A December 31, 2022 news item on phys.org describes research into replacing silicon in the field of electronics, Note: Links have been removed,

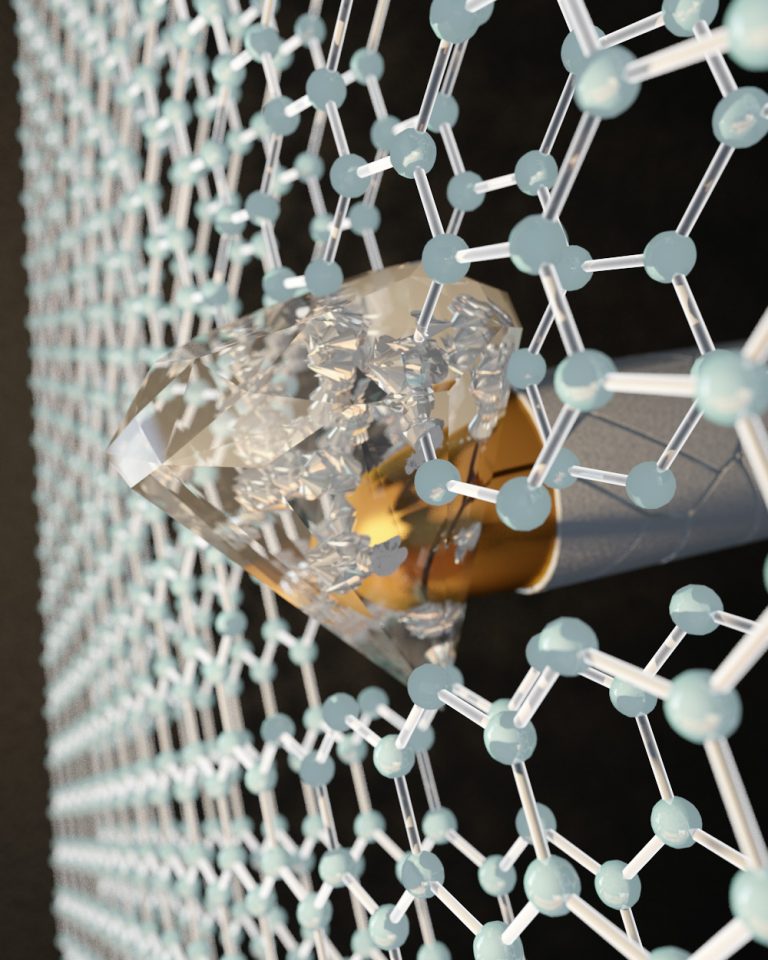

A pressing quest in the field of nanoelectronics is the search for a material that could replace silicon. Graphene has seemed promising for decades. But its potential has faltered along the way, due to damaging processing methods and the lack of a new electronics paradigm to embrace it. With silicon nearly maxed out in its ability to accommodate faster computing, the next big nanoelectronics platform is needed now more than ever.

Walter de Heer, Regents’ Professor in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology [Georgia Tech], has taken a critical step forward in making the case for a successor to silicon. De Heer and his collaborators have developed a new nanoelectronics platform based on graphene—a single sheet of carbon atoms. The technology is compatible with conventional microelectronics manufacturing, a necessity for any viable alternative to silicon.

In the course of their research, published in Nature Communications, the team may have also discovered a new quasiparticle. Their discovery could lead to manufacturing smaller, faster, more efficient and more sustainable computer chips, and has potential implications for quantum and high-performance computing.

…

A January 3, 2023 Georgia Institute of Technology news release (also on EurekAlert but published December 21, 2022] by Catherine Barzler, which originated the news item, delves further into the work

“Graphene’s power lies in its flat, two-dimensional structure that is held together by the strongest chemical bonds known,” de Heer said. “It was clear from the beginning that graphene can be miniaturized to a far greater extent than silicon — enabling much smaller devices, while operating at higher speeds and producing much less heat. This means that, in principle, more devices can be packed on a single chip of graphene than with silicon.”

In 2001, de Heer proposed an alternative form of electronics based on epitaxial graphene, or epigraphene — a layer of graphene that was found to spontaneously form on top of silicon carbide crystal, a semiconductor used in high power electronics. At the time, researchers found that electric currents flow without resistance along epigraphene’s edges, and that graphene devices could be seamlessly interconnected without metal wires. This combination allows for a form of electronics that relies on the unique light-like properties of graphene electrons.

“Quantum interference has been observed in carbon nanotubes at low temperatures, and we expect to see similar effects in epigraphene ribbons and networks,” de Heer said. “This important feature of graphene is not possible with silicon.”

Building the Platform

To create the new nanoelectronics platform, the researchers created a modified form of epigraphene on a silicon carbide crystal substrate. In collaboration with researchers at the Tianjin International Center for Nanoparticles and Nanosystems at the University of Tianjin, China, they produced unique silicon carbide chips from electronics-grade silicon carbide crystals. The graphene itself was grown at de Heer’s laboratory at Georgia Tech using patented furnaces.

The researchers used electron beam lithography, a method commonly used in microelectronics, to carve the graphene nanostructures and weld their edges to the silicon carbide chips. This process mechanically stabilizes and seals the graphene’s edges, which would otherwise react with oxygen and other gases that might interfere with the motion of the charges along the edge.

Finally, to measure the electronic properties of their graphene platform, the team used a cryogenic apparatus that allows them to record its properties from a near-zero temperature to room temperature.

Observing the Edge State

The electric charges the team observed in the graphene edge state were similar to photons in an optical fiber that can travel over large distances without scattering. They found that the charges traveled for tens of thousands of nanometers along the edge before scattering. Graphene electrons in previous technologies could only travel about 10 nanometers before bumping into small imperfections and scattering in different directions.

“What’s special about the electric charges in the edges is that they stay on the edge and keep on going at the same speed, even if the edges are not perfectly straight,” said Claire Berger, physics professor at Georgia Tech and director of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Grenoble, France.

In metals, electric currents are carried by negatively charged electrons. But contrary to the researchers’ expectations, their measurements suggested that the edge currents were not carried by electrons or by holes (a term for positive quasiparticles indicating the absence of an electron). Rather, the currents were carried by a highly unusual quasiparticle that has no charge and no energy, and yet moves without resistance. The components of the hybrid quasiparticle were observed to travel on opposite sides of the graphene’s edges, despite being a single object.

The unique properties indicate that the quasiparticle might be one that physicists have been hoping to exploit for decades — the elusive Majorana fermion predicted by Italian theoretical physicist Ettore Majorana in 1937.

“Developing electronics using this new quasiparticle in seamlessly interconnected graphene networks is game changing,” de Heer said.

It will likely be another five to 10 years before we have the first graphene-based electronics, according to de Heer. But thanks to the team’s new epitaxial graphene platform, technology is closer than ever to crowning graphene as a successor to silicon.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

An epitaxial graphene platform for zero-energy edge state nanoelectronics by Vladimir S. Prudkovskiy, Yiran Hu, Kaimin Zhang, Yue Hu, Peixuan Ji, Grant Nunn, Jian Zhao, Chenqian Shi, Antonio Tejeda, David Wander, Alessandro De Cecco, Clemens B. Winkelmann, Yuxuan Jiang, Tianhao Zhao, Katsunori Wakabayashi, Zhigang Jiang, Lei Ma, Claire Berger & Walt A. de Heer. Nature Communications volume 13, Article number: 7814 (2022) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34369-4 Published 19 December 2022

This paper is open access.