It took over a year after announcing the ‘Atoms to Product’ program in 2014 for DARPA (US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) to select 10 proponents for three projects. Before moving onto the latest announcement, here’s a description of the ‘Atoms to Product’ program from its Aug. 27, 2014 announcement on Nanowerk,

Many common materials exhibit different and potentially useful characteristics when fabricated at extremely small scales—that is, at dimensions near the size of atoms, or a few ten-billionths of a meter. These “atomic scale” or “nanoscale” properties include quantized electrical characteristics, glueless adhesion, rapid temperature changes, and tunable light absorption and scattering that, if available in human-scale products and systems, could offer potentially revolutionary defense and commercial capabilities. Two as-yet insurmountable technical challenges, however, stand in the way: Lack of knowledge of how to retain nanoscale properties in materials at larger scales, and lack of assembly capabilities for items between nanoscale and 100 microns—slightly wider than a human hair.

DARPA has created the Atoms to Product (A2P) program to help overcome these challenges. The program seeks to develop enhanced technologies for assembling atomic-scale pieces. It also seeks to integrate these components into materials and systems from nanoscale up to product scale in ways that preserve and exploit distinctive nanoscale properties.

DARPA’s Atoms to Product (A2P) program seeks to develop enhanced technologies for assembling nanoscale items, and integrating these components into materials and systems from nanoscale up to product scale in ways that preserve and exploit distinctive nanoscale properties.

A Dec. 29, 2015 news item on Nanowerk features the latest about the project,

DARPA recently selected 10 performers to tackle this challenge: Zyvex Labs, Richardson, Texas; SRI, Menlo Park, California; Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts; University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana; HRL Laboratories, Malibu, California; PARC, Palo Alto, California; Embody, Norfolk, Virginia; Voxtel, Beaverton, Oregon; Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Draper Laboratory, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

A Dec. 29, 2015 DARPA news release, which originated the news item, offers more information and an image illustrating the type of advances already made by one of the successful proponents,

DARPA recently launched its Atoms to Product (A2P) program, with the goal of developing technologies and processes to assemble nanometer-scale pieces—whose dimensions are near the size of atoms—into systems, components, or materials that are at least millimeter-scale in size. At the heart of that goal was a frustrating reality: Many common materials, when fabricated at nanometer-scale, exhibit unique and attractive “atomic-scale” behaviors including quantized current-voltage behavior, dramatically lower melting points and significantly higher specific heats—but they tend to lose these potentially beneficial traits when they are manufactured at larger “product-scale” dimensions, typically on the order of a few centimeters, for integration into devices and systems.

…

“The ability to assemble atomic-scale pieces into practical components and products is the key to unlocking the full potential of micromachines,” said John Main, DARPA program manager. “The DARPA Atoms to Product Program aims to bring the benefits of microelectronic-style miniaturization to systems and products that combine mechanical, electrical, and chemical processes.”

The program calls for closing the assembly gap in two steps: From atoms to microns and from microns to millimeters. Performers are tasked with addressing one or both of these steps and have been assigned to one of three working groups, each with a distinct focus area.

…

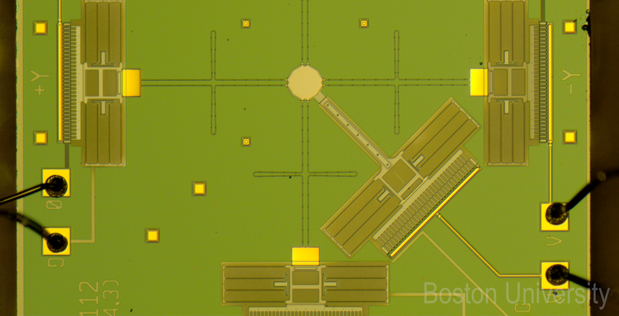

Image caption: Microscopic tools such as this nanoscale “atom writer” can be used to fabricate minuscule light-manipulating structures on surfaces. DARPA has selected 10 performers for its Atoms to Product (A2P) program whose goal is to develop technologies and processes to assemble nanometer-scale pieces—whose dimensions are near the size of atoms—into systems, components, or materials that are at least millimeter-scale in size. (Image credit: Boston University)

Here’s more about the projects and the performers (proponents) from the A2P performers page on the DARPA website,

Nanometer to Millimeter in a Single System – Embody, Draper and Voxtel

Current methods to treat ligament injuries in warfighters [also known as, soldiers]—which account for a significant portion of reported injuries—often fail to restore pre-injury performance, due to surgical complexities and an inadequate supply of donor tissue. Embody is developing reinforced collagen nanofibers that mimic natural ligaments and replicate the biological and biomechanical properties of native tissue. Embody aims to create a new standard of care and restore pre-injury performance for warfighters and sports injury patients at a 50% reduction compared to current costs.

Radio Frequency (RF) systems (e.g., cell phones, GPS) have performance limits due to alternating current loss. In lower frequency power systems this is addressed by braiding the wires, but this is not currently possibly in cell phones due to an inability to manufacture sufficiently small braided wires. Draper is developing submicron wires that can be braided using DNA self-assembly methods. If successful, portable RF systems will be more power efficient and able to send 10 times more information in a given channel.

For seamless control of structures, physics and surface chemistry—from the atomic-level to the meter-level—Voxtel Inc. and partner Oregon State University are developing an efficient, high-rate, fluid-based manufacturing process designed to imitate nature’s ability to manufacture complex multimaterial products across scales. Historically, challenges relating to the cost of atomic-level control, production speed, and printing capability have been effectively insurmountable. This team’s new process will combine synthesis and delivery of materials into a massively parallel inkjet operation that draws from nature to achieve a DNA-like mediated assembly. The goal is to assemble complex, 3-D multimaterial mixed organic and inorganic products quickly and cost-effectively—directly from atoms.

Optical Metamaterial Assembly – Boston University, University of Notre Dame, HRL and PARC.

Nanoscale devices have demonstrated nearly unlimited power and functionality, but there hasn’t been a general- purpose, high-volume, low-cost method for building them. Boston University is developing an atomic calligraphy technique that can spray paint atoms with nanometer precision to build tunable optical metamaterials for the photonic battlefield. If successful, this capability could enhance the survivability of a wide range of military platforms, providing advanced camouflage and other optical illusions in the visual range much as stealth technology has enabled in the radar range.

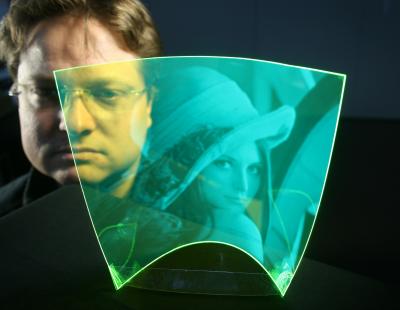

The University of Notre Dame is developing massively parallel nanomanufacturing strategies to overcome the requirement today that most optical metamaterials must be fabricated in “one-off” operations. The Notre Dame project aims to design and build optical metamaterials that can be reconfigured to rapidly provide on-demand, customized optical capabilities. The aim is to use holographic traps to produce optical “tiles” that can be assembled into a myriad of functional forms and further customized by single-atom electrochemistry. Integrating these materials on surfaces and within devices could provide both warfighters and platforms with transformational survivability.

HRL Laboratories is working on a fast, scalable and material-agnostic process for improving infrared (IR) reflectivity of materials. Current IR-reflective materials have limited use, because reflectivity is highly dependent on the specific angle at which light hits the material. HRL is developing a technique for allowing tailorable infrared reflectivity across a variety of materials. If successful, the process will enable manufacturable materials with up to 98% IR reflectivity at all incident angles.

PARC is working on building the first digital MicroAssembly Printer, where the “inks” are micrometer-size particles and the “image” outputs are centimeter-scale and larger assemblies. The goal is to print smart materials with the throughput and cost of laser printers, but with the precision and functionality of nanotechnology. If successful, the printer would enable the short-run production of large, engineered, customized microstructures, such as metamaterials with unique responses for secure communications, surveillance and electronic warfare.

Flexible, General Purpose Assembly – Zyvex, SRI, and Harvard.

Zyvex aims to create nano-functional micron-scale devices using customizable and scalable manufacturing that is top-down and atomically precise. These high-performance electronic, optical, and nano-mechanical components would be assembled by SRI micro-robots into fully-functional devices and sub-systems such as ultra-sensitive sensors for threat detection, quantum communication devices, and atomic clocks the size of a grain of sand.

SRI’s Levitated Microfactories will seek to combine the precision of MEMS [micro-electromechanical systems] flexures with the versatility and range of pick-and-place robots and the scalability of swarms [an idea Michael Crichton used in his 2002 novel Prey to induce horror] to assemble and electrically connect micron and millimeter components to build stronger materials, faster electronics, and better sensors.

Many high-impact, minimally invasive surgical techniques are currently performed only by elite surgeons due to the lack of tactile feedback at such small scales relative to what is experienced during conventional surgical procedures. Harvard is developing a new manufacturing paradigm for millimeter-scale surgical tools using low-cost 2D layer-by-layer processes and assembly by folding, resulting in arbitrarily complex meso-scale 3D devices. The goal is for these novel tools to restore the necessary tactile feedback and thereby nurture a new degree of dexterity to perform otherwise demanding micro- and minimally invasive surgeries, and thus expand the availability of life-saving procedures.

Sidebar

‘Sidebar’ is my way of indicating these comments have little to do with the matter at hand but could be interesting factoids for you.

First, Zyvex Labs was last mentioned here in a Sept. 10, 2014 posting titled: OCSiAL will not be acquiring Zyvex. Notice that this announcement was made shortly after DARPA’s A2P program was announced and that OCSiAL is one of RUSNANO’s (a Russian funding agency focused on nanotechnology) portfolio companies (see my Oct. 23, 2015 posting for more).

HRL Laboratories, mentioned here in an April 19, 2012 posting mostly concerned with memristors (nanoscale devices that mimic neural or synaptic plasticity), has its roots in Howard Hughes’s research laboratories as noted in the posting. In 2012, HRL was involved in another DARPA project, SyNAPSE.

Finally and minimally, PARC also known as, Xerox PARC, was made famous by Steven Jobs and Steve Wozniak when they set up their own company (Apple) basing their products on innovations that PARC had rejected. There are other versions of the story and one by Malcolm Gladwell for the New Yorker May 16, 2011 issue which presents a more complicated and, at times, contradictory version of that particular ‘origins’ story.