If ‘chisel’ made you think of sculpting, you are correct. The researchers are alluding to the process of sculpting in their research.

From a February 9, 2021 news item on phys.org (Note: Links have been removed),

A holy grail for orthopedic research is a method for not only creating artificial bone tissue that precisely matches the real thing, but does so in such microscopic detail that it includes tiny structures potentially important for stem cell differentiation, which is key to bone regeneration.

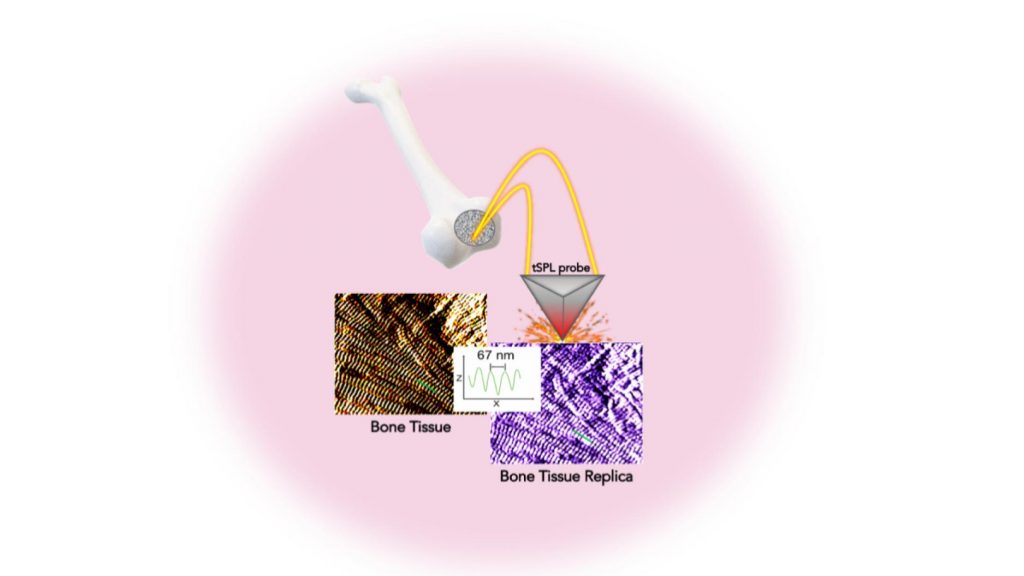

Researchers at the NYU [New York University] Tandon School of Engineering and New York Stem Cell Foundation Research Institute (NYSF) have taken a major step by creating the exact replica of a bone using a system that pairs biothermal imaging with a heated “nano-chisel.” In a study, “Cost and Time Effective Lithography of Reusable Millimeter Size Bone Tissue Replicas with Sub-15 nm Feature Size on a Biocompatible Polymer,” which appears in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, the investigators detail a system allowing them to sculpt, in a biocompatible material, the exact structure of the bone tissue, with features smaller than the size of a single protein—a billion times smaller than a meter. This platform, called, bio-thermal scanning probe lithography (bio-tSPL), takes a “photograph” of the bone tissue, and then uses the photograph to produce a bona-fide replica of it.

The team, led by Elisa Riedo, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NYU Tandon, and Giuseppe Maria de Peppo, a Ralph Lauren Senior Principal Investigator at the NYSF, demonstrated that it is possible to scale up bio-tSPL to produce bone replicas on a size meaningful for biomedical studies and applications, at an affordable cost. These bone replicas support the growth of bone cells derived from a patient’s own stem cells, creating the possibility of pioneering new stem cell applications with broad research and therapeutic potential. This technology could revolutionize drug discovery and result in the development of better orthopedic implants and devices.

…

A February 8, 2021 NYU Tandon School of Engineering news release (also on EurekAlert but published February 9, 2021), which originated the news item, explains the work in further detail,

In the human body, cells live in specific environments that control their behavior and support tissue regeneration via provision of morphological and chemical signals at the molecular scale. In particular, bone stem cells are embedded in a matrix of fibers — aggregates of collagen molecules, bone proteins, and minerals. The bone hierarchical structure consists of an assembly of micro- and nano- structures, whose complexity has hindered their replication by standard fabrication methods so far.

“tSPL is a powerful nanofabrication method that my lab pioneered a few years ago, and it is at present implemented by using a commercially available instrument, the NanoFrazor,” said Riedo. “However, until today, limitations in terms of throughput and biocompatibility of the materials have prevented its use in biological research. We are very excited to have broken these barriers and to have led tSPL into the realm of biomedical applications.”

Its time- and cost-effectiveness, as well as the cell compatibility and reusability of the bone replicas, make bio-tSPL an affordable platform for the production of surfaces that perfectly reproduce any biological tissue with unprecedented precision.

“I am excited about the precision achieved using bio-tSPL. Bone-mimetic surfaces, such as the one reproduced in this study, create unique possibilities for understanding cell biology and modeling bone diseases, and for developing more advanced drug screening platforms,” said de Peppo. “As a tissue engineer, I am especially excited that this new platform could also help us create more effective orthopedic implants to treat skeletal and maxillofacial defects resulting from injury or disease.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Cost and Time Effective Lithography of Reusable Millimeter Size Bone Tissue Replicas With Sub‐15 nm Feature Size on A Biocompatible Polymer by Xiangyu Liu, Alessandra Zanut, Martina Sladkova‐Faure, Liyuan Xie, Marcus Weck, Xiaorui Zheng, Elisa Riedo, Giuseppe Maria de Peppo. Advanced Functional Materials DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202008662 First published: 05 February 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.