Years ago I was asked about carbon sequestration and nanotechnology and could not come up with any examples. At last I have something for the next time the question is asked. From a June 11, 2019 news item on ScienceDaily,

University of Colorado Boulder researchers have developed nanobio-hybrid organisms capable of using airborne carbon dioxide and nitrogen to produce a variety of plastics and fuels, a promising first step toward low-cost carbon sequestration and eco-friendly manufacturing for chemicals.

By using light-activated quantum dots to fire particular enzymes within microbial cells, the researchers were able to create “living factories” that eat harmful CO2 and convert it into useful products such as biodegradable plastic, gasoline, ammonia and biodiesel.

…

A June 11, 2019 University of Colorado at Boulder news release (also on EurekAlert) by Trent Knoss, which originated the news item, provides a deeper dive into the research,

“The innovation is a testament to the power of biochemical processes,” said Prashant Nagpal, lead author of the research and an assistant professor in CU Boulder’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering. “We’re looking at a technique that could improve CO2 capture to combat climate change and one day even potentially replace carbon-intensive manufacturing for plastics and fuels.”

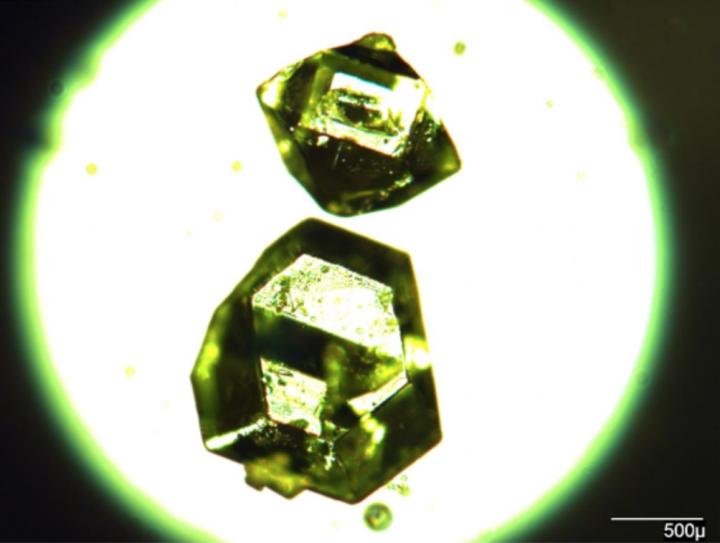

The project began in 2013, when Nagpal and his colleagues began exploring the broad potential of nanoscopic quantum dots, which are tiny semiconductors similar to those used in television sets. Quantum dots can be injected into cells passively and are designed to attach and self-assemble to desired enzymes and then activate these enzymes on command using specific wavelengths of light.

Nagpal wanted to see if quantum dots could act as a spark plug to fire particular enzymes within microbial cells that have the means to convert airborne CO2 and nitrogen, but do not do so naturally due to a lack of photosynthesis.

By diffusing the specially-tailored dots into the cells of common microbial species found in soil, Nagpal and his colleagues bridged the gap. Now, exposure to even small amounts of indirect sunlight would activate the microbes’ CO2 appetite, without a need for any source of energy or food to carry out the energy-intensive biochemical conversions.

“Each cell is making millions of these chemicals and we showed they could exceed their natural yield by close to 200 percent,” Nagpal said.

The microbes, which lie dormant in water, release their resulting product to the surface, where it can be skimmed off and harvested for manufacturing. Different combinations of dots and light produce different products: Green wavelengths cause the bacteria to consume nitrogen and produce ammonia while redder wavelengths make the microbes feast on CO2 to produce plastic instead.

The process also shows promising signs of being able to operate at scale. The study found that even when the microbial factories were activated consistently for hours at a time, they showed few signs of exhaustion or depletion, indicating that the cells can regenerate and thus limit the need for rotation.

“We were very surprised that it worked as elegantly as it did,” Nagpal said. “We’re just getting started with the synthetic applications.”

The ideal futuristic scenario, Nagpal said, would be to have single-family homes and businesses pipe their CO2 emissions directly to a nearby holding pond, where microbes would convert them to a bioplastic. The owners would be able to sell the resulting product for a small profit while essentially offsetting their own carbon footprint.

“Even if the margins are low and it can’t compete with petrochemicals on a pure cost basis, there is still societal benefit to doing this,” Nagpal said. “If we could convert even a small fraction of local ditch ponds, it would have a sizeable impact on the carbon output of towns. It wouldn’t be asking much for people to implement. Many already make beer at home, for example, and this is no more complicated.”

The focus now, he said, will shift to optimizing the conversion process and bringing on new undergraduate students. Nagpal is looking to convert the project into an undergraduate lab experiment in the fall semester, funded by a CU Boulder Engineering Excellence Fund grant. Nagpal credits his current students with sticking with the project over the course of many years.

“It has been a long journey and their work has been invaluable,” he said. “I think these results show that it was worth it.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanorg Microbial Factories: Light-Driven Renewable Biochemical Synthesis Using Quantum Dot-Bacteria Nanobiohybrids by Yuchen Ding, John R. Bertram, Carrie Eckert, Rajesh Reddy Bommareddy, Rajan Patel, Alex Conradie, Samantha Bryan, Prashant Nagpal. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2019XXXXXXXXXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b02549 Publication Date:June 7, 2019

Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.