A June 17, 2014 news item on Nanowerk features a new approach to sensing gases from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT),

Using microscopic polymer light resonators that expand in the presence of specific gases, researchers at MIT’s Quantum Photonics Laboratory have developed new optical sensors with predicted detection levels in the parts-per-billion range. Optical sensors are ideal for detecting trace gas concentrations due to their high signal-to-noise ratio, compact, lightweight nature, and immunity to electromagnetic interference.

Although other optical gas sensors had been developed before, the MIT team conceived an extremely sensitive, compact way to detect vanishingly small amounts of target molecules.

A June 17, 2014 American Institute of Physics (AIP) news release by John Arnst, which originated the news item, describes the new technique in some detail,

The researchers fabricated wavelength-scale photonic crystal cavities from PMMA, an inexpensive and flexible polymer that swells when it comes into contact with a target gas. The polymer is infused with fluorescent dye, which emits selectively at the resonant wavelength of the cavity through a process called the Purcell effect. At this resonance, a specific color of light reflects back and forth a few thousand times before eventually leaking out. A spectral filter detects this small color shift, which can occur at even sub-nanometer level swelling of the cavity, and in turn reveals the gas concentration.

“These polymers are often used as coatings on other materials, so they’re abundant and safe to handle. Because of their deformation in response to biochemical substances, cavity sensors made entirely of this polymer lead to a sensor with faster response and much higher sensitivity,” said Hannah Clevenson. Clevenson is a PhD student in the electrical engineering and computer science department at MIT, who led the experimental effort in the lab of principal investigator Dirk Englund.

PMMA can be treated to interact specifically with a wide range of different target chemicals, making the MIT team’s sensor design highly versatile. There’s a wide range of potential applications for the sensor, said Clevenson, “from industrial sensing in large chemical plants for safety applications, to environmental sensing out in the field, to homeland security applications for detecting toxic gases, to medical settings, where the polymer could be treated for specific antibodies.”

…

The thin PMMA polymer films, which are 400 nanometers thick, are patterned with structures that are 8-10 micrometers long by 600 nanometers wide and suspended in the air. In one experiment, the films were embedded on tissue paper, which allowed 80 percent of the sensors to be suspended over the air gaps in the paper. Surrounding the PMMA film with air is important, Clevenson said, both because it allows the device to swell when exposed to the target gas, and because the optical properties of air allow the device to be designed to trap light travelling in the polymer film.

The team found that these sensors are easily reusable since the polymer shrinks back to its original length once the targeted gas has been removed.

The current experimental sensitivity of the devices is 10 parts per million, but the team predicts that with further refinement, they could detect gases with part-per-billion concentration levels.

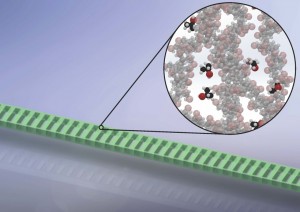

The researchers have provided an image illustrating the sensor’s response to a target gas,

High-sensitivity detection of dilute gases is demonstrated by monitoring the resonance of a suspended polymer nanocavity. The inset shows the target gas molecules (darker) interacting with the polymer material (lighter). This interaction causes the nanocavity to swell, resulting in a shift of its resonance.

CREDIT: H. Clevenson/MIT

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

High sensitivity gas sensor based on high-Q suspended polymer photonic crystal nanocavity by Hannah Clevenson, Pierre Desjardins, Xuetao Gan, and Dirk Englund. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 241108 (2014); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4879735

This is an open access paper.