Researchers claim their lab-made cartilage is better than the real thing in an August 11, 2022 news item on phys.org, Note: Links have been removed,

Over-the-counter pain relievers, physical therapy, steroid injections—some people have tried it all and are still dealing with knee pain.

Often knee pain comes from the progressive wear and tear of cartilage known as osteoarthritis, which affects nearly one in six adults—867 million people—worldwide. For those who want to avoid replacing the entire knee joint, there may soon be another option that could help patients get back on their feet fast, pain-free, and stay that way.

Writing in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, a Duke University-led team says they have created the first gel-based cartilage substitute that is even stronger and more durable than the real thing.

…

Here’s the August 11, 2022 Duke University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, where you’ll find more details about the research, Note: Links have been removed,

Mechanical testing reveals that the Duke team’s hydrogel — a material made of water-absorbing polymers — can be pressed and pulled with more force than natural cartilage, and is three times more resistant to wear and tear.

Implants made of the material are currently being developed by Sparta Biomedical and tested in sheep. Researchers are gearing up to begin clinical trials in humans next year.

“If everything goes according to plan, the clinical trial should start as soon as April 2023,” said Duke chemistry professor Benjamin Wiley, who led the research along with Duke mechanical engineering and materials science professor Ken Gall.

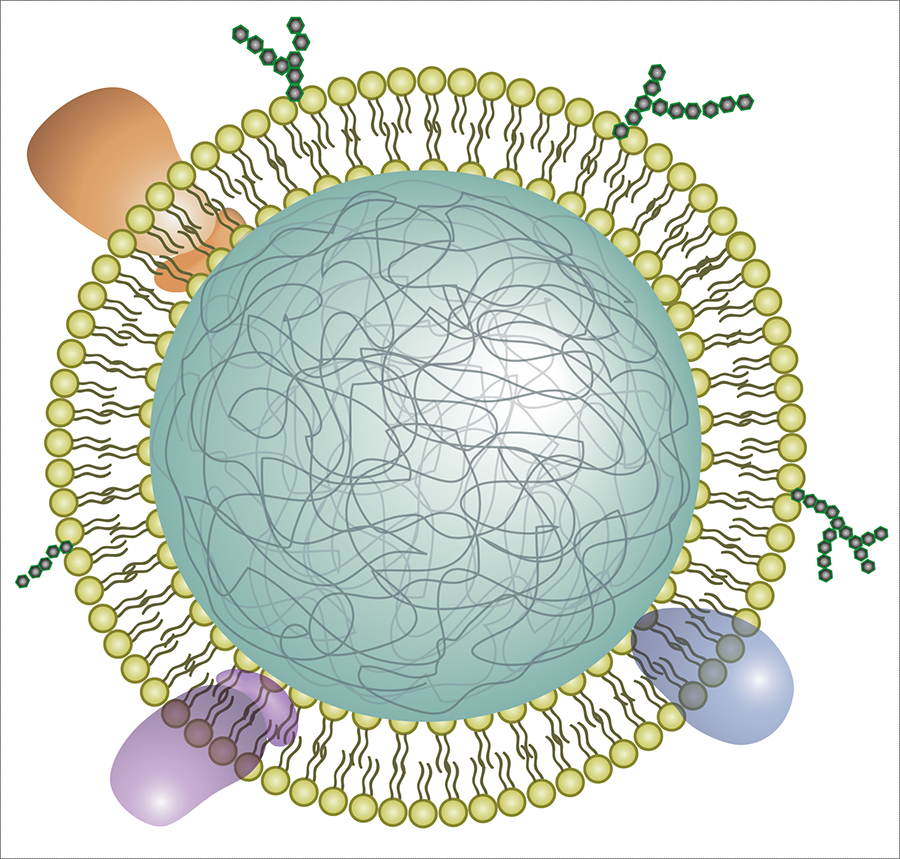

To make this material, the Duke team took thin sheets of cellulose fibers and infused them with a polymer called polyvinyl alcohol — a viscous goo consisting of stringy chains of repeating molecules — to form a gel.

The cellulose fibers act like the collagen fibers in natural cartilage, Wiley said — they give the gel strength when stretched. The polyvinyl alcohol helps it return to its original shape. The result is a Jello-like material, 60% water, which is supple yet surprisingly strong.

Natural cartilage can withstand a whopping 5,800 to 8,500 pounds per inch of tugging and squishing, respectively, before reaching its breaking point. Their lab-made version is the first hydrogel that can handle even more. It is 26% stronger than natural cartilage in tension, something like suspending seven grand pianos from a key ring, and 66% stronger in compression — which would be like parking a car on a postage stamp.

“It’s really off the charts in terms of hydrogel strength,” Wiley said.

The team has already made hydrogels with remarkable properties. In 2020, they reported that they had created the first hydrogel strong enough for knees, which feel the force of two to three times body weight with each step.

Putting the gel to practical use as a cartilage replacement, however, presented additional design challenges. One was achieving the upper limits of cartilage’s strength. Activities like hopping, lunging, or climbing stairs put some 10 Megapascals of pressure on the cartilage in the knee, or about 1,400 pounds per square inch. But the tissue can take up to four times that before it breaks.

“We knew there was room for improvement,” Wiley said.

In the past, researchers attempting to create stronger hydrogels used a freeze-thaw process to produce crystals within the gel, which drive out water and help hold the polymer chains together. In the new study, instead of freezing and thawing the hydrogel, the researchers used a heat treatment called annealing to coax even more crystals to form within the polymer network.

By increasing the crystal content, the researchers were able to produce a gel that can withstand five times as much stress from pulling and nearly twice as much squeezing relative to freeze-thaw methods.

The improved strength of the annealed gel also helped solve a second design challenge: securing it to the joint and getting it to stay put.

Cartilage forms a thin layer that covers the ends of bones so they don’t grind against one another. Previous studies haven’t been able to attach hydrogels directly to bone or cartilage with sufficient strength to keep them from breaking loose or sliding off. So the Duke team came up with a different approach.

Their method of attachment involves cementing and clamping the hydrogel to a titanium base. This is then pressed and anchored into a hole where the damaged cartilage used to be. Tests show the design stays fastened 68% more firmly than natural cartilage on bone.

“Another concern for knee implants is wear over time, both of the implant itself and the opposing cartilage,” Wiley said.

Other researchers have tried replacing damaged cartilage with knee implants made of metal or polyethylene, but because these materials are stiffer than cartilage they can chafe against other parts of the knee.

In wear tests, the researchers took artificial cartilage and natural cartilage and spun them against each other a million times, with a pressure similar to what the knee experiences during walking. Using a high-resolution X-ray scanning technique called micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), the scientists found that the surface of their lab-made version held up three times better than the real thing. Yet because the hydrogel mimics the smooth, slippery, cushiony nature of real cartilage, it protects other joint surfaces from friction as they slide against the implant.

Natural cartilage is remarkably durable stuff. But once damaged, it has limited ability to heal because it doesn’t have any blood vessels, Wiley said.

In the United States, osteoarthritis is twice as common today than it was a century ago. Surgery is an option when conservative treatments fail. Over the decades surgeons have developed a number of minimally invasive approaches, such as removing loose cartilage, or making holes to stimulate new growth, or transplanting healthy cartilage from a donor. But all of these methods require months of rehab, and some percentage of them fail over time.

Generally considered a last resort, total knee replacement is a proven way to relieve pain. But artificial joints don’t last forever, either. Particularly for younger patients who want to avoid major surgery for a device that will only need to be replaced again down the line, Wiley said, “there’s just not very good options out there.”

“I think this will be a dramatic change in treatment for people at this stage,” Wiley said.

This work was supported in part by Sparta Biomedical and by the Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility at Duke University. Wiley and Gall are shareholders in Sparta Biomedical.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Synthetic Hydrogel Composite with a Strength and Wear Resistance Greater than Cartilage by Jiacheng Zhao, Huayu Tong, Alina Kirillova, William J. Koshut, Andrew Malek, Natasha C. Brigham, Matthew L. Becker, Ken Gall, Benjamin J. Wiley. Advanced Functional Materials DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202205662 First published: 04 August 2022

This paper is behind a paywall.

You can find Sparta Biomedical here.