Somewhere in my travels, I saw ‘like watching paint dry’ as a description for the experience of watching researchers examining Rembrandt’s Night Watch. Granted it’s probably not that exciting but there has to be something to be said for being present while experts undertake an extraordinary art restoration effort. The Night Watch is not only a masterpiece—it’s huge.

This posting was written closer to the time the ‘live’ restoration first began. I have an update at the end of this posting.

A July 8, 2019 news item on the British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) news online sketches in some details,

The masterpiece, created in 1642, has been placed inside a specially designed glass chamber so that it can still be viewed while being restored.

Enthusiasts can follow the latest on the restoration work online.

The celebrated painting was last restored more than 40 years ago after it was slashed with a knife.

The Night Watch is considered Rembrandt’s most ambitious work. It was commissioned by the mayor and leader of the civic guard of Amsterdam, Frans Banninck Cocq, who wanted a group portrait of his militia company.

…

The painting is nearly 4m tall and 4.5m wide (12.5 x 15 ft) and weighs 337kg (743lb) [emphasis mine]. As well as being famous for its size, the painting is acclaimed for its use of dramatic lighting and movement.

But experts at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum are concerned that aspects of the masterpiece are changing, pointing as an example to the blanching of the figure of a small dog. The museum said the multi-million euro research and restoration project under way would help staff gain a better understanding of the painting’s condition.

…

An October 16, 2018 Rijksmuseum press release announced the restoration work months prior to the start (Note: Some of the information is repetitive;),

Before the restoration begins, The Night Watch will be the centrepiece of the Rijksmuseum’s display of their entire collection of more than 400 works by Rembrandt in an exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the artist’s death opening on 15 February 2019.

…

Commissioned in 1642 by the mayor and leader of the civic guard of Amsterdam, Frans Banninck Cocq, to create a group portrait of his shooting company, The Night Watch is recognised as one of the most important works of art in the world today and hangs in the specially designed “Gallery of Honour” at the Rijksmuseum. It is more than 40 years since The Night Watch underwent its last major restoration, following an attack on the painting in 1975.

The Night Watch will be encased in a state-of-the-art clear glass chamber designed by the French architect Jean Michel Wilmotte. This will ensure that the painting can remain on display for museum visitors. A digital platform will allow viewers from all over the world to follow the entire process online [emphasis mine] continuing the Rijksmuseum innovation in the digital field.

Taco Dibbits, General Director Rijksmuseum: The Night Watch is one of the most famous paintings in the world. It belongs to us all, and that is why we have decided to conduct the restoration within the museum itself – and everyone, wherever they are, will be able to follow the process online.

The Rijksmuseum continually monitors the condition of The Night Watch, and it has been discovered that changes are occurring, such as the blanching [emphasis mine] on the dog figure at the lower right of the painting. To gain a better understanding of its condition as a whole, the decision has been taken to conduct a thorough examination. This detailed study is necessary to determine the best treatment plan, and will involve imaging techniques, high-resolution photography and highly advanced computer analysis. Using these and other methods, we will be able to form a very detailed picture of the painting – not only of the painted surface, but of each and every layer, from varnish to canvas.

A great deal of experience has been gained in the Rijksmuseum relating to the restoration of Rembrandt’s paintings. Last year saw the completion of the restoration of Rembrandt’s spectacular portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit. The research team working on The Night Watch is made up of researchers, conservators and restorers from the Rijksmuseum, which will conduct this research in close collaboration with museums and universities in the Netherlands and abroad.

…

The Night Watch

The group portrait of the officers and other members of the militia company of District II, under the command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch, now known as The Night Watch, is Rembrandt’s most ambitious painting. This 1642 commission by members of Amsterdam’s civic guard is Rembrandt’s first and only painting of a militia group. It is celebrated particularly for its bold and energetic composition, with the musketeers being depicted ‘in motion’, rather than in static portrait poses. The Night Watch belongs to the city of Amsterdam, and it been the highlight of the Rijksmuseum collection since 1808. The architect of the Rijksmuseum building Pierre Cuypers (1827-1921) even created a dedicated gallery of honour for The Night Watch, and it is now admired there by more than 2.2 million people annually.

2019, The Year of Rembrandt

The Year of Rembrandt, 2019, marks the 350th anniversary of the artist’s death with two major exhibitions honouring the great master painter. All the Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum (15 February to 10 June 2019) will bring together the Rijksmuseum’s entire collection of Rembrandt’s paintings, drawings and prints, for the first time in history. The second exhibition, Rembrandt-Velázquez (11 October 2019 to 19 January 2020), will put the master in international context by placing 17th-century Spanish and Dutch masterpieces in dialogue with each another.

…

First, the restoration work is not being livestreamed; the digital platform Operation Night Watch is a collection of resources, which are being updated constantly, For example, the first scan was placed online in Operation Night Watch on July 16, 2019.

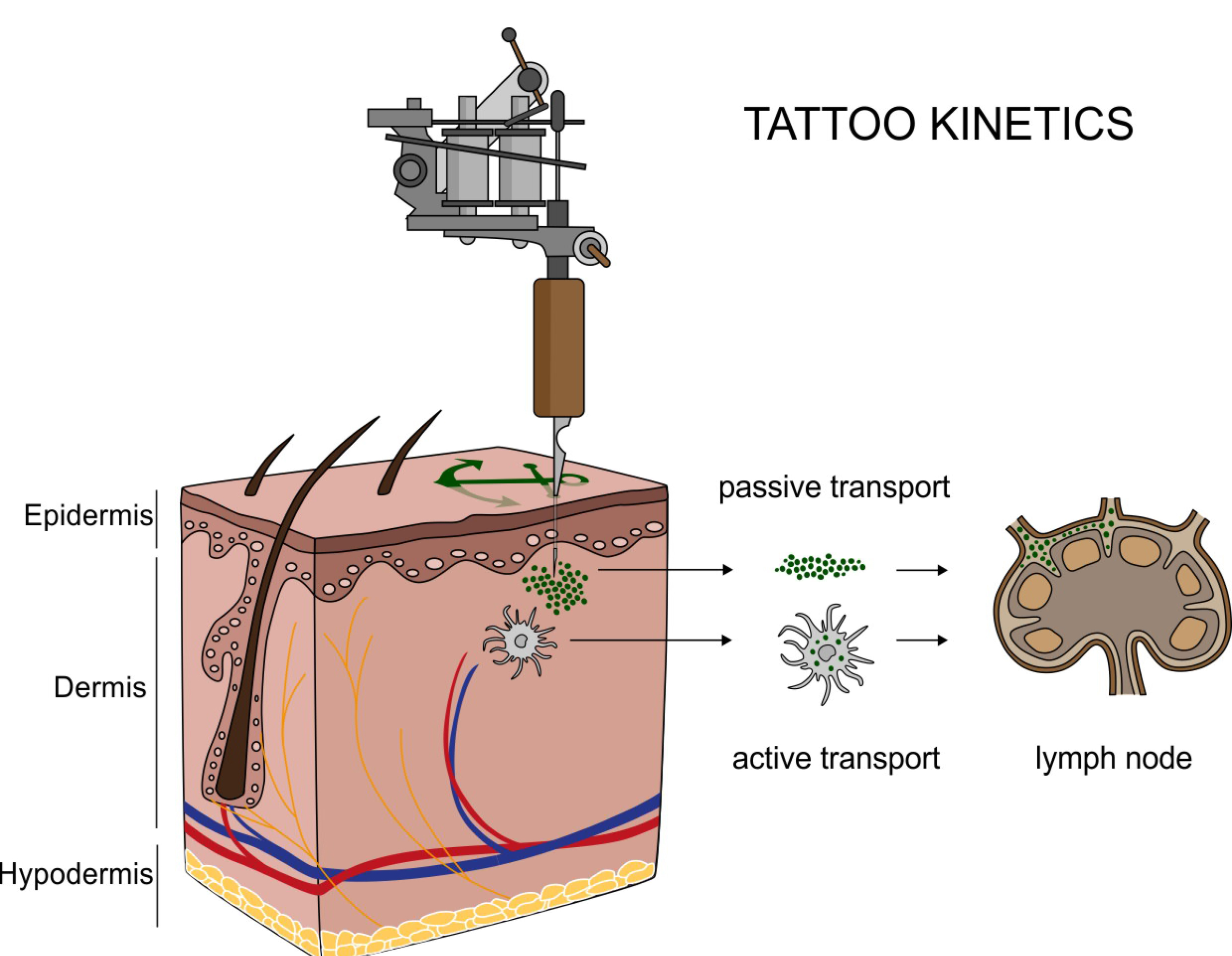

Second, ‘blanching’ reminded me of a June 22, 2017 posting where I featured research into why masterpieces were turning into soap, (Note: The second paragraph should be indented to indicated that it’s an excerpt fro the news release. Unfortunately, the folks at WordPress appear to have removed the tools that would allow me to do that and more),

This piece of research has made a winding trek through the online science world. First it was featured in an April 20, 2017 American Chemical Society news release on EurekAlert

A good art dealer can really clean up in today’s market, but not when some weird chemistry wreaks havoc on masterpieces. Art conservators started to notice microscopic pockmarks forming on the surfaces of treasured oil paintings that cause the images to look hazy. It turns out the marks are eruptions of paint caused, weirdly, by soap that forms via chemical reactions. Since you have no time to watch paint dry, we explain how paintings from Rembrandts to O’Keefes are threatened by their own compositions — and we don’t mean the imagery.

….

Getting back to the Night Watch, there’s a July 8, 2019 Rijksmuseum press release which provides some technical details,

On 8 July 2019 the Rijksmuseum starts Operation Night Watch. It will be the biggest and most wide-ranging research and conservation project in the history of Rembrandt’s masterpiece. The goal of Operation Night Watch is the long-term preservation of the painting. The entire operation will take place in a specially designed glass chamber so the visiting public can watch.

Never before has such a wide-ranging and thorough investigation been made of the condition of The Night Watch. The latest and most advanced research techniques will be used, ranging from digital imaging and scientific and technical research, to computer science and artificial intelligence. The research will lead to a better understanding of the painting’s original appearance and current state, and provide insight into the many changes that The Night Watch has undergone over the course of the last four centuries. The outcome of the research will be a treatment plan that will form the basis for the restoration of the painting.

Operation Night Watch can also be followed online from 8 July 2019 at rijksmuseum.nl/nightwatch

From art historical research to artificial intelligence

Operation Night Watch will look at questions regarding the original commission, Rembrandt’s materials and painting technique, the impact of previous treatments and later interventions, as well as the ageing, degradation and future of the painting. This will involve the newest and most advanced research methods and technologies, including art historical and archival research, scientific and technical research, computer science and artificial intelligence.

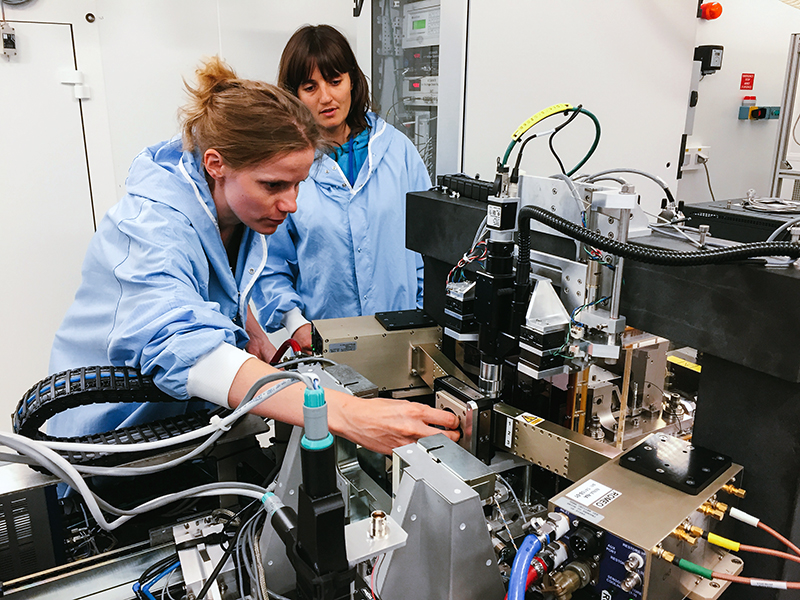

During the research phase The Night Watch will be unframed and placed on a specially designed easel. Two platform lifts will make it possible to study the entire canvas, which measures 379.5 cm in height and 454.5 cm in width.

Advanced imaging techniques

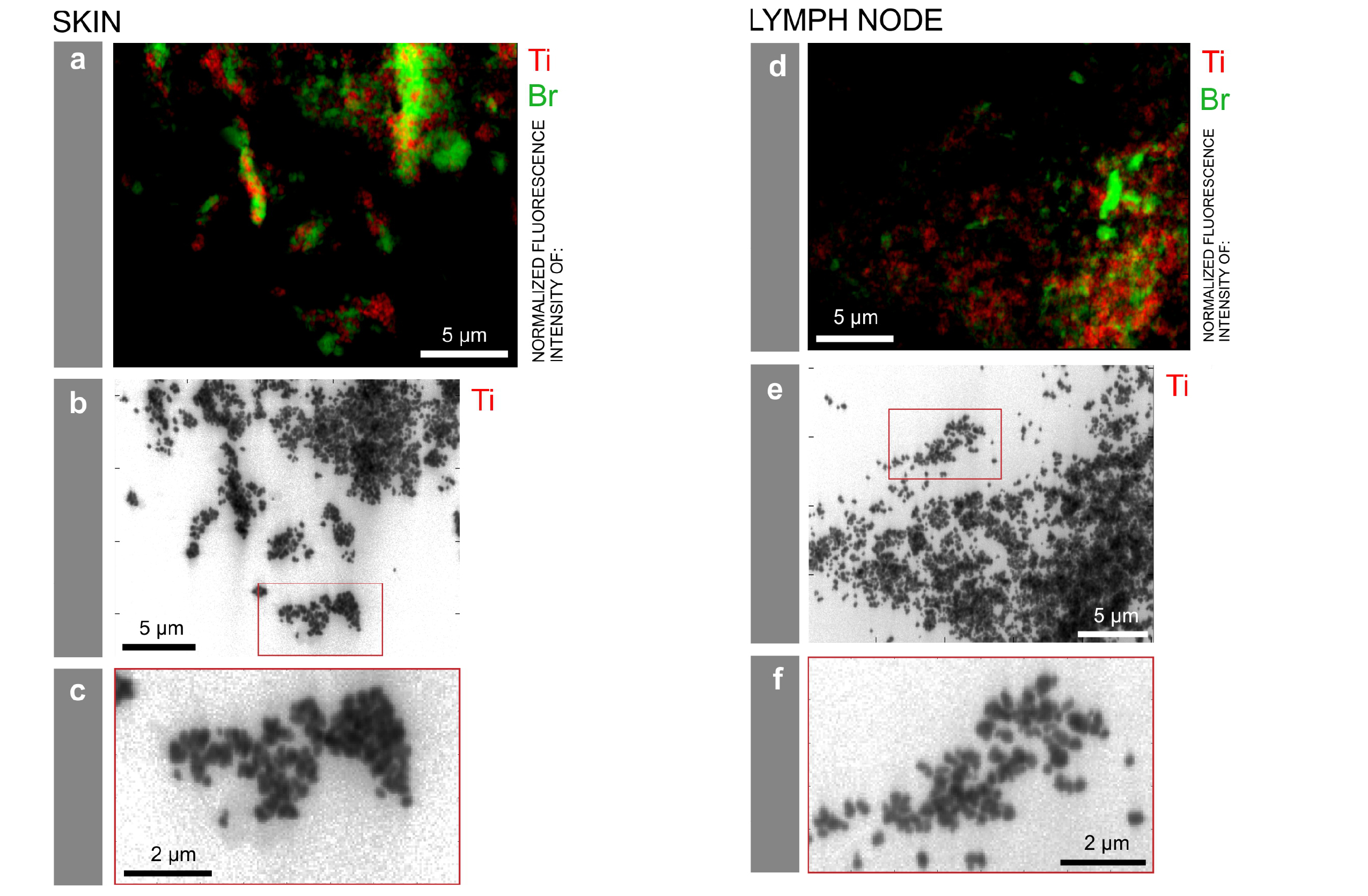

Researchers will make use of high resolution photography, as well as a variety of advanced imaging techniques, such as macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (macro-XRF) and hyperspectral imaging, also called infrared reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS), to accurately determine the condition of the painting.

56 macro-XRF scans

The Night Watch will be scanned millimetre by millimetre using a macro X-ray fluorescence scanner (macro-XRF scanner). This instrument uses X-rays to analyse the different chemical elements in the paint, such as calcium, iron, potassium and cobalt. From the resulting distribution maps of the various chemical elements in the paint it is possible to determine which pigments were used. The macro-XRF scans can also reveal underlying changes in the composition, offering insights into Rembrandt’s painting process. To scan the entire surface of the The Night Watch it will be necesary to make 56 scans, each one of which will take 24 hours.

12,500 high-resolution photographs

A total of some 12,500 photographs will be taken at extremely high resolution, from 180 to 5 micrometres, or a thousandth of a millimetre. Never before has such a large painting been photographed at such high resolution. In this way it will be possible to see details such as pigment particles that normally would be invisible to the naked eye. The cameras and lamps will be attached to a dynamic imaging frame designed specifically for this purpose.

Glass chamber

Operation Night Watch is for everyone to follow and will take place in full view of the visiting public in an ultra-transparent glass chamber designed by the French architect Jean Michel Wilmotte.

Research team

The Rijksmuseum has extensive experience and expertise in the investigation and treatment of paintings by Rembrandt. The conservation treatment of Rembrandt’s portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit was completed in 2018. The research team working on The Night Watch is made up of more than 20 Rijksmuseum scientists, conservators, curators and photographers. For this research, the Rijksmuseum is also collaborating with museums and universities in the Netherlands and abroad, including the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency (RCE), Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), the University of Amsterdam (UvA), Amsterdam University Medical Centre (AUMC), University of Antwerp (UA) and National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

The Night Watch

Rembrandt’s Night Watch is one of the world’s most famous works of art. The painting is the property of the City of Amsterdam, and it is the heart of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, where it is admired by more than two million visitors each year. The Night Watch is the Netherland’s foremost national artistic showpiece, and a must-see for tourists.

Rembrandt’s group portrait of officers and other civic guardsmen of District 2 in Amsterdam under the command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch has been known since the 18th century as simply The Night Watch. It is the artist’s most ambitious painting. One of Amsterdam’s 20 civic guard companies commissioned the painting for its headquarters, the Kloveniersdoelen, and Rembrandt completed it in 1642. It is Rembrandt’s only civic guard piece, and it is famed for the lively and daring composition that portrays the troop in active poses rather than the traditional static ones.

Donors and partners

AkzoNobel is main partner of Operation Night Watch.

Operation Night Watch is made possible by The Bennink Foundation, PACCAR Foundation, Piet van der Slikke & Sandra Swelheim, American Express Foundation, Familie De Rooij, Het AutoBinck Fonds, Segula Technologies, Dina & Kjell Johnsen, Familie D. Ermia, Familie M. van Poecke, Henry M. Holterman Fonds, Irma Theodora Fonds, Luca Fonds, Piek-den Hartog Fonds, Stichting Zabawas, Cevat Fonds, Johanna Kast-Michel Fonds, Marjorie & Jeffrey A. Rosen, Stichting Thurkowfonds and the Night Watch Fund.

With the support of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the City of Amsterdam, Founder Philips and main sponsors ING, BankGiro Loterij and KPN every year more than 2 million people visit the Rijksmuseum and The Night Watch.

Details:

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

The Night Watch, 1642

oil on canvas

Rijksmuseum, on loan from the Municipality of Amsterdam

Update as of November 22, 2019

I just clicked on the Operation Night Watch link and found a collection of resources including videos of live updates from October 2019. As noted earlier, they’re not livestreaming the restoration. The October 29, 2019 ‘live update’ features a host speaking in Dutch (with English subtitles in the version I was viewing) and interviews with the scientists conducting the research necessary before they start actually restoring the painting.