I like the video animation that the scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have provided so much (particularly the raisins), I’m going to start with it,

The August 1, 2012 MIT news release on EurekAlert provides some additional detail,

This basic method, they say, could be harnessed for a wide variety of useful structures: microfluidic systems for biological research, sensing and diagnostics; new photonic devices that can control light waves; controllable adhesive surfaces; antireflective coatings; and antifouling surfaces that prevent microbial buildup.

A paper describing this new process, co-authored by MIT postdocs Jie Yin and Jose Luis Yagüe, former student Damien Eggenspieler SM ’10, and professors Mary Boyce and Karen Gleason, is being published in the journal Advanced Materials.

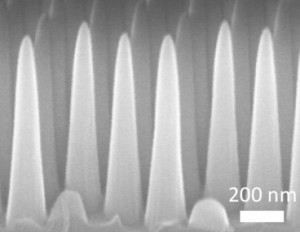

The process uses two layers of material. The bottom layer, or substrate, is a silicon-based polymer that can be stretched, like canvas mounted on a stretcher frame. Then, a second layer of polymeric material is deposited through an initiated chemical vapor deposition (iCVD) process in which the material is heated in a vacuum so that it vaporizes, and then lands on the stretched surface and bonds tightly to it. Then — and this is the key to the new process — the stretching is released first in one direction, and then in the other, rather than all at once.

When the tension is released all at once, the result is a jumbled, chaotic pattern of wrinkles, like the surface of a raisin. But the controlled, stepwise release system developed by the MIT team creates a perfectly orderly herringbone pattern.

The David Chandler Aug. 1, 2012 article (written for MIT) which originated the news release notes,

Many techniques have been used to create surfaces with such tiny patterns, whose dimensions can range from nanometers (billionths of a meter) to tens of micrometers (millionths of a meter). But most such methods require complex fabrication processes, or can only be used for very tiny areas.

The new method is both very simple (consisting of just two or three steps) and can be used to make patterned surfaces of larger sizes, the team says. “You don’t need an external template” to create the pattern, says Yin, the paper’s lead author.

…

John Hutchinson, a professor of engineering and of applied mechanics at Harvard University who was not involved in this research, says, “Wrinkling phenomena are highly nonlinear and answers to questions concerning pattern formation have been slow to emerge.” He says the MIT team’s work “is an important step forward in this active area of research that bridges the chemical and mechanical engineering communities. The advance rests on theoretical insights combined with experimental demonstration and numerical simulation — it covers all the bases.”The work was funded by the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals in Saudi Arabia.

It’s nice to see wrinkles being appreciated.