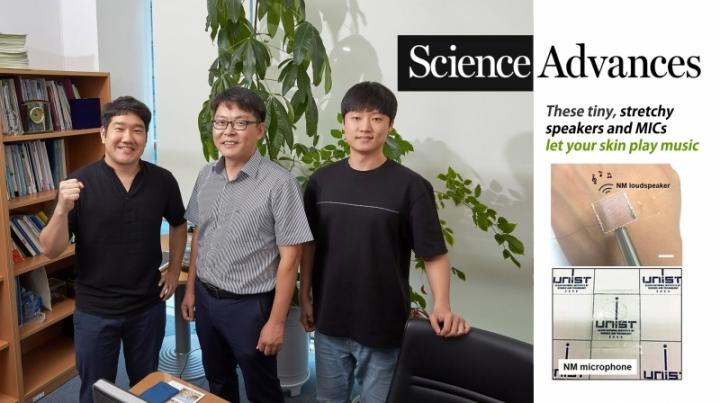

Caption: From left are Saewon Kang, Professor Hyunhyub Ko, and Seungse Cho in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST. Credit: UNIST

What are these scientists so happy about? A September 18, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily reveals all,

An international team of researchers, affiliated with UNIST [Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology] has presented an innovative wearable technology that will turn your skin into a loudspeaker.

An August 6, 2018 UNIST press release (also on EurekAlert but published September 17,2018), which originated the news item, delves further into the research,

This breakthrough has been led by Professor Hyunhyub Ko in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST. Created in part to help the hearing and speech impaired, the new technology can be further explored for various potential applications, such as wearable IoT sensors and conformal health care devices.

In the study, the research team has developed ultrathin, transparent, and conductive hybrid nanomembranes with nanoscale thickness, consisting of an orthogonal silver nanowire array embedded in a polymer matrix. They, then, demonstrated their nanomembrane by making it into a loudspeaker that can be attached to almost anything to produce sounds. The researchers also introduced a similar device, acting as a microphone, which can be connected to smartphones and computers to unlock voice-activated security systems.

Nanomembranes (NMs) are molcularly thin seperation layers with nanoscale thickness. Polymer NMs have attracted considerable attention owing to their outstanding advantages, such as extreme flexibility, ultralight weight, and excellent adhesibility in that they can be attached directly to almost any surface. However, they tear easily and exhibit no electrical conductivity.

The research team has solved such issues by embedding a silver nanowire network within a polymer-based nanomembrane. This has enabled the demonstration of skin-attachable and imperceptible loudspeaker and microphone.

“Our ultrathin, transparent, and conductive hybrid NMs facilitate conformal contact with curvilinear and dynamic surfaces without any cracking or rupture,” says Saewon Kang in the doctroral program of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST, the first author of the study.

He adds, “These layers are capable of detecting sounds and vocal vibrations produced by the triboelectric voltage signals corresponding to sounds, which could be further explored for various potential applications, such as sound input/output devices.”

Using the hybrid NMs, the research team fabricated skin-attachable NM loudspeakers and microphones, which would be unobtrusive in appearance because of their excellent transparency and conformal contact capability. These wearable speakers and microphones are paper-thin, yet still capable of conducting sound signals.

“The biggest breakthrough of our research is the development of ultrathin, transparent, and conductive hybrid nanomembranes with nanoscale thickness, less than 100 nanometers,” says Professor Ko. “These outstanding optical, electrical, and mechanical properties of nanomembranes enable the demonstration of skin-attachable and imperceptible loudspeaker and microphone.”The skin-attachable NM loudspeakers work by emitting thermoacoustic sound by the temperature-induced oscillation of the surrounding air. The periodic Joule heating that occurs when an electric current passes through a conductor and produces heat leads to these temperature oscillations. It has attracted considerable attention for being a stretchable, transparent, and skin-attachable loudspeaker.

Wearable microphones are sensors, attached to a speaker’s neck to even sense the vibration of the vocal folds. This sensor operates by converting the frictional force generated by the oscillation of the transparent conductive nanofiber into electric energy. For the operation of the microphone, the hybrid nanomembrane is inserted between elastic films with tiny patterns to precisely detect the sound and the vibration of the vocal cords based on a triboelectric voltage that results from the contact with the elastic films.

“For the commercial applications, the mechanical durability of nanomebranes and the performance of loudspeaker and microphone should be improved further,” says Professor Ko.

Thankfully, the researchers have made video that lets us hear this sound speaker,

Paper-thin stick-on speakers, developed by Professor Hyunhyub Ko and his research team at UNIST.

Thank you to the folks at UNIST for including something with the sound. Strangely, it’s not common practice to include audio when publishing research on sound, not in my experience anyway..

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Transparent and conductive nanomembranes with orthogonal silver nanowire arrays for skin-attachable loudspeakers and microphones by Saewon Kang, Seungse Cho, Ravi Shanker, Hochan Lee, Jonghwa Park, Doo-Seung Um, Youngoh Lee, and Hyunhyub Ko. Science Advances 03 Aug 2018: Vol. 4, no. 8, eaas8772 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aas8772

This paper appears to be open access.