I have two news releases about this reseach, one from March 2023 focused on the technology and one from May 2023 focused on the graffiti.

Simon Fraser University (SFU) and the technology

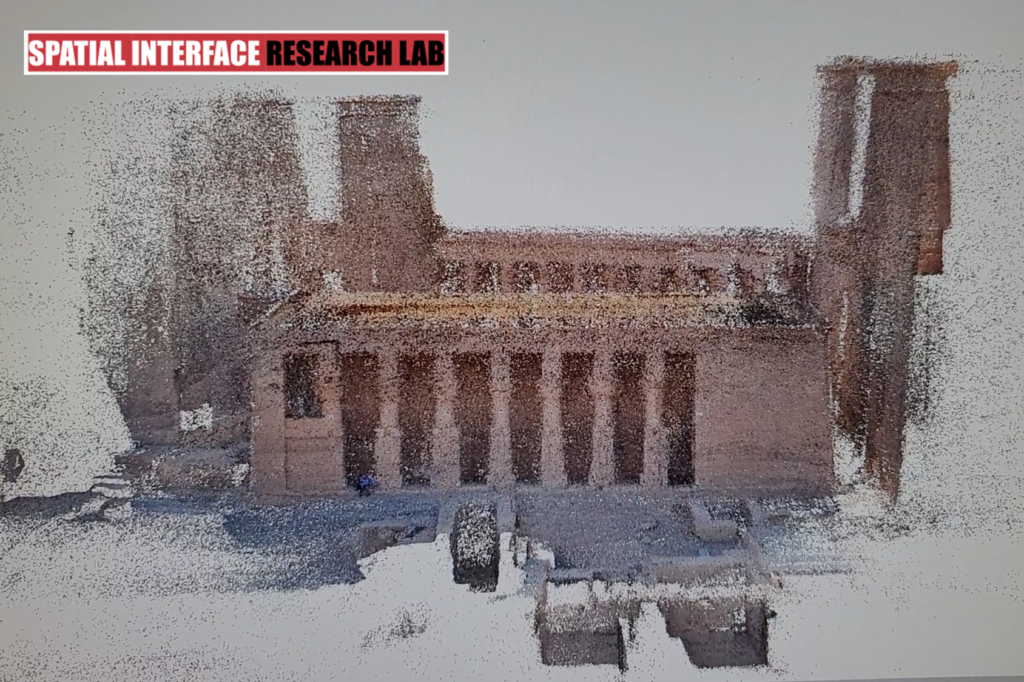

While this looks like an impressionist painting (to me), I believe it’s a still from the spatial reality capture of the temple the researchers were studying,

A March 30, 2023 news item on phys.org announces the latest technology for research on Egyptian graffiti (Note: A link has been removed),

Simon Fraser University [SFU; Canada] researchers are learning more about ancient graffiti—and their intriguing comparisons to modern graffiti—as they produce a state-of-the-art 3D recording of the Temple of Isis in Philae, Egypt.

Working with the University of Ottawa, the researchers published their early findings in Egyptian Archaeology and have returned to Philae to advance the project.

“It’s fascinating because there are similarities with today’s graffiti,” says SFU geography professor Nick Hedley, co-investigator of the project. “The iconic architecture of ancient Egypt was built by those in positions of power and wealth, but the graffiti records the voices and activities of everybody else. The building acts like a giant sponge or notepad for generations of people from different cultures for over 2,000 years.”

…

A March 30, 2023 SFU news release (also on EurekAlert) by Courtney Lust, which originated the news item, provides more details about the technology,

As an expert in spatial reality capture, Hedley leads the team’s innovative visualization efforts, documenting the graffiti, their architectural context, and the spaces they are found in using advanced methods like photogrammetry, raking light, and laser scanning. “I’m recording reality in three-dimensions — the dimensionality in which it exists,” he explains.

With hundreds if not thousands of graffiti, some carved less than a millimeter deep on the temple’s columns, walls, and roof, precision is essential.

Typically, the graffiti would be recorded through a series of photographs — a step above hand-drawn documents — allowing researchers to take pieces of the site away and continue working.

Sabrina Higgins, an SFU archaeologist and project co-investigator, says photographs and two-dimensional plans do not allow the field site to be viewed as a dynamic, multi-layered, and evolving space. “The techniques we are applying to the project will completely change how the graffiti, and the temple, can be studied,” she says.

Hedley is moving beyond basic two-dimensional imaging to create a cutting-edge three-dimensional recording of the temple’s entire surface. This will allow the interior and exterior of the temple, and the graffiti, to be viewed and studied at otherwise impossible viewpoints, from virtually anywhere— without compromising detail.

This three-dimensional visualization will also enable researchers to study the relationship between a figural graffito, any graffiti that surrounds it, and its location in relation to the structure of temple architecture.

While this is transformative for viewing and studying the temple and its inscriptions, Hedley points to the big-picture potential of applying spatial reality capture technology to the field of archaeology, and beyond.

“Though my primary role in this project is to help build the definitive set of digital wall plans for the Mammisi at Philae, I’m also demonstrating how emerging spatial reality capture methods can fundamentally change how we gather and produce data and transform our ability to interpret and analyze these spaces. This is a space to watch!” says Hedley.

Did Hedley mean to make a pun with the comment used to end the news release? I hope so.

University of Ottawa and ancient Egyptian graffiti

A May 4, 2023 University of Ottawa news release by Isabelle Mailloux Pulkinghorn describes the graffiti end of things in more detail, Note: Links have been removed,

Egypt’s Philae temple complex is one of the country’s most famed archeological sites. It is dedicated to the goddess Isis, who was one of the most important deities in ancient Egyptian religion. The main temple is a stunning example of the country’s ancient architecture, with its towering columns and detailed carvings depicting Isis and other gods.

In a world-first,The Philae Temple Graffiti Project research team was able to digitally capture the temple’s graffiti by recording and studying a novel group of neglected evidence for personal religious piety dating to the Graeco-Roman and Late Antique periods. By using advanced recording techniques, like photogrammetry and laser scanning, researchers were able to create a photographic recording of the graffiti, digitizing them in 3D to fully capture their details and surroundings.

“This is not only the first study of circa 400 figural graffiti from one of the most famous temples in Egypt, the Isis temple at Philae,” explains project director Dr. Jitse H.F. Dijkstra, a professor of Classics in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Ottawa (uOttawa). “It is the first to use advanced, cutting-edge methods to record these signs of personal piety in an accurate manner and within their architectural context. This is digital humanities in action.”

Professor Dijkstra collaborates in the project with co-investigators Nicholas Hedley, a geography professor at Simon Fraser University (SFU), Sabrina Higgins, an archaeologist and art historian also at SFU, and Roxanne Bélanger Sarrazin, a uOttawa alumna, now a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Oslo.

Temple walls reveal their messages

The newly available state-of-the-art technology has allowed the team to uncover hundreds of 2,000-year-old figural graffiti (a type of graffito consisting of figures or images rather than symbols or text) on the Isis temple’s walls. They have also been able to study them from vantage points that would otherwise have been difficult to reach.

Today, graffiti are seen as an art form that serves as a means of communication, to mark a name or ‘tag,’ or to leave a reference to one’s presence at a given site. The 2,000-year-old graffiti of ancient civilisations served a similar purpose. The research team has found drawings – some carved only 1mm deep – of feet, animals, deities and other figures meant to express the personal religious piety of the maker in the temple complex.

Using 3D renderings of the interior and exterior of the temple, the team gained detailed knowledge about where the graffiti are found on the walls, and their meaning. Although the majority of the graffiti are intended to ask for divine protection, others were playful gameboards; Old Egyptian temples functioned as a focus of worship and more ephemeral activities.

A first for this UNESCO heritage site, the innovative fieldwork is at the forefront of Egyptian archaeology and digital humanities (which explores human interactions and culture).

“What ancient Egyptian graffiti have in common with modern graffiti is they are left in places not originally foreseen for that purpose,” adds Professor Dijkstra. “The big difference, however, is that ancient Egyptian graffiti were left by individuals at temples in order to receive divine protection forever, which is why we find hundreds of graffiti on every Egyptian temple’s walls.”

The Philae Temple Graffiti Project was initiated in 2016 under the aegis of the Philae Temple Text Project of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Swiss Institute for Architectural and Archaeological Research on Ancient Egypt, Cairo. It is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and aims to study the figural graffiti from one of the most spectacular temple complexes of Egypt, Philae, in order to better understand the daily practice of the goddess’ worship.

The study’s first findings were published in Egyptian Archeology

Fascinatingly for a project where new technology has been vital, the work has been published in a periodical (Egyptian Archaeology) that is not available online. It is published by the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) which also produces the similarly titled “Journal of Egyptian Archaeology”.

You can purchase the relevant issue of “Egyptian Archaeology” here. The EES describes it as a “… full-colour magazine, reporting on current excavations, surveys and research in Egypt and Sudan, showcasing the work of the EES as well as of other missions and researchers.”

Here’s a citation for the article,

Figures that Matter: Graffiti of the Isis Temple at Philae by Roxanne Bélanger Sarrazin, Jitse Dijkstra, Nicholas Hedley and Sabrina Higgins. Egyptian Archaeology, Spring 2022, [issue no.] 60.

![Stencil on the waterline of The Thekla, an entertainment boat in central Bristol – (wider view). The section of the hull with this picture has now been removed and is on display at the M Shed museum. The image of Death is based on a nineteenth-century etching illustrating the pestilence of The Great Stink.[19] Artist: Banksy - Photographed by Adrian Pingstone](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Banksy.jpg)