Preserving a smell? It’s an intriguing idea and forms the research focus for scientists at the University College London’s (UCL) Institute for Sustainable Heritage according to an April 6, 2017 Biomed Central news release on EurekAlert,

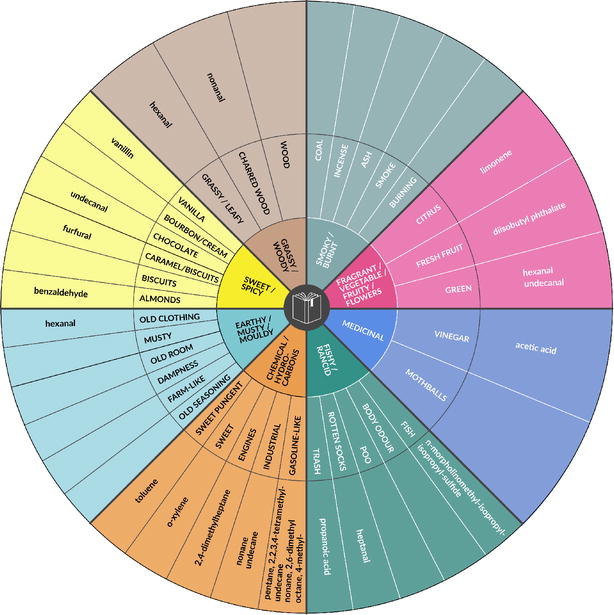

A ‘Historic Book Odour Wheel’ which has been developed to document and archive the aroma associated with old books, is being presented in a study in the open access journal Heritage Science. Researchers at UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage created the wheel as part of an experiment in which they asked visitors to St Paul’s Cathedral’s Dean and Chapter library in London to characterize its smell.

The visitors most frequently described the aroma of the library as ‘woody’ (selected by 100% of the visitors who were asked), followed by ‘smoky’ (86%), ‘earthy'(71%) and ‘vanilla’ (41%). The intensity of the smells was assessed as between ‘strong odor’ and ‘very strong odor’. Over 70% of the visitors described the smell as pleasant, 14% as ‘mildly pleasant’ and 14% as ‘neutral’.

In a separate experiment, the researchers presented visitors to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery with an unlabelled historic book smell – sampled from a 1928 book they obtained from a second-hand bookshop in London – and collected the terms used to describe the smell. The word ‘chocolate’ – or variations such as ‘cocoa’ or ‘chocolatey’ – was used most often, followed by ‘coffee’, ‘old’, ‘wood’ and ‘burnt’. Participants also mentioned smells including ‘fish’, ‘body odour’, ‘rotten socks’ and ‘mothballs’.

Cecilia Bembibre, heritage scientist at UCL and corresponding author of the study said: “Our odour wheel provides an example of how scientists and historians could begin to identify, analyze and document smells that have cultural significance, such as the aroma of old books in historic libraries. The role of smells in how we perceive heritage has not been systematically explored until now.”

Attempting to answer the question of whether certain smells could be considered part of our cultural heritage and if so how they could be identified, protected and conserved, the researchers also conducted a chemical analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) which they sampled from books in the library. VOCs are chemicals that evaporate at low temperatures, many of which can be perceived as scents or odors.

Combining their findings from the VOC analysis with the visitors’ characterizations, the authors created their Historic Book Odour wheel, which shows the chemical description of a smell (such as acetic acid) together with the sensory descriptions provided by the visitors (such as ‘vinegar’).

Cecilia Bembibre said: “By documenting the words used by the visitors to describe a heritage smell, our study opens a discussion about developing a vocabulary to identify aromas that have cultural meaning and significance.”

She added: “The Historic Book Odour Wheel also has the potential to be used as a diagnostic tool by conservators, informing on the condition of an object, for example its state of decay, through its olfactory profile.”

The authors suggest that, in addition to its use for the identification and conservation of smells, the Historic Book Odour Wheel could potentially be used to recreate smells and aid the design of olfactory experiences in museums, allowing visitors to form a personal connection with exhibits by allowing them to understand what the past smelled like.

Before this can be done, further research is needed to build on the preliminary findings in this study to allow them to inform and benefit heritage management, conservation, visitor experience design and heritage policy making.

Here’s what the Historic Book Odour Wheel looks like,

Odour wheel of historic book containing general aroma categories, sensory descriptors and chemical information on the smells as sampled (colours are arbitrary) Courtesy: Heritage Science [downloaded from https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-016-0114-1

Smell of heritage: a framework for the identification, analysis and archival of historic odours by Cecilia Bembibre and Matija Strlič. Heritage Science20175:2 DOI: 10.1186/s40494-016-0114-1 Published: 7 April 2017

© The Author(s) 2017

This paper is open access.