I meant to get this piece published sooner but good intentions don’t get you far.

At Northwestern University, scientists have researched the impact engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) might have as they enter the food chain. An October 18, 2019 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Megan Fellman describes research on an investigation of ENPs and their interaction with living organisms,

Personal electronic devices — smartphones, computers, TVs, tablets, screens of all kinds — are a significant and growing source of the world’s electronic waste. Many of these products use nanomaterials, but little is known about how these modern materials and their tiny particles interact with the environment and living things.

Now a research team of Northwestern University chemists and colleagues from the national Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology has discovered that when certain coated nanoparticles interact with living organisms it results in new properties that cause the nanoparticles to become sticky. Fragmented lipid coronas form on the particles, causing them to stick together and grow into long kelp-like strands. Nanoparticles with 5-nanometer diameters form long structures that are microns in size in solution. The impact on cells is not known.

“Why not make a particle that is benign from the beginning?” said Franz M. Geiger, professor of chemistry in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. He led the Northwestern portion of the research.

“This study provides insight into the molecular mechanisms by which nanoparticles interact with biological systems,” Geiger said. “This may help us understand and predict why some nanomaterial/ligand coating combinations are detrimental to cellular organisms while others are not. We can use this to engineer nanoparticles that are benign by design.”

Using experiments and computer simulations, the research team studied how gold nanoparticles wrapped in strings having positively charged beads interact with a variety of bilayer membrane models. The researchers found that a nearly circular layer of lipids forms spontaneously around the particles. Formation of these “fragmented lipid coronas” have never been seen before to form from membranes.

The study points to solving problems with chemistry. Scientists can use the findings to design a better ligand coating for nanoparticles that avoids the ammonium-phosphate interaction, which causes the aggregation. (Ligands are used in nanomaterials for layering.)

The results will be published Oct. 18 [2018] in the journal Chem.

Geiger is the study’s corresponding author. Other authors include scientists from the Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology’s other institutional partners. Based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the center studies engineered nanomaterials and their interaction with the environment, including biological systems — both the negative and positive aspects.

“The nanoparticles pick up parts of the lipid cellular membrane like a snowball rolling in a snowfield, and they become sticky,” Geiger said. “This unintended effect happens because of the presence of the nanoparticle. It can bring lipids to places in cells where lipids are not meant to be.”

The experiments were conducted in idealized laboratory settings that nevertheless are relevant to environments found during the late summer in a landfill — at 21-22 degrees Celsius and a couple feet below ground, where soil and groundwater mix and the food chain begins.

By pairing spectroscopic and imaging experiments with atomistic and coarse-grain simulations, the researchers identified that ion pairing between the lipid head groups of biological membranes and the polycations’ ammonium groups in the nanoparticle wrapping leads to the formation of fragmented lipid coronas. These coronas engender new properties, including composition and stickiness, to the particles with diameters below 10 nanometers.

The study’s insights help predict the impact that the increasingly widespread use of engineered nanomaterials has on the nanoparticles’ fate once they enter the food chain, which many of them may eventually do.

“New technologies and mass consumer products are emerging that feature nanomaterials as critical operational components,” Geiger said. “We can upend the existing paradigm in nanomaterial production towards one in which companies design nanomaterials to be sustainable from the beginning, as opposed to risking expensive product recalls — or worse — down the road.” [emphases mine]

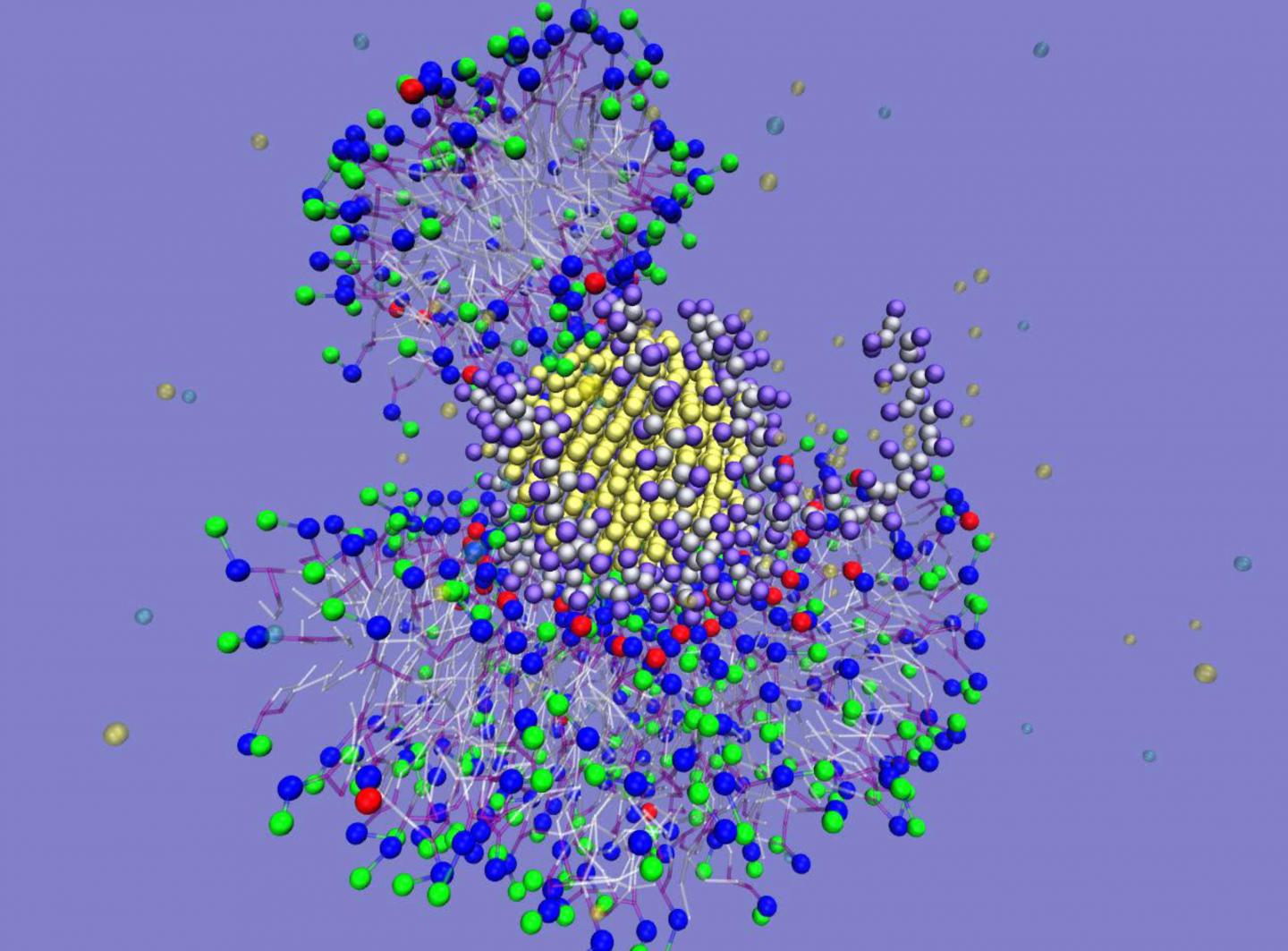

Here’s an image illustrating the work,

Caption: This is a computer simulation of a lipid corona around a 5-nanometer nanoparticle showing ammonium-phosphate ion pairing. Credit: Northwestern University

The curious can find the paper here,

Lipid Corona Formation from Nanoparticle Interactions with Bilayers by Laura L. Olenick, Julianne M. Troiano, Ariane Vartanian, Eric S. Melby, Arielle C. Mensch, Leili Zhang, Jiewei Hong, Oluwaseun Mesele, Tian Qiu, Jared Bozich, Samuel Lohse, Xi Zhang, Thomas R. Kuech, Augusto Millevolte, Ian Gunsolus, Alicia C. McGeachy, Merve Doğangün, Tianzhe Li, Dehong Hu, Stephanie R. Walter, Aurash Mohaimani, Angela Schmoldt, Marco D. Torelli, Katherine R. Hurley, Joe Dalluge, Gene Chong, Z. Vivian Feng, Christy L. Haynes, Robert J. Hamers, Joel A. Pedersen, Qiang Cui, Rigoberto Hernandez, Rebecca Klaper, Galya Orr, Catherine J. Murphy, Franz M. Geiger. Chem Volume 4, ISSUE 11, P2709-2723, November 08, 2018 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2018.09.018 Published:October 18, 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.