I’ve never heard of a snout weevil before but it seems to be a marvelous creature,

From a Sept. 11, 2018 news item on Nanowerk,

Researchers from Yale [University]-NUS College and the University of Fribourg in Switzerland have discovered a novel colour-generation mechanism in nature, which if harnessed, has the potential to create cosmetics and paints with purer and more vivid hues, screen displays that project the same true image when viewed from any angle, and even reduce the signal loss in optical fibres.

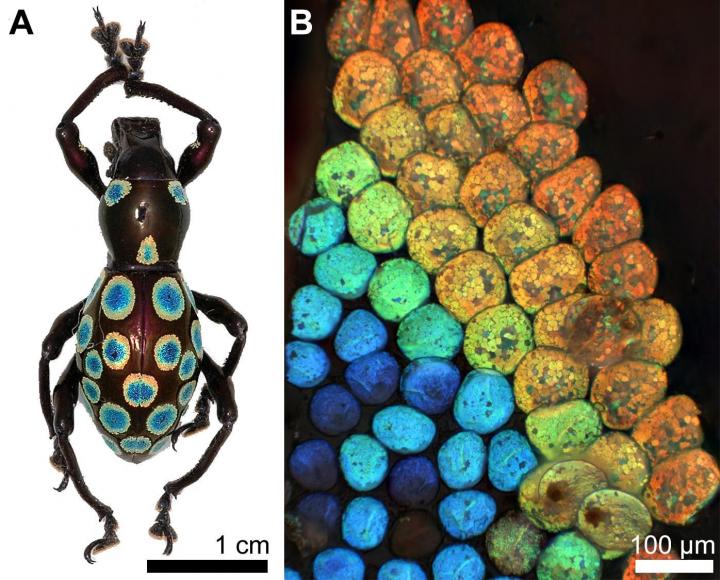

Yale-NUS College Assistant Professor of Science (Life Science) Vinodkumar Saranathan led the study with Dr Bodo D Wilts from the Adolphe Merkle Institute at the University of Fribourg. Dr Saranathan examined the rainbow-coloured patterns in the elytra (wing casings) of a snout weevil from the Philippines, Pachyrrhynchus congestus pavonius, using high-energy X-rays, while Dr Wilts performed detailed scanning electron microscopy and optical modelling.

They discovered that to produce the rainbow palette of colours, the weevil utilised a colour-generation mechanism that is so far found only in squid, cuttlefish, and octopuses, which are renowned for their colour-shifting camouflage.

A Sept. 11, 2018 Yale-NUS College news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, offers more on the weevil and on the research,

P. c. pavonius, or the “Rainbow” Weevil, is distinctive for its rainbow-coloured spots on its thorax and elytra (see attached image). These spots are made up of nearly-circular scales arranged in concentric rings of different hues, ranging from blue in the centre to red at the outside, just like a rainbow. While many insects have the ability to produce one or two colours, it is rare that a single insect can produce such a vast spectrum of colours. Researchers are interested to figure out the mechanism behind the natural formation of these colour-generating structures, as current technology is unable to synthesise structures of this size.

“The ultimate aim of research in this field is to figure out how the weevil self-assembles these structures, because with our current technology we are unable to do so,” Dr Saranathan said. “The ability to produce these structures, which are able to provide a high colour fidelity regardless of the angle you view it from, will have applications in any industry which deals with colour production. We can use these structures in cosmetics and other pigmentations to ensure high-fidelity hues, or in digital displays in your phone or tablet which will allow you to view it from any angle and see the same true image without any colour distortion. We can even use them to make reflective cladding for optical fibres to minimise signal loss during transmission.”

Dr Saranathan and Dr Wilts examined these scales to determine that the scales were composed of a three-dimensional crystalline structure made from chitin (the main ingredient in insect exoskeletons). They discovered that the vibrant rainbow colours on this weevil’s scales are determined by two factors: the size of the crystal structure which makes up each scale, as well as the volume of chitin used to make up the crystal structure. Larger scales have a larger crystalline structure and use a larger volume of chitin to reflect red light; smaller scales have a smaller crystalline structure and use a smaller volume of chitin to reflect blue light. According to Dr Saranathan, who previously examined over 100 species of insects and spiders and catalogued their colour-generation mechanisms, this ability to simultaneously control both size and volume factors to fine-tune the colour produced has never before been shown in insects, and given its complexity, is quite remarkable. “It is different from the usual strategy employed by nature to produce various different hues on the same animal, where the chitin structures are of fixed size and volume, and different colours are generated by orienting the structure at different angles, which reflects different wavelengths of light,” Dr Saranathan explained.

The research was partly supported though the National Centre of Competence in Research “Bio-Inspired Materials” and the Ambizione program of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) to Dr Wilts, and partly through a UK Royal Society Newton Fellowship, a Linacre College EPA Cephalosporin Junior Research Fellowship, and Yale-NUS College funds to Dr Saranathan. Dr Saranathan is currently part of a research team led by Yale-NUS College Associate Professor of Science Antonia Monteiro, which has recently been awarded a separate Competitive Research Programme (CRP) grant by Singapore’s National Research Foundation (NRF) to examine the genetic basis of the colour-generation mechanism in butterflies. Dr Saranathan and Dr Monteiro are both also from the Department of Biological Sciences at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Faculty of Science. In addition, Dr Saranathan is affiliated with the NUS Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Initiative.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Literal Elytral Rainbow: Tunable Structural Colors Using Single Diamond Biophotonic Crystals in Pachyrrhynchus congestus Weevils by Bodo D. Wilts, Vinodkumar Saranathan. Samll https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201802328 First published: 15 August 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.