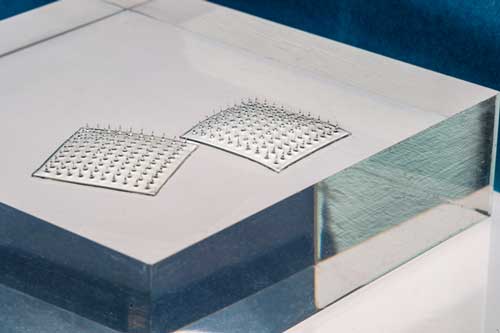

These sensors really do look like velcro,

A September 9, 2020 news item on Nanowerk announces some research from the Massachusetts Institute (MIT),

MIT engineers have designed a Velcro-like food sensor, made from an array of silk microneedles, that pierces through plastic packaging to sample food for signs of spoilage and bacterial contamination.

The sensor’s microneedles are molded from a solution of edible proteins found in silk cocoons, and are designed to draw fluid into the back of the sensor, which is printed with two types of specialized ink. One of these “bioinks” changes color when in contact with fluid of a certain pH range, indicating that the food has spoiled; the other turns color when it senses contaminating bacteria such as pathogenic E. coli.

…

A Sept. 9, 2020 MIT news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further into the research,

The researchers attached the sensor to a fillet of raw fish that they had injected with a solution contaminated with E. coli. After less than a day, they found that the part of the sensor that was printed with bacteria-sensing bioink turned from blue to red — a clear sign that the fish was contaminated. After a few more hours, the pH-sensitive bioink also changed color, signaling that the fish had also spoiled.

The results, published today in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, are a first step toward developing a new colorimetric sensor that can detect signs of food spoilage and contamination.

Such smart food sensors might help head off outbreaks such as the recent salmonella contamination in onions and peaches. They could also prevent consumers from throwing out food that may be past a printed expiration date, but is in fact still consumable.

“There is a lot of food that’s wasted due to lack of proper labeling, and we’re throwing food away without even knowing if it’s spoiled or not,” says Benedetto Marelli, the Paul M. Cook Career Development Assistant Professor in MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “People also waste a lot of food after outbreaks, because they’re not sure if the food is actually contaminated or not. A technology like this would give confidence to the end user to not waste food.”

Marelli’s co-authors on the paper are Doyoon Kim, Yunteng Cao, Dhanushkodi Mariappan, Michael S. Bono Jr., and A. John Hart.

Silk and printing

The new food sensor is the product of a collaboration between Marelli, whose lab harnesses the properties of silk to develop new technologies, and Hart, whose group develops new manufacturing processes.

Hart recently developed a high-resolution floxography technique, realizing microscopic patterns that can enable low-cost printed electronics and sensors. Meanwhile, Marelli had developed a silk-based microneedle stamp that penetrates and delivers nutrients to plants. In conversation, the researchers wondered whether their technologies could be paired to produce a printed food sensor that monitors food safety.

“Assessing the health of food by just measuring its surface is often not good enough. At some point, Benedetto mentioned his group’s microneedle work with plants, and we realized that we could combine our expertise to make a more effective sensor,” Hart recalls.

The team looked to create a sensor that could pierce through the surface of many types of food. The design they came up with consisted of an array of microneedles made from silk.

“Silk is completely edible, nontoxic, and can be used as a food ingredient, and it’s mechanically robust enough to penetrate through a large spectrum of tissue types, like meat, peaches, and lettuce,” Marelli says.

A deeper detection

To make the new sensor, Kim first made a solution of silk fibroin, a protein extracted from moth cocoons, and poured the solution into a silicone microneedle mold. After drying, he peeled away the resulting array of microneedles, each measuring about 1.6 millimeters long and 600 microns wide — about one-third the diameter of a spaghetti strand.

The team then developed solutions for two kinds of bioink — color-changing printable polymers that can be mixed with other sensing ingredients. In this case, the researchers mixed into one bioink an antibody that is sensitive to a molecule in E. coli. When the antibody comes in contact with that molecule, it changes shape and physically pushes on the surrounding polymer, which in turn changes the way the bioink absorbs light. In this way, the bioink can change color when it senses contaminating bacteria.

The researchers made a bioink containing antibodies sensitive to E. coli, and a second bioink sensitive to pH levels that are associated with spoilage. They printed the bacteria-sensing bioink on the surface of the microneedle array, in the pattern of the letter “E,” next to which they printed the pH-sensitive bioink, as a “C.” Both letters initially appeared blue in color.

Kim then embedded pores within each microneedle to increase the array’s ability to draw up fluid via capillary action. To test the new sensor, he bought several fillets of raw fish from a local grocery store and injected each fillet with a fluid containing either E. coli, Salmonella, or the fluid without any contaminants. He stuck a sensor into each fillet. Then, he waited.

After about 16 hours, the team observed that the “E” turned from blue to red, only in the fillet contaminated with E. coli, indicating that the sensor accurately detected the bacterial antigens. After several more hours, both the “C” and “E” in all samples turned red, indicating that every fillet had spoiled.

The researchers also found their new sensor indicates contamination and spoilage faster than existing sensors that only detect pathogens on the surface of foods.

“There are many cavities and holes in food where pathogens are embedded, and surface sensors cannot detect these,” Kim says. “So we have to plug in a bit deeper to improve the reliability of the detection. Using this piercing technique, we also don’t have to open a package to inspect food quality.”

The team is looking for ways to speed up the microneedles’ absorption of fluid, as well as the bioinks’ sensing of contaminants. Once the design is optimized, they envision the sensor could be used at various stages along the supply chain, from operators in processing plants, who can use the sensors to monitor products before they are shipped out, to consumers who may choose to apply the sensors on certain foods to make sure they are safe to eat.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Microneedle Technology for Sampling and Sensing Bacteria in the Food Supply Chain by Doyoon Kim, Yunteng Cao, Dhanushkodi Mariappan, Michael S. Bono Jr., A. John Hart, Benedetto Marelli. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202005370 First published: 09 September 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.