In the past I’ve covered work on the Namib beetle and its bumps which allow it to access condensation from the air in one of the hottest places on earth and work on jewel beetles and how their structural colo(u)r is derived. Now, there’s research into a beetle’s body armor from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln according to a Feb. 22, 2017 news item on ScienceDaily,

Beetles wear a body armor that should weigh them down — think medieval knights and turtles. In fact, those hard shells protecting delicate wings are surprisingly light, allowing even flight.

Better understanding the structure and properties of beetle exoskeletons could help scientists engineer lighter, stronger materials. Such materials could, for example, reduce gas-guzzling drag in vehicles and airplanes and reduce the weight of armor, lightening the load for the 21st-century knight.

But revealing exoskeleton architecture at the nanoscale has proven difficult. Nebraska’s Ruiguo Yang, assistant professor of mechanical and materials engineering, and his colleagues found a way to analyze the fibrous nanostructure. …

A Feb. 22, 2017 University of Nebraska-Lincoln news release by Gillian Klucas (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes skeletons and the work in more detail,

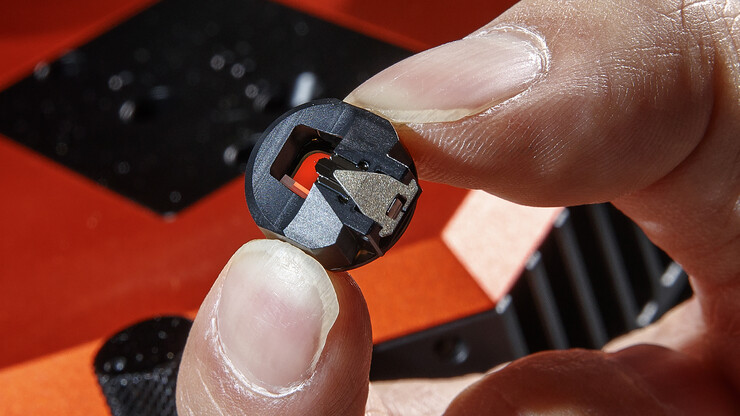

The lightweight exoskeleton is composed of chitin fibers just around 20 nanometers in diameter (a human hair measures approximately 75,000 nanometers in diameter) and packed and piled into layers that twist in a spiral, like a spiral staircase. The small diameter and helical twisting, known as Bouligand, make the structure difficult to analyze.

Yang and his team developed a method of slicing down the spiral to reveal a surface of cross-sections of fibers at different orientations. From that viewpoint, the researchers were able to analyze the fibers’ mechanical properties with the aid of an atomic force microscope. This type of microscope applies a tiny force to a test sample, deforms the sample and monitors the sample’s response. Combining the experimental procedure and theoretical analysis, the researchers were able to reveal the nanoscale architecture of the exoskeleton and the material properties of the nanofibers.

They made their discoveries in the common figeater beetle, Cotinis mutabilis, a metallic green native of the western United States. But the technique can be used on other beetles and hard-shelled creatures and might also extend to artificial materials with fibrous structures, Yang said.

Comparing beetles with differing demands on their exoskeletons, such as defending against predators or environmental damage, could lead to evolutionary insights as well as a better understanding of the relationship between structural features and their properties.

Yang’s co-authors are Alireza Zaheri and Horacio Espinosa of Northwestern University; Wei Gao of the University of Texas at San Antonio; and Cheryl Hayashi of the University of California, Riverside.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Exoskeletons: AFM Identification of Beetle Exocuticle: Bouligand Structure and Nanofiber Anisotropic Elastic Properties by Ruiguo Yang, Alireza Zaheri,Wei Gao, Charely Hayashi, Horacio D. Espinosa. Adv. Funct. Mater. vol. 27 (6) 2017 DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201770031 First published: 8 February 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.