So far, it looks like they’ve managed a single robotic finger. I expect it will take a great deal more work before an entire robotic hand is covered in living skin. BTW, I have a few comments at the end of this post.

I have two news releases highlighting the work. This a June 9, 2022 Cell Press news release,

From action heroes to villainous assassins, biohybrid robots made of both living and artificial materials have been at the center of many sci-fi fantasies, inspiring today’s robotic innovations. It’s still a long way until human-like robots walk among us in our daily lives, but scientists from Japan are bringing us one step closer by crafting living human skin on robots. The method developed, presented June 9 in the journal Matter, not only gave a robotic finger skin-like texture, but also water-repellent and self-healing functions.

“The finger looks slightly ‘sweaty’ straight out of the culture medium,” says first author Shoji Takeuchi, a professor at the University of Tokyo, Japan. “Since the finger is driven by an electric motor, it is also interesting to hear the clicking sounds of the motor in harmony with a finger that looks just like a real one.”

Looking “real” like a human is one of the top priorities for humanoid robots that are often tasked to interact with humans in healthcare and service industries. A human-like appearance can improve communication efficiency and evoke likability. While current silicone skin made for robots can mimic human appearance, it falls short when it comes to delicate textures like wrinkles and lacks skin-specific functions. Attempts at fabricating living skin sheets to cover robots have also had limited success, since it’s challenging to conform them to dynamic objects with uneven surfaces.

“With that method, you have to have the hands of a skilled artisan who can cut and tailor the skin sheets,” says Takeuchi. “To efficiently cover surfaces with skin cells, we established a tissue molding method to directly mold skin tissue around the robot, which resulted in a seamless skin coverage on a robotic finger.”

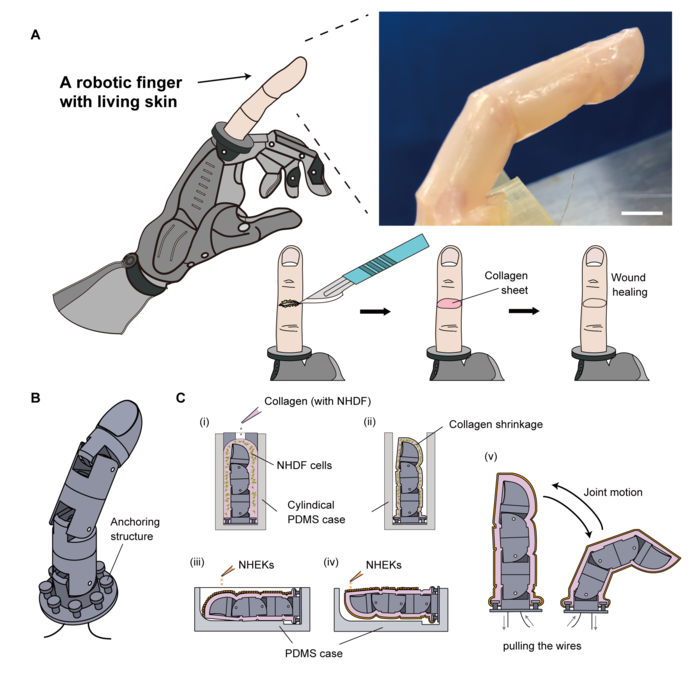

To craft the skin, the team first submerged the robotic finger in a cylinder filled with a solution of collagen and human dermal fibroblasts, the two main components that make up the skin’s connective tissues. Takeuchi says the study’s success lies within the natural shrinking tendency of this collagen and fibroblast mixture, which shrank and tightly conformed to the finger. Like paint primers, this layer provided a uniform foundation for the next coat of cells—human epidermal keratinocytes—to stick to. These cells make up 90% of the outermost layer of skin, giving the robot a skin-like texture and moisture-retaining barrier properties.

The crafted skin had enough strength and elasticity to bear the dynamic movements as the robotic finger curled and stretched. The outermost layer was thick enough to be lifted with tweezers and repelled water, which provides various advantages in performing specific tasks like handling electrostatically charged tiny polystyrene foam, a material often used in packaging. When wounded, the crafted skin could even self-heal like humans’ with the help of a collagen bandage, which gradually morphed into the skin and withstood repeated joint movements.

“We are surprised by how well the skin tissue conforms to the robot’s surface,” says Takeuchi. “But this work is just the first step toward creating robots covered with living skin.” The developed skin is much weaker than natural skin and can’t survive long without constant nutrient supply and waste removal. Next, Takeuchi and his team plan to address those issues and incorporate more sophisticated functional structures within the skin, such as sensory neurons, hair follicles, nails, and sweat glands.

“I think living skin is the ultimate solution to give robots the look and touch of living creatures since it is exactly the same material that covers animal bodies,” says Takeuchi.

A June 10, 2022 University of Tokyo news release (also on EurekAlert but published June 9, 2022) covers some of the same ground while providing more technical details,

Researchers from the University of Tokyo pool knowledge of robotics and tissue culturing to create a controllable robotic finger covered with living skin tissue. The robotic digit had living cells and supporting organic material grown on top of it for ideal shaping and strength. As the skin is soft and can even heal itself, so could be useful in applications that require a gentle touch but also robustness. The team aims to add other kinds of cells into future iterations, giving devices the ability to sense as we do.

Professor Shoji Takeuchi is a pioneer in the field of biohybrid robots, the intersection of robotics and bioengineering. Together with researchers from around the University of Tokyo, he explores things such as artificial muscles, synthetic odor receptors, lab-grown meat, and more. His most recent creation is both inspired by and aims to aid medical research on skin damage such as deep wounds and burns, as well as help advance manufacturing.

“We have created a working robotic finger that articulates just as ours does, and is covered by a kind of artificial skin that can heal itself,” said Takeuchi. “Our skin model is a complex three-dimensional matrix that is grown in situ on the finger itself. It is not grown separately then cut to size and adhered to the device; our method provides a more complete covering and is more strongly anchored too.”

Three-dimensional skin models have been used for some time for cosmetic and drug research and testing, but this is the first time such materials have been used on a working robot. In this case, the synthetic skin is made from a lightweight collagen matrix known as a hydrogel, within which several kinds of living skin cells called fibroblasts and keratinocytes are grown. The skin is grown directly on the robotic component which proved to be one of the more challenging aspects of this research, requiring specially engineered structures that can anchor the collagen matrix to them, but it was worth it for the aforementioned benefits.

“Our creation is not only soft like real skin but can repair itself if cut or damaged in some way. So we imagine it could be useful in industries where in situ repairability is important as are humanlike qualities, such as dexterity and a light touch,” said Takeuchi. “In the future, we will develop more advanced versions by reproducing some of the organs found in skin, such as sensory cells, hair follicles and sweat glands. Also, we would like to try to coat larger structures.”

The main long-term aim for this research is to open up new possibilities in advanced manufacturing industries. Having humanlike manipulators could allow for the automation of things currently only achievable by highly skilled professionals. Other areas such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and regenerative medicine could also benefit. This could potentially reduce cost, time and complexity of research in these areas and could even reduce the need for animal testing.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Living skin on a robot by Michio Kawai, Minghao Nie, Haruka Oda, Yuya Morimoto, Shoji Takeuchi. Matter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2022.05.019 Published:June 09, 2022

This paper appears to be open access.

There more images and there’s at least one video all of which can be found by clicking on the links to one or both of the news releases and to the paper. Personally, I found the images fascinating and …

Frankenstein, cyborgs, and more

The word is creepy. I find the robot finger images fascinating and creepy. The work brings to mind Frankenstein (by Mary Shelley) and The Island of Dr. Moreau (by H. G. Wells) both of which feature cautionary tales. Dr. Frankenstein tries to bring a dead ‘person’ assembled with parts from various corpses to life and Dr. Moreau attempts to create hybrids composed humans and animals. It’s fascinating how 19th century nightmares prefigure some of the research being performed now.

The work also brings to mind the ‘uncanny valley’, a term coined by Masahiro Mori, where people experience discomfort when something that’s not human seems too human. I have an excerpt from an essay that Mori wrote about the uncanny valley in my March 10, 2011 posting; scroll down about 50% of the way.) The diagram which accompanies it illustrates the gap between the least uncanny or the familiar (a healthy person, a puppet, etc.) and the most uncanny or the unfamiliar (a corpse, a zombie, a prosthetic hand).

Mori notes that the uncanny valley is not immovable; things change and the unfamiliar becomes familiar. Presumably, one day, I will no longer find robots with living skin to be creepy.

All of this changes the meaning (for me) of a term i coined for this site, ‘machine/flesh’. At the time, I was thinking of prosthetics and implants and how deeply they are being integrated into the body. But this research reverses the process. Now, the body (skin in this case) is being added to the machine (robot).