Scientists at Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois) and the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) have developed what could be a more sustainable way to produce electricity. From a July 31, 2019 news item on Nanowerk,

Scientists from Northwestern University and Caltech have produced electricity by simply flowing water over extremely thin layers of inexpensive metals, including iron, that have oxidized. These films represent an entirely new way of generating electricity and could be used to develop new forms of sustainable power production.

…

A July 31, 2019 Northwester University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Megan Fellman, which originated the news item, provides details that suggest this discovery could prove beneficial in medical implants, as well as, in solar cells,

The films have a conducting metal nanolayer (10 to 20 nanometers thick) that is insulated with an oxide layer (2 nanometers thick). Current is generated when pulses of rainwater and ocean water alternate and move across the nanolayers. The difference in salinity drags the electrons along in the metal below.

“It’s the oxide layer over the nanometal that really makes this device go,” said Franz M. Geiger, the Dow Professor of Chemistry in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. “Instead of corrosion, the presence of the oxides on the right metals leads to a mechanism that shuttles electrons.”

The films are transparent, a feature that could be taken advantage of in solar cells. The researchers intend to study the method using other ionic liquids, including blood. Developments in this area could lead to use in stents and other implantable devices.

“The ease of scaling up the metal nanolayer to large areas and the ease with which plastics can be coated gets us to three-dimensional structures where large volumes of liquids can be used,” Geiger said. “Foldable designs that fit, for instance, into a backpack are a possibility as well. Given how transparent the films are, it’s exciting to think about coupling the metal nanolayers to a solar cell or coating the outside of building windows with metal nanolayers to obtain energy when it rains.”

The study, titled “Energy Conversion via Metal Nanolayers,” was published this week [on July 29, 2019] in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

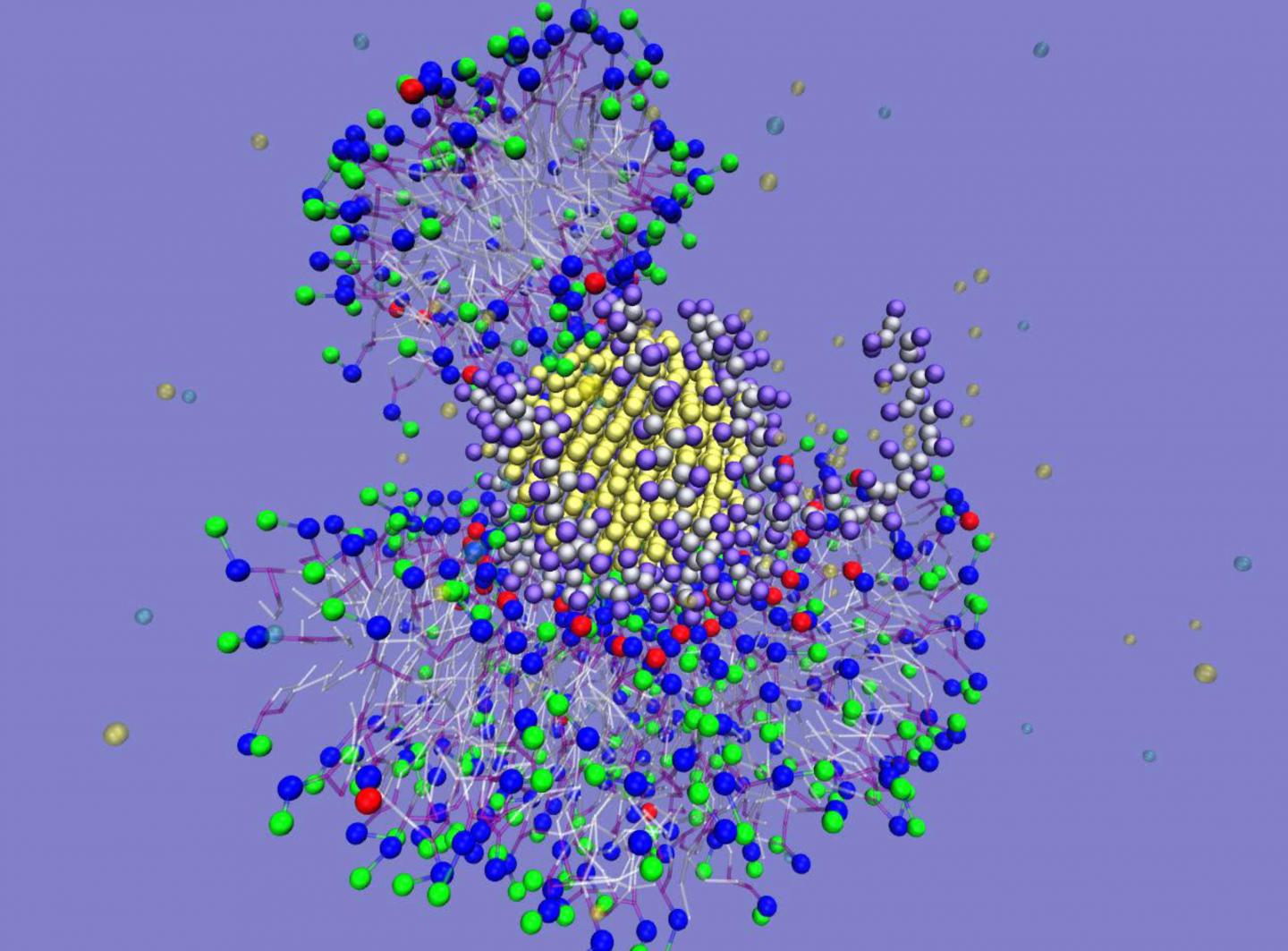

Geiger is the study’s corresponding author; his Northwestern team conducted the experiments. Co-author Thomas Miller, professor of chemistry at Caltech, led a team that conducted atomistic simulations to study the device’s behavior at the atomic level.

The new method produces voltages and currents comparable to graphene-based devices reported to have efficiencies of around 30% — similar to other approaches under investigation (carbon nanotubes and graphene) but with a single-step fabrication from earth-abundant elements instead of multistep fabrication. This simplicity allows for scalability, rapid implementation and low cost. Northwestern has filed for a provisional patent.

Of the metals studied, the researchers found that iron, nickel and vanadium worked best. They tested a pure rust sample as a control experiment; it did not produce a current.

The mechanism behind the electricity generation is complex, involving ion adsorption and desorption, but it essentially works like this: The ions present in the rainwater/saltwater attract electrons in the metal beneath the oxide layer; as the water flows, so do those ions, and through that attractive force, they drag the electrons in the metal along with them, generating an electrical current.

“There are interesting prospects for a variety of energy and sustainability applications, but the real value is the new mechanism of oxide-metal electron transfer,” Geiger said. “The underlying mechanism appears to involve various oxidation states.”

The team used a process called physical vapor deposition (PVD), which turns normally solid materials into a vapor that condenses on a desired surface. PVD allowed them to deposit onto glass metal layers only 10 to 20 nanometers thick. An oxide layer then forms spontaneously in air. It grows to a thickness of 2 nanometers and then stops growing.

“Thicker films of metal don’t succeed — it’s a nano-confinement effect,” Geiger said. “We have discovered the sweet spot.”

When tested, the devices generated several tens of millivolts and several microamps per centimeter squared.

“For perspective, plates having an area of 10 square meters each would generate a few kilowatts per hour — enough for a standard U.S. home,” Miller said. “Of course, less demanding applications, including low-power devices in remote locations, are more promising in the near term.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Energy conversion via metal nanolayers by Mavis D. Boamah, Emilie H. Lozier, Jeongmin Kim, Paul E. Ohno, Catherine E. Walker, Thomas F. Miller III, and Franz M. Geiger. PNAS DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906601116 First published July 29, 2019

This paper is behind a paywall.