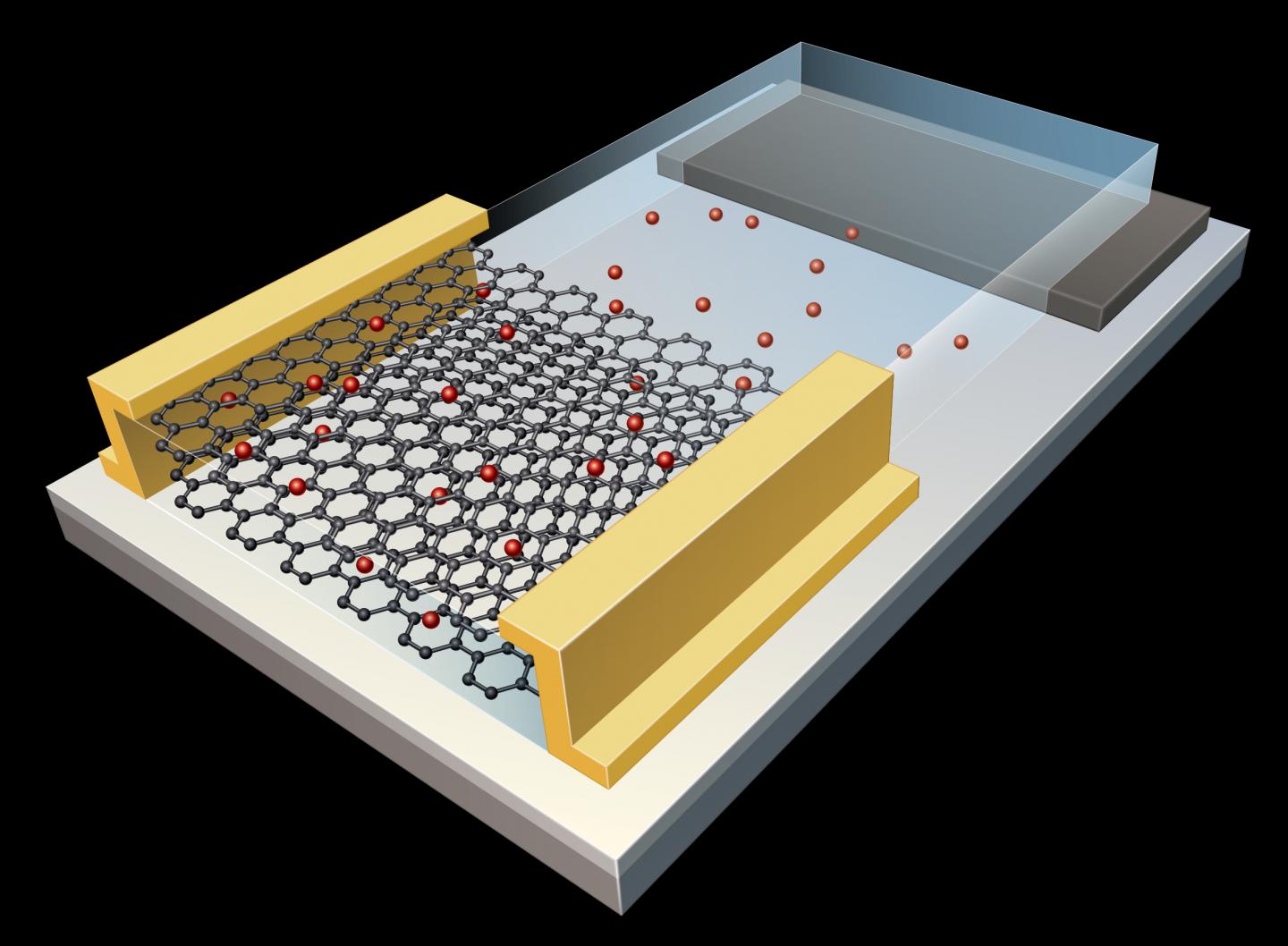

The team’s artificial synapse is similar to a battery, modified so that the researchers can dial up or down the flow of electricity between the two terminals. That flow of electricity emulates how learning is wired in the brain. This is an especially efficient design because data processing and memory storage happen in one action, rather than a more traditional computer system where the data is processed first and then later moved to storage.

Seeing how these devices perform in an array is a crucial step because it allows the researchers to program several artificial synapses simultaneously. This is far less time consuming than having to program each synapse one-by-one and is comparable to how the brain actually works.

In previous tests of an earlier version of this device, the researchers found their processing and memory action requires about one-tenth as much energy as a state-of-the-art computing system needs in order to carry out specific tasks. Still, the researchers worried that the sum of all these devices working together in larger arrays could risk drawing too much power. So, they retooled each device to conduct less electrical current – making them much worse batteries but making the array even more energy efficient.

The 3-by-3 array relied on a second type of device – developed by Joshua Yang at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who is co-author of the paper – that acts as a switch for programming synapses within the array.

“Wiring everything up took a lot of troubleshooting and a lot of wires. We had to ensure all of the array components were working in concert,” said Armantas Melianas, a postdoctoral scholar in the Salleo lab. “But when we saw everything light up, it was like a Christmas tree. That was the most exciting moment.”

During testing, the array outperformed the researchers’ expectations. It performed with such speed that the team predicts the next version of these devices will need to be tested with special high-speed electronics. After measuring high energy efficiency in the 3-by-3 array, the researchers ran computer simulations of a larger 1024-by-1024 synapse array and estimated that it could be powered by the same batteries currently used in smartphones or small drones. The researchers were also able to switch the devices over a billion times – another testament to its speed – without seeing any degradation in its behavior.

“It turns out that polymer devices, if you treat them well, can be as resilient as traditional counterparts made of silicon. That was maybe the most surprising aspect from my point of view,” Salleo said. “For me, it changes how I think about these polymer devices in terms of reliability and how we might be able to use them.”

Room for creativity

The researchers haven’t yet submitted their array to tests that determine how well it learns but that is something they plan to study. The team also wants to see how their device weathers different conditions – such as high temperatures – and to work on integrating it with electronics. There are also many fundamental questions left to answer that could help the researchers understand exactly why their device performs so well.

“We hope that more people will start working on this type of device because there are not many groups focusing on this particular architecture, but we think it’s very promising,” Melianas said. “There’s still a lot of room for improvement and creativity. We only barely touched the surface.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Parallel programming of an ionic floating-gate memory array for scalable neuromorphic computing by Elliot J. Fuller, Scott T. Keene, Armantas Melianas, Zhongrui Wang, Sapan Agarwal, Yiyang Li, Yaakov Tuchman, Conrad D. James, Matthew J. Marinella, J. Joshua Yang3, Alberto Salleo, A. Alec Talin1. Science 25 Apr 2019: eaaw5581 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw5581

This paper is behind a paywall.

For anyone interested in more about brainlike/brain-like/neuromorphic computing/neuromorphic engineering/memristors, use any or all of those terms in this blog’s search engine.