I have two items about concrete buildings, one concerns the June 24, 2021 collapse of a 12-storey condominium building in Surfside, close to Miami Beach in Florida. There are at least 20 people dead and, I believe, over 120 are still unaccounted for (July 2, 2021 Associated Press news item on Canadian Broadcasting Corporation news online website).

Miami collapse

Nate Berg’s June 25, 2021 article for Fast Company provides an instructive overview of the building collapse (Note: A link has been removed),

…

Why the building collapsed is not yet known [emphasis mine]. David Darwin is a professor of civil engineering at the University of Kansas and an expert in reinforced concrete structures, and he says the eventual investigation of the Surfside collapse will explore all the potential causes, ranging from movement in the foundation before the collapse, corrosion in the debris, and excessive cracking in the part of the building that remains standing. “There are all sorts of potential causes of failure,” Darwin says. “At this point, speculation is not helpful for anybody.”

…

Sometimes I can access the entire article, and at other times, only a few paragraphs; I hope you get access to all of it as it provides a lot of information.

The Surfside news puts this research from Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois) into much sharper relief than might otherwise be the case. (Further on I have some information about the difference between cement and concrete and how cement leads to concrete.)

Smart cement for more durable roads and cities

Coincidentally, just days before the Miami Beach building collapse, a June 21, 2021 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert), announced research into improving water and fracture resistance in cement,

Forces of nature have been outsmarting the materials we use to build our infrastructure since we started producing them. Ice and snow turn major roads into rubble every year; foundations of houses crack and crumble, in spite of sturdy construction. In addition to the tons of waste produced by broken bits of concrete, each lane-mile of road costs the U.S. approximately $24,000 per year to keep it in good repair.

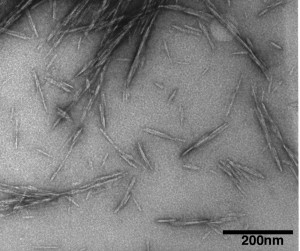

Engineers tackling this issue with smart materials typically enhance the function of materials by increasing the amount of carbon, but doing so makes materials lose some mechanical performance. By introducing nanoparticles into ordinary cement, Northwestern University researchers have formed a smarter, more durable and highly functional cement.

The research was published today (June 21 [2021]) in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

With cement being the most widely consumed material globally and the cement industry accounting for 8% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, civil and environmental engineering professor Ange-Therese Akono turned to nanoreinforced cement to look for a solution. Akono, the lead author on the study and an assistant professor in the McCormick School of Engineering, said nanomaterials reduce the carbon footprint of cement composites, but until now, little was known about its impact on fracture behavior.

“The role of nanoparticles in this application has not been understood before now, so this is a major breakthrough,” Akono said. “As a fracture mechanics expert by training, I wanted to understand how to change cement production to enhance the fracture response.”

Traditional fracture testing, in which a series of light beams is cast onto a large block of material, involves lots of time and materials and seldom leads to the discovery of new materials.

By using an innovative method called scratch testing, Akono’s lab efficiently formed predictions on the material’s properties in a fraction of the time. The method tests fracture response by applying a conical probe with increasing vertical force against the surface of microscopic bits of cement. Akono, who developed the novel method during her Ph.D. work, said it requires less material and accelerates the discovery of new ones.

“I was able to look at many different materials at the same time,” Akono said. “My method is applied directly at the micrometer and nanometer scales, which saves a considerable amount of time. And then based on this, we can understand how materials behave, how they crack and ultimately predict their resistance to fracture.”

Predictions formed through scratch tests also allow engineers to make changes to materials that enhance their performance at the larger scale. In the paper, graphene nanoplatelets, a material rapidly gaining popularity in forming smart materials, were used to improve the resistance to fracture of ordinary cement. Incorporating a small amount of the nanomaterial also was shown to improve water transport properties including pore structure and water penetration resistance, with reported relative decreases of 76% and 78%, respectively.

Implications of the study span many fields, including building construction, road maintenance, sensor and generator optimization and structural health monitoring.

By 2050, the United Nations predicts two-thirds of the world population will be concentrated in cities. Given the trend toward urbanization, cement production is expected to skyrocket.

Introducing green concrete that employs lighter, higher-performing cement will reduce its overall carbon footprint by extending maintenance schedules and reducing waste.

Alternately, smart materials allow cities to meet the needs of growing populations in terms of connectivity, energy and multifunctionality. Carbon-based nanomaterials including graphene nanoplatelets are already being considered in the design of smart cement-based sensors for structural health monitoring.

Akono said she’s excited for both follow-ups to the paper in her own lab and the ways her research will influence others. She’s already working on proposals that look into using construction waste to form new concrete and is considering “taking the paper further” by increasing the fraction of nanomaterial that cement contains.

“I want to look at other properties like understanding the long-term performance,” Akono said. “For instance, if you have a building made of carbon-based nanomaterials, how can you predict the resistance in 10, 20 even 40 years?”

The study, “Fracture toughness of one- and two-dimensional nanoreinforced cement via scratch testing,” was supported by the National Science Foundation Division of Civil, Mechanical and Manufacturing Innovation (award number 18929101).

Akono will give a talk on the paper at The Royal Society’s October [2021] meeting, “A Cracking Approach to Inventing Tough New Materials: Fracture Stranger Than Friction,” which will highlight major advances in fracture mechanics from the past century.

I don’t often include these kinds of photos (one or more of the researchers posing (sometimes holding something) for the camera but I love the professor’s first name, Ange-Therese (which means angel in French, I don’t know if she ever uses the French spelling for Thérèse),

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Fracture toughness of one- and two-dimensional nanoreinforced cement via scratch testing by Ange-Therese Akono. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical & Engineering Sciences 2021 379 (2203): 20200288 DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2020.0288 Published June 21, 2021

This paper appears to be open access.

Cement vs. concrete

Andrew Logan’s April 3, 2020 article for MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) News is a very readable explanation of how cement and concrete differ and how they are related,

There’s a lot the average person doesn’t know about concrete. For example, it’s porous; it’s the world’s most-used material after water; and, perhaps most fundamentally, it’s not cement.

Though many use “cement” and “concrete” interchangeably, they actually refer to two different — but related — materials: Concrete is a composite made from several materials, one of which is cement. [emphasis mine]

Cement production begins with limestone, a sedimentary rock. Once quarried, it is mixed with a silica source, such as industrial byproducts slag or fly ash, and gets fired in a kiln at 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. What comes out of the kiln is called clinker. Cement plants grind clinker down to an extremely fine powder and mix in a few additives. The final result is cement.

“Cement is then brought to sites where it is mixed with water, where it becomes cement paste,” explains Professor Franz-Josef Ulm, faculty director of the MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub (CSHub). “If you add sand to that paste it becomes mortar. And if you add to the mortar large aggregates — stones of a diameter of up to an inch — it becomes concrete.”

…

Final thoughts

I offer my sympathies to the folks affected by the building collapse and my hopes that research will lead the way to more durable cement and, ultimately, concrete buildings.