I’ve always been fond of ‘l’ words and so it is that I’m compelled to post a story about a “luciferin-luciferase system” or, in this case, a story about insect bioluminescence.

A September 9, 2020 Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) press release (also on EurekAlert but published Sept. 11, 2020) announces research into ‘blue’ bioluminescence,

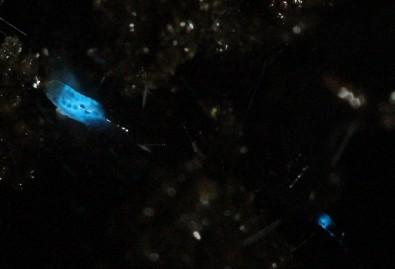

Molecules belonging to an almost unknown bioluminescent system found in larvae of the fungus gnat Orfelia fultoni (subfamily Keroplatinae) have been isolated for the first time by researchers at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The small fly is one of the few terrestrial organisms that produce blue light. It inhabits riverbanks in the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern United States. A key part of its bioluminescent system is a molecule also present in two recently discovered Brazilian flies.

The study, supported by Paulo Research Foundation – FAPESP, is published in Scientific Reports. Five authors are affiliated with UFSCar and two with universities in the United States.

The bioluminescent systems of glow-worms, fireflies and other insects are normally made up of luciferin (a low molecular weight molecule) and luciferase, an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of luciferin by oxygen, producing light. While some bioluminescent systems are well known and even used in biotechnological applications, others are poorly understood, including blue light-emitting systems, such as that of O. fultoni.

“In the published paper, we describe the properties of the insect’s luciferase and luciferin and their anatomical location in its larvae. We also specify several possible proteins that are possible candidates for the luciferase. We don’t yet know what type of protein it is, but it’s likely to be a hexamerin. In insects, hexamerins are storage proteins that provide amino acids, besides having other functions, such as binding low molecular weight compounds, like luciferin,” said Vadim Viviani, a professor in UFSCar’s Sustainability Science and Technology Center (CCTS) in Sorocaba, São Paulo, and principal investigator for the study.

The study was part of the FAPESP-funded project “Arthropod bioluminescence“. The partnership with United States-based researchers dates from a previous project, supported by FAPESP and the United States National Science Foundation (NSF), in partnership with Vanderbilt University (VU), located in Nashville, Tennessee.

In addition to luciferin and luciferase, researchers began characterizing a complex found in insects of the family Keroplatidae, which, in addition to O. fultoni, also includes a Brazilian species in the genus Neoditomyia that produces only luciferin and hence does not emit light.

Because they do not use it to emit light, the luciferin in O. fultoni and the Brazilian Neoditomyia has been named keroplatin. In larvae of this subfamily, keroplatin is associated with “black bodies” – large cells containing dark granules, proteins and probably mitochondria (energy-producing organelles). Researchers are still investigating the biological significance of this association between keroplatin and mitochondria.

“It’s a mystery,” Viviani said. “This luciferin may play a role in the mitochondrial energy metabolism. At night, probably in the presence of a natural chemical reducer, the luciferin is released by these black bodies and reacts with the surrounding luciferase to produce blue light. These are possibilities we plan to study.”

Brazilian cousins

An important factor in the elucidation of the United States insect’s bioluminescent system was the discovery of a larva that lives in Intervales State Park in São Paulo in 2018. It does not emit light but produces luciferin, similar to O. fultoni (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/29066).

In their latest study, the group injected purified luciferase from the United States species into larvae of the Brazilian species, which then produced blue light. The nonluminescent Brazilian species is more abundant in nature than the United States species, so a larger amount of the material could be obtained for study purposes, especially to characterize the luciferin (keroplatin) present in both species.

In 2019, the group discovered and described Neoceroplatus betaryensis, a new species of fungus gnat, in collaboration with Cassius Stevani, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Chemistry (IQ-USP). It was the first blue light-emitting insect found in South America and was detected in a privately held forest reserve near the Upper Ribeira State Tourist Park (PETAR) in the southern portion of the state of São Paulo. A close relative of O. fultoni, N. betaryensis inhabits fallen tree trunks in humid places (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/31797).

“We show that the bioluminescent system of this Brazilian species is identical to that of O. fultoni. However, the insect is very rare, and so it’s hard to obtain sufficient material for research purposes,” Viviani said.

The researchers are now cloning the insect’s luciferase and characterizing it in molecular terms. They are also analyzing the chemical structure of its luciferin and the morphology of its lanterns.

“Once all this has been determined, we’ll be able to synthesize the luciferin and luciferase in the lab and use these systems in a range of biotech applications, such as studying cells. This will help us understand more about human diseases, among other things,” Viviani said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A new brilliantly blue-emitting luciferin-luciferase system from Orfelia fultoni and Keroplatinae (Diptera) by Vadim R. Viviani, Jaqueline R. Silva, Danilo T. Amaral, Vanessa R. Bevilaqua, Fabio C. Abdalla, Bruce R. Branchini & Carl H. Johnson. Scientific Reports volume 10, Article number: 9608 (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66286-1 Published 15 June 2020

This paper is open access.