It’s fascinating to read about a technique for applying ‘tattoos’ to living cells and I have two news items and news releases with different perspectives about this same research.

First out the door was the August 7, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily,

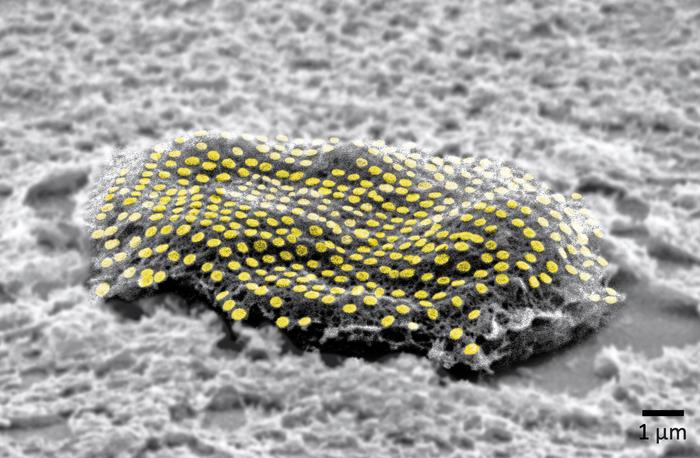

Engineers have developed nanoscale tattoos — dots and wires that adhere to live cells — in a breakthrough that puts researchers one step closer to tracking the health of individual cells.

The new technology allows for the first time the placement of optical elements or electronics on live cells with tattoo-like arrays that stick on cells while flexing and conforming to the cells’ wet and fluid outer structure.

“If you imagine where this is all going in the future, we would like to have sensors to remotely monitor and control the state of individual cells and the environment surrounding those cells in real time,” said David Gracias, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Johns Hopkins University who led the development of the technology. “If we had technologies to track the health of isolated cells, we could maybe diagnose and treat diseases much earlier and not wait until the entire organ is damaged.”

…

An August 7, 2023 Johns Hopkins University news release by (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the research in an accessible fashion before delving into technical details,

Gracias, who works on developing biosensor technologies that are nontoxic and noninvasive for the body, said the tattoos bridge the gap between living cells or tissue and conventional sensors and electronic materials. They’re essentially like barcodes or QR codes, he said.

“We’re talking about putting something like an electronic tattoo on a living object tens of times smaller than the head of a pin,” Gracias said. “It’s the first step towards attaching sensors and electronics on live cells.”

The structures were able to stick to soft cells for 16 hours even as the cells moved.

The researchers built the tattoos in the form of arrays with gold, a material known for its ability to prevent signal loss or distortion in electronic wiring. They attached the arrays to cells that make and sustain tissue in the human body, called fibroblasts. The arrays were then treated with molecular glues and transferred onto the cells using an alginate hydrogel film, a gel-like laminate that can be dissolved after the gold adheres to the cell. The molecular glue on the array bonds to a film secreted by the cells called the extracellular matrix.

Previous research has demonstrated how to use hydrogels to stick nanotechnology onto human skin and internal animal organs. By showing how to adhere nanowires and nanodots onto single cells, Gracias’ team is addressing the long-standing challenge of making optical sensors and electronics compatible with biological matter at the single cell level.

“We’ve shown we can attach complex nanopatterns to living cells, while ensuring that the cell doesn’t die,” Gracias said. “It’s a very important result that the cells can live and move with the tattoos because there’s often a significant incompatibility between living cells and the methods engineers use to fabricate electronics.”

The team’s ability to attach the dots and wires in an array form is also crucial. To use this technology to track bioinformation, researchers must be able to arrange sensors and wiring into specific patterns not unlike how they are arranged in electronic chips.

“This is an array with specific spacing,” Gracias explained, “not a haphazard bunch of dots.”

The team plans to try to attach more complex nanocircuits that can stay in place for longer periods. They also want to experiment with different types of cells.

Other Johns Hopkins authors are Kam Sang Kwok, Yi Zuo, Soo Jin Choi, Gayatri J. Pahapale, and Luo Gu.

This looks more like a sea creature to me but it’s not,

An August 10, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily offers a different perspective from the American Chemical Society (ACS) on this research,

For now, cyborgs exist only in fiction, but the concept is becoming more plausible as science progresses. And now, researchers are reporting in ACS’ Nano Letters that they have developed a proof-of-concept technique to “tattoo” living cells and tissues with flexible arrays of gold nanodots and nanowires. With further refinement, this method could eventually be used to integrate smart devices with living tissue for biomedical applications, such as bionics and biosensing.

…

An August 10, 2023 ACS news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, explains some of the issues with attaching electronics to living tissue,

Advances in electronics have enabled manufacturers to make integrated circuits and sensors with nanoscale resolution. More recently, laser printing and other techniques have made it possible to assemble flexible devices that can mold to curved surfaces. But these processes often use harsh chemicals, high temperatures or pressure extremes that are incompatible with living cells. Other methods are too slow or have poor spatial resolution. To avoid these drawbacks, David Gracias, Luo Gu and colleagues wanted to develop a nontoxic, high-resolution, lithographic method to attach nanomaterials to living tissue and cells.

The team used nanoimprint lithography to print a pattern of nanoscale gold lines or dots on a polymer-coated silicon wafer. The polymer was then dissolved to free the gold nanoarray so it could be transferred to a thin piece of glass. Next, the gold was functionalized with cysteamine and covered with a hydrogel layer, which, when peeled away, removed the array from the glass. The patterned side of this flexible array/hydrogel layer was coated with gelatin and attached to individual live fibroblast cells. In the final step, the hydrogel was degraded to expose the gold pattern on the surface of the cells. The researchers used similar techniques to apply gold nanoarrays to sheets of fibroblasts or to rat brains. Experiments showed that the arrays were biocompatible and could guide cell orientation and migration.

The researchers say their cost-effective approach could be used to attach other nanoscale components, such as electrodes, antennas and circuits, to hydrogels or living organisms, thereby opening up opportunities for the development of biohybrid materials, bionic devices and biosensors.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Institute on Aging, the National Science Foundation and the Johns Hopkins University Surpass Program.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Toward Single Cell Tattoos: Biotransfer Printing of Lithographic Gold Nanopatterns on Live Cells by Kam Sang Kwok, Yi Zuo, Soo Jin Choi, Gayatri J. Pahapale, Luo Gu, and David H. Gracias. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 16, 7477–7484 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c01960 Publication Date:August 1, 2023 Copyright © 2023 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.