It doesn’t sound like these nanosponges are going to help you with your hangover but should you have a snakebite, an E. coli infection or other such pore-forming toxin in your blood, engineers at the University of California at San Diego are working on a solution. From the University of California at San Diego Apr. 14, 2103 news release,

Engineers at the University of California, San Diego have invented a “nanosponge” capable of safely removing a broad class of dangerous toxins from the bloodstream – including toxins produced by MRSA, E. coli, poisonous snakes and bees. These nanosponges, which thus far have been studied in mice, can neutralize “pore-forming toxins,” which destroy cells by poking holes in their cell membranes. Unlike other anti-toxin platforms that need to be custom synthesized for individual toxin type, the nanosponges can absorb different pore-forming toxins regardless of their molecular structures. In a study against alpha-haemolysin toxin from MRSA, pre-innoculation with nanosponges enabled 89 percent of mice to survive lethal doses. Administering nanosponges after the lethal dose led to 44 percent survival.

They’ve produced a video about their work,

I like the fact that this therapy isn’t specific but can be used for different toxins (from the news release),

“This is a new way to remove toxins from the bloodstream,” said Liangfang Zhang, a nanoengineering professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and the senior author on the study. “Instead of creating specific treatments for individual toxins, we are developing a platform that can neutralize toxins caused by a wide range of pathogens, including MRSA and other antibiotic resistant bacteria,” said Zhang. The work could also lead to non-species-specific therapies for venomous snake bites and bee stings, which would make it more likely that health care providers or at-risk individuals will have life-saving treatments available when they need them most.

Here’s how the nanosponges work (from the news release),

In order to evade the immune system and remain in circulation in the bloodstream, the nanosponges are wrapped in red blood cell membranes. This red blood cell cloaking technology was developed in Liangfang Zhang’s lab at UC San Diego. The researchers previously demonstrated that nanoparticles disguised as red blood cells could be used to deliver cancer-fighting drugs directly to a tumor. …

Red blood cells are one of the primary targets of pore-forming toxins. When a group of toxins all puncture the same cell, forming a pore, uncontrolled ions rush in and the cell dies.

The nanosponges look like red blood cells, and therefore serve as red blood cell decoys that collect the toxins. The nanosponges absorb damaging toxins and divert them away from their cellular targets. The nanosponges had a half-life of 40 hours in the researchers’ experiments in mice. Eventually the liver safely metabolized both the nanosponges and the sequestered toxins, with the liver incurring no discernible damage. [emphasis mine]

It’s reassuring to see that this therapy doesn’t damage as it heals.

For those interested, here’s some technical information about how the nanosponges are created in the laboratory (from the news release),

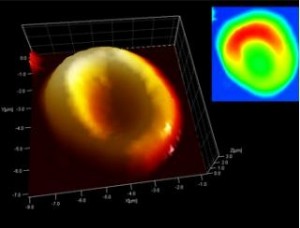

Each nanosponge has a diameter of approximately 85 nanometers and is made of a biocompatible polymer core wrapped in segments of red blood cells membranes.

Zhang’s team separates the red blood cells from a small sample of blood using a centrifuge and then puts the cells into a solution that causes them to swell and burst, releasing hemoglobin and leaving RBC [red blood cell] skins behind. The skins are then mixed with the ball-shaped nanoparticles until they are coated with a red blood cell membrane.

Just one red blood cell membrane can make thousands of nanosponges, which are 3,000 times smaller than a red blood cell. With a single dose, this army of nanosponges floods the bloodstream, outnumbering red blood cells and intercepting toxins. Based on test-tube experiments, the number of toxins each nanosponge could absorb depended on the toxin. For example, approximately 85 alpha-haemolysin toxin produced by MRSA, 30 stretpolysin-O toxins and 850 melittin monomoers, which are part of bee venom.

In mice, administering nanosponges and alpha-haemolysin toxin simultaneously at a toxin-to-nanosponge ratio of 70:1 neutralized the toxins and caused no discernible damage.

This seems like promising work and, hopefully, they will be testing these nanosponges in human clinical trials soon.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the researchers’ paper,

A biomimetic nanosponge that absorbs pore-forming toxins by Che-Ming J. Hu, Ronnie H. Fang, Jonathan Copp, Brian T. Luk,& Liangfang Zhang. Nature Nanotechnology (2013) doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.54 Published online 14 April 2013

This paper is behind a paywall. (H/T to EurekAlert [Apr. 14, 2013 news release].)

The last time I wrote about nanosponges it was in the context of oil spills in my Apr. 17, 2012 posting.