There are two news bits about game-changing electronics, one from the UK and the other from the US.

United Kingdom (UK)

An April 3, 2017 news item on Azonano announces the possibility of a future golden age of electronics courtesy of the University of Exeter,

Engineering experts from the University of Exeter have come up with a breakthrough way to create the smallest, quickest, highest-capacity memories for transparent and flexible applications that could lead to a future golden age of electronics.

A March 31, 2017 University of Exeter press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on the theme (Note: Links have been removed),

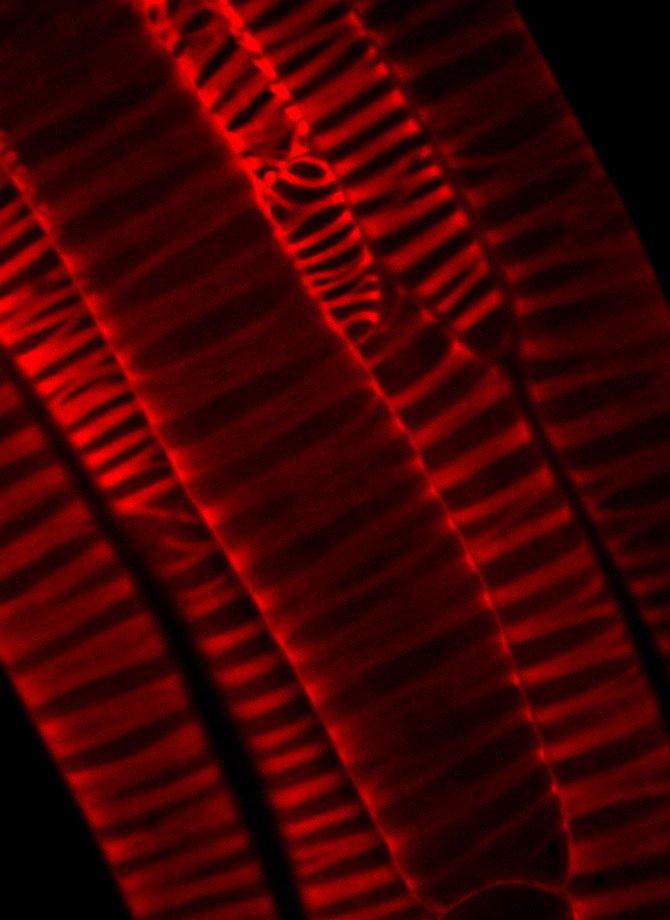

Engineering experts from the University of Exeter have developed innovative new memory using a hybrid of graphene oxide and titanium oxide. Their devices are low cost and eco-friendly to produce, are also perfectly suited for use in flexible electronic devices such as ‘bendable’ mobile phone, computer and television screens, and even ‘intelligent’ clothing.

Crucially, these devices may also have the potential to offer a cheaper and more adaptable alternative to ‘flash memory’, which is currently used in many common devices such as memory cards, graphics cards and USB computer drives.

The research team insist that these innovative new devices have the potential to revolutionise not only how data is stored, but also take flexible electronics to a new age in terms of speed, efficiency and power.

…

Professor David Wright, an Electronic Engineering expert from the University of Exeter and lead author of the paper said: “Using graphene oxide to produce memory devices has been reported before, but they were typically very large, slow, and aimed at the ‘cheap and cheerful’ end of the electronics goods market.

“Our hybrid graphene oxide-titanium oxide memory is, in contrast, just 50 nanometres long and 8 nanometres thick and can be written to and read from in less than five nanoseconds – with one nanometre being one billionth of a metre and one nanosecond a billionth of a second.”

Professor Craciun, a co-author of the work, added: “Being able to improve data storage is the backbone of tomorrow’s knowledge economy, as well as industry on a global scale. Our work offers the opportunity to completely transform graphene-oxide memory technology, and the potential and possibilities it offers.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Multilevel Ultrafast Flexible Nanoscale Nonvolatile Hybrid Graphene Oxide–Titanium Oxide Memories by V. Karthik Nagareddy, Matthew D. Barnes, Federico Zipoli, Khue T. Lai, Arseny M. Alexeev, Monica Felicia Craciun, and C. David Wright. ACS Nano, 2017, 11 (3), pp 3010–3021 DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.6b08668 Publication Date (Web): February 21, 2017

Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society

This paper appears to be open access.

United States (US)

Researchers from Stanford University have developed flexible, biodegradable electronics.

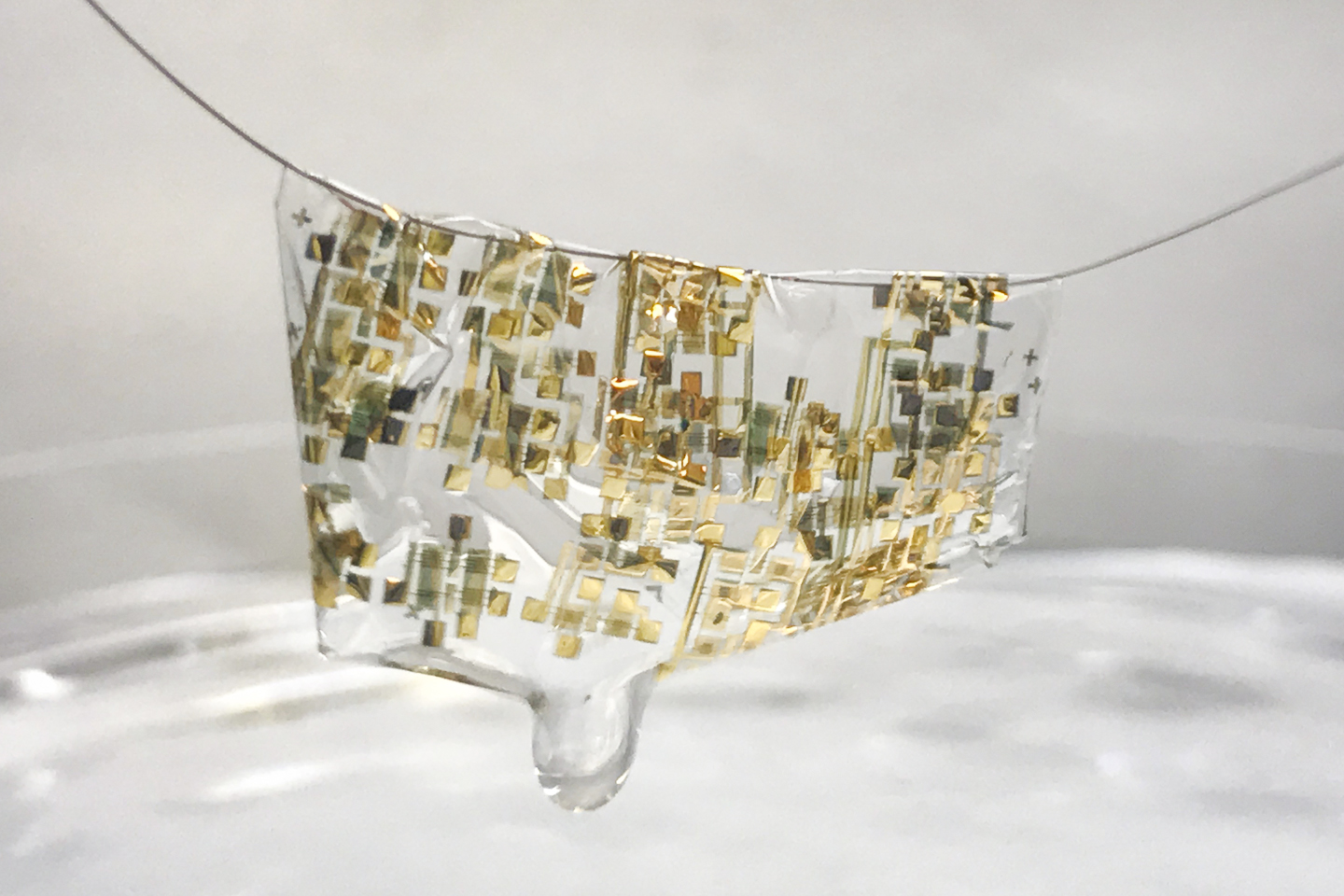

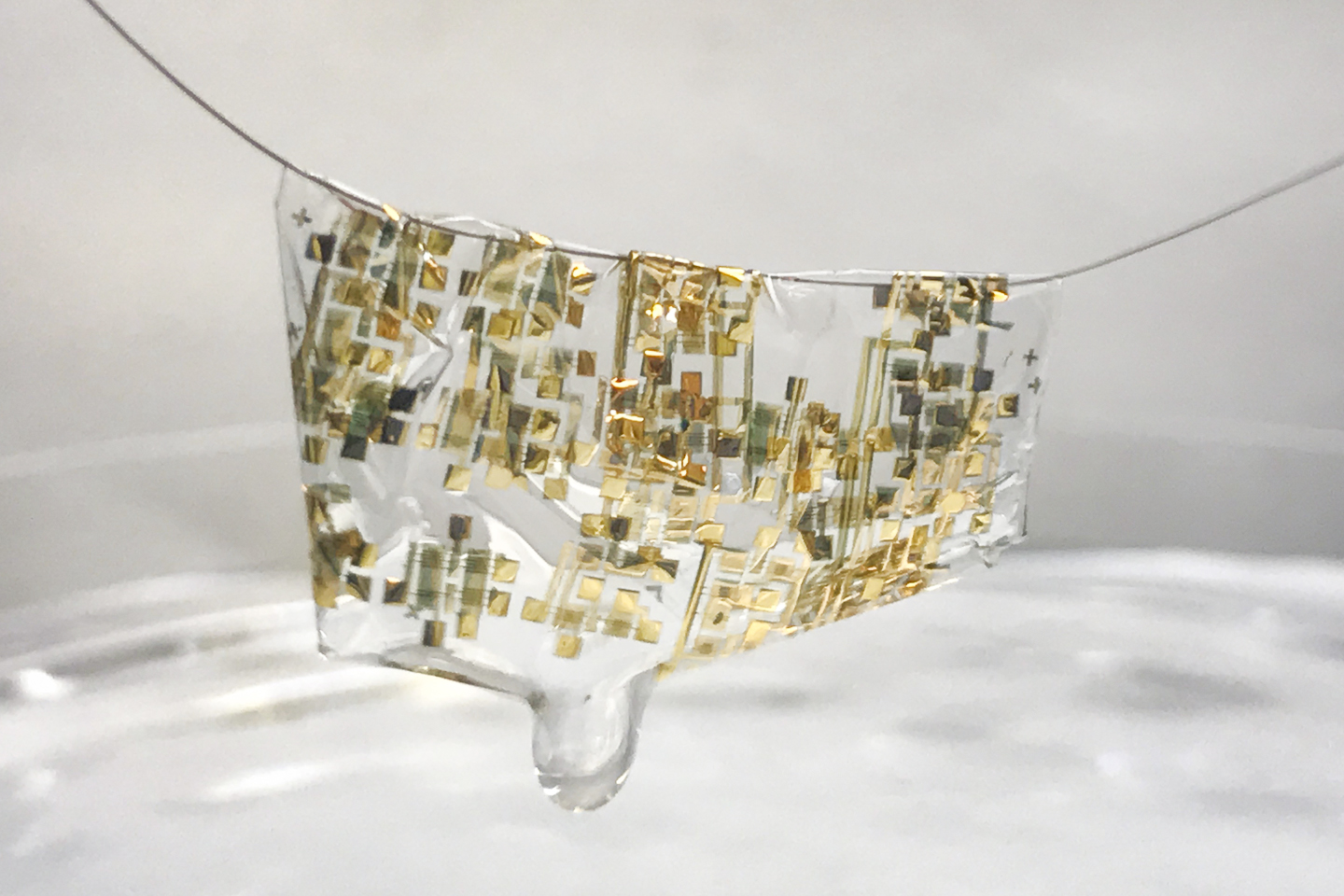

A newly developed flexible, biodegradable semiconductor developed by Stanford engineers shown on a human hair. (Image credit: Bao lab)

A human hair? That’s amazing and this May 3, 2017 news item on Nanowerk reveals more,

As electronics become increasingly pervasive in our lives – from smart phones to wearable sensors – so too does the ever rising amount of electronic waste they create. A United Nations Environment Program report found that almost 50 million tons of electronic waste were thrown out in 2017–more than 20 percent higher than waste in 2015.

Troubled by this mounting waste, Stanford engineer Zhenan Bao and her team are rethinking electronics. “In my group, we have been trying to mimic the function of human skin to think about how to develop future electronic devices,” Bao said. She described how skin is stretchable, self-healable and also biodegradable – an attractive list of characteristics for electronics. “We have achieved the first two [flexible and self-healing], so the biodegradability was something we wanted to tackle.”

The team created a flexible electronic device that can easily degrade just by adding a weak acid like vinegar. The results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (“Biocompatible and totally disintegrable semiconducting polymer for ultrathin and ultralightweight transient electronics”).

“This is the first example of a semiconductive polymer that can decompose,” said lead author Ting Lei, a postdoctoral fellow working with Bao.

A May 1, 2017 Stanford University news release by Sarah Derouin, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

In addition to the polymer – essentially a flexible, conductive plastic – the team developed a degradable electronic circuit and a new biodegradable substrate material for mounting the electrical components. This substrate supports the electrical components, flexing and molding to rough and smooth surfaces alike. When the electronic device is no longer needed, the whole thing can biodegrade into nontoxic components.

Biodegradable bits

Bao, a professor of chemical engineering and materials science and engineering, had previously created a stretchable electrode modeled on human skin. That material could bend and twist in a way that could allow it to interface with the skin or brain, but it couldn’t degrade. That limited its application for implantable devices and – important to Bao – contributed to waste.

The flexible semiconductor can adhere to smooth or rough surfaces and biodegrade to nontoxic products. (Image credit: Bao lab)

Bao said that creating a robust material that is both a good electrical conductor and biodegradable was a challenge, considering traditional polymer chemistry. “We have been trying to think how we can achieve both great electronic property but also have the biodegradability,” Bao said.

Eventually, the team found that by tweaking the chemical structure of the flexible material it would break apart under mild stressors. “We came up with an idea of making these molecules using a special type of chemical linkage that can retain the ability for the electron to smoothly transport along the molecule,” Bao said. “But also this chemical bond is sensitive to weak acid – even weaker than pure vinegar.” The result was a material that could carry an electronic signal but break down without requiring extreme measures.

In addition to the biodegradable polymer, the team developed a new type of electrical component and a substrate material that attaches to the entire electronic component. Electronic components are usually made of gold. But for this device, the researchers crafted components from iron. Bao noted that iron is a very environmentally friendly product and is nontoxic to humans.

The researchers created the substrate, which carries the electronic circuit and the polymer, from cellulose. Cellulose is the same substance that makes up paper. But unlike paper, the team altered cellulose fibers so the “paper” is transparent and flexible, while still breaking down easily. The thin film substrate allows the electronics to be worn on the skin or even implanted inside the body.

From implants to plants

The combination of a biodegradable conductive polymer and substrate makes the electronic device useful in a plethora of settings – from wearable electronics to large-scale environmental surveys with sensor dusts.

“We envision these soft patches that are very thin and conformable to the skin that can measure blood pressure, glucose value, sweat content,” Bao said. A person could wear a specifically designed patch for a day or week, then download the data. According to Bao, this short-term use of disposable electronics seems a perfect fit for a degradable, flexible design.

And it’s not just for skin surveys: the biodegradable substrate, polymers and iron electrodes make the entire component compatible with insertion into the human body. The polymer breaks down to product concentrations much lower than the published acceptable levels found in drinking water. Although the polymer was found to be biocompatible, Bao said that more studies would need to be done before implants are a regular occurrence.

Biodegradable electronics have the potential to go far beyond collecting heart disease and glucose data. These components could be used in places where surveys cover large areas in remote locations. Lei described a research scenario where biodegradable electronics are dropped by airplane over a forest to survey the landscape. “It’s a very large area and very hard for people to spread the sensors,” he said. “Also, if you spread the sensors, it’s very hard to gather them back. You don’t want to contaminate the environment so we need something that can be decomposed.” Instead of plastic littering the forest floor, the sensors would biodegrade away.

As the number of electronics increase, biodegradability will become more important. Lei is excited by their advancements and wants to keep improving performance of biodegradable electronics. “We currently have computers and cell phones and we generate millions and billions of cell phones, and it’s hard to decompose,” he said. “We hope we can develop some materials that can be decomposed so there is less waste.”

Other authors on the study include Ming Guan, Jia Liu, Hung-Cheng Lin, Raphael Pfattner, Leo Shaw, Allister McGuire, and Jeffrey Tok of Stanford University; Tsung-Ching Huang of Hewlett Packard Enterprise; and Lei-Lai Shao and Kwang-Ting Cheng of University of California, Santa Barbara.

The research was funded by the Air Force Office for Scientific Research; BASF; Marie Curie Cofund; Beatriu de Pinós fellowship; and the Kodak Graduate Fellowship.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the team’s latest paper,

Biocompatible and totally disintegrable semiconducting polymer for ultrathin and ultralightweight transient electronics by Ting Lei, Ming Guan, Jia Liu, Hung-Cheng Lin, Raphael Pfattner, Leo Shaw, Allister F. McGuire, Tsung-Ching Huang, Leilai Shao, Kwang-Ting Cheng, Jeffrey B.-H. Tok, and Zhenan Bao. PNAS 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701478114 published ahead of print May 1, 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.

The mention of cellulose in the second item piqued my interest so I checked to see if they’d used nanocellulose. No, they did not. Microcrystalline cellulose powder was used to constitute a cellulose film but they found a way to render this film at the nanoscale. From the Stanford paper (Note: Links have been removed),

… Moreover, cellulose films have been previously used as biodegradable substrates in electronics (28⇓–30). However, these cellulose films are typically made with thicknesses well over 10 μm and thus cannot be used to fabricate ultrathin electronics with substrate thicknesses below 1–2 μm (7, 18, 19). To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports on ultrathin (1–2 μm) biodegradable substrates for electronics. Thus, to realize them, we subsequently developed a method described herein to obtain ultrathin (800 nm) cellulose films (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). First, microcrystalline cellulose powders were dissolved in LiCl/N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) and reacted with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) (31, 32), providing trimethylsilyl-functionalized cellulose (TMSC) (Fig. 1B). To fabricate films or devices, TMSC in chlorobenzene (CB) (70 mg/mL) was spin-coated on a thin dextran sacrificial layer. The TMSC film was measured to be 1.2 μm. After hydrolyzing the film in 95% acetic acid vapor for 2 h, the trimethylsilyl groups were removed, giving a 400-nm-thick cellulose film. The film thickness significantly decreased to one-third of the original film thickness, largely due to the removal of the bulky trimethylsilyl groups. The hydrolyzed cellulose film is insoluble in most organic solvents, for example, toluene, THF, chloroform, CB, and water. Thus, we can sequentially repeat the above steps to obtain an 800-nm-thick film, which is robust enough for further device fabrication and peel-off. By soaking the device in water, the dextran layer is dissolved, starting from the edges of the device to the center. This process ultimately releases the ultrathin substrate and leaves it floating on water surface (Fig. 3A, Inset).

Finally, I don’t have any grand thoughts; it’s just interesting to see different approaches to flexible electronics.