Another day, another 2D material. A March 9, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily announced the latest thin material from Rice university,

Scientists at Rice University and the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, have discovered a method to make atomically flat gallium that shows promise for nanoscale electronics.

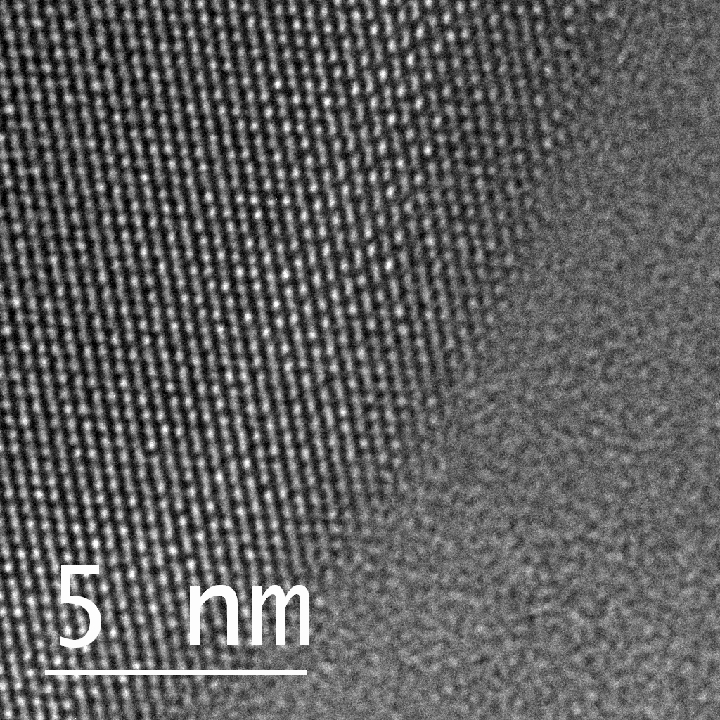

The Rice lab of materials scientist Pulickel Ajayan and colleagues in India created two-dimensional gallenene, a thin film of conductive material that is to gallium what graphene is to carbon.

Extracted into a two-dimensional form, the novel material appears to have an affinity for binding with semiconductors like silicon and could make an efficient metal contact in two-dimensional electronic devices, the researchers said.

A March 9, 2018 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the process for creating gallenene,

Gallium is a metal with a low melting point; unlike graphene and many other 2-D structures, it cannot yet be grown with vapor phase deposition methods. Moreover, gallium also has a tendency to oxidize quickly. And while early samples of graphene were removed from graphite with adhesive tape, the bonds between gallium layers are too strong for such a simple approach.

So the Rice team led by co-authors Vidya Kochat, a former postdoctoral researcher at Rice, and Atanu Samanta, a student at the Indian Institute of Science, used heat instead of force.

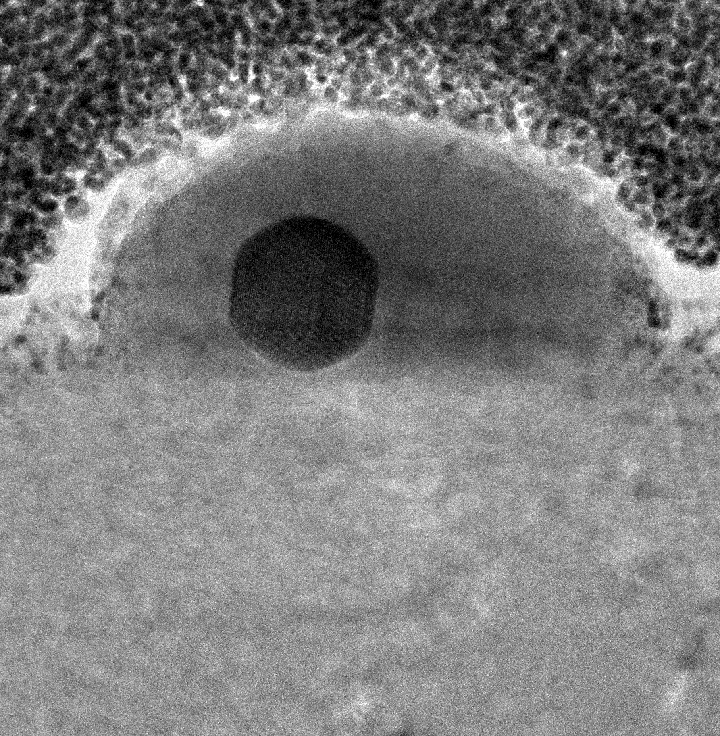

Rather than a bottom-up approach, the researchers worked their way down from bulk gallium by heating it to 29.7 degrees Celsius (about 85 degrees Fahrenheit), just below the element’s melting point. That was enough to drip gallium onto a glass slide. As a drop cooled just a bit, the researchers pressed a flat piece of silicon dioxide on top to lift just a few flat layers of gallenene.

They successfully exfoliated gallenene onto other substrates, including gallium nitride, gallium arsenide, silicone and nickel. That allowed them to confirm that particular gallenene-substrate combinations have different electronic properties and to suggest that these properties can be tuned for applications.

“The current work utilizes the weak interfaces of solids and liquids to separate thin 2-D sheets of gallium,” said Chandra Sekhar Tiwary, principal investigator on the project he completed at Rice before becoming an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Technology in Gandhinagar, India. “The same method can be explored for other metals and compounds with low melting points.”

Gallenene’s plasmonic and other properties are being investigated, according to Ajayan. “Near 2-D metals are difficult to extract, since these are mostly high-strength, nonlayered structures, so gallenene is an exception that could bridge the need for metals in the 2-D world,” he said.

Co-authors of the paper are graduate student Yuan Zhang and Associate Research Professor Robert Vajtai of Rice; Anthony Stender, a former Rice postdoctoral researcher and now an assistant professor at Ohio University; Sanjit Bhowmick, Praveena Manimunda and Syed Asif of Bruker Nano Surfaces, Minneapolis; and Rice alumnus Abhishek Singh of the Indian Institute of Science. Ajayan is chair of Rice’s Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering, the Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor in Engineering and a professor of chemistry.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research sponsored the research, with additional support from the Indo-US Science and Technology Forum, the government of India and a Rice Center for Quantum Materials/Smalley-Curl Postdoctoral Fellowship in Quantum Materials.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Atomically thin gallium layers from solid-melt exfoliation by Vidya Kochat, Atanu Samanta, Yuan Zhang, Sanjit Bhowmick, Praveena Manimunda, Syed Asif S. Asif, Anthony S. Stender, Robert Vajtai, Abhishek K. Singh, Chandra S. Tiwary, and Pulickel M. Ajayan. Science Advances 09 Mar 2018: Vol. 4, no. 3, e1701373 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1701373

This paper appears to be open access.