Let’s add a comment from a writer, notably William Gibson in an interview with the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) prior to the launch of his latest book, Zero History.

William Gibson in a Sept.6, 2010 interview with Steven Kurutz for the WSJ blog, Speakeasy,

Will you mourn the loss of the physical book if eBooks become the dominant format?

It doesn’t fill me with quite the degree of horror and sorrow that it seems to fill many of my friends. For one thing, I don’t think that physical books will cease to be produced. But the ecological impact of book manufacture and traditional book marketing –- I think that should really be considered. We have this industry in which we cut down trees to make the paper that we then use enormous amounts of electricity to turn into books that weigh a great deal and are then shipped enormous distances to point-of-sale retail. Often times they are remained or returned, using double the carbon footprint. And more electricity is used to pulp them and turn them into more books. If you look at it from a purely ecological point of view, it’s crazy.

Gibson goes on to suggest that the perfect scenario would feature bookstores displaying one copy of each book being offered for sale. Prospective readers would be able to view the book and purchase their own copy through a print-on-demand system. He does not speculate about any possible role for e-books.

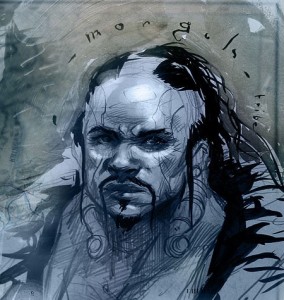

For a contrasting approach from writers, let’s take Neal Stephenson, Greg Bear and other members of the Mongoliad novel/project which is being written/conducted online. I’m inferring from the publicity and written material on the Mongoliad website that these writers, artists, and others are experimenting with new business and storytelling models in the face of a rapidly changing publishing and reading environment. I’ve posted about Mongoliad here (Sept.7,2010) and here (May 31,2010).

Edward Picot at The Hyperliterature Exchange has written a substantive essay, It’s Literature Jim… but not as we know i: Publishing and the Digital Revolution, which explores this topic from the perspective of someone who’s been heavily involved in the debate for many years. From the Picot essay,

It seems we may finally be reaching the point where ebooks are going to pose a genuine challenge to print-and-paper. Amazon have just announced that Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has become the first ebook to sell more than a million copies; and also that they are now selling more copies of ebooks than books in hardcover. [emphasis mine]

As for more proof as to how much things are changing, the folks who produce the Oxford English Dictionary (the 20 volume version) have announced that the 1989 edition may have been the last print edition. From Dan Nosowitz’s article on the Fast Company website,

The Oxford English Dictionary, currently a 20 volume, 750-pound monstrosity, has been the authoritative word on the words of the English language for 126 years. The OED3, the first new edition since 1989, may also be the first to forgo print entirely, reports the AP.

…

Nigel Portwood, chief executive of the Oxford University Press (isn’t that the perfect name for him?), says online revenue has been so high that it is highly unlikely that the third edition of the OED will be physically printed. The full 20-volume set costs $995 at Amazon, and of course it requires supplementals regularly to account for valuable words like “bootylicious.”

Meanwhile the Shifted Librarian weighs in by comparing her Kindle experience with a print book in a September 7, 2010 posting,

I knew my desire to share content was the prime driver of the format I was choosing, but I didn’t realize how quickly it was shifting in the opposite direction. I now want to share one-to-many, not one-to-one, and I just don’t have the time or resources to transcribe everything I want to share. It makes me sad to look at that long list of print books I’ve read over the past year that I likely won’t share here because I can’t copy and paste.

Jenny (The Shifted Librarian) ends her essay with this,

Of course, your mileage may vary, but I think I’ve finally crossed over to the ebook side. I’ll have to go to bookstores and the library just to touch new books for old time’s sake. Only time will tell if there’s a “feature” of print books that can draw me back. My reasons for converting are definitely an edge case, and I haven’t been a heavy user of print resources in libraries in quite some time, but I can’t help but wonder how this type of shift will affect libraries. I see more and more ereaders on my commute every day.

I was on the bus today and was struck by how many people were reading books and newspapers but I’m not drawing any serious conclusions from my informal survey. I think the lack of e-books, tablets and their ilk may be a consequence of the Canadian market where we tend to get digital devices after they’ve been on the US market for a while and when we get them, we pay more.

Despite all the discussion about e-books and tablets, I think what it comes down to is whether or not people are going to continue reading and, if we do , whether we”ll be reading the same way. Personally, I think there’ll be less reading. After all, literacy isn’t a given and with more and more icons (e.g., signage in airports, pedestrian walk signals, your software programmes, etc.) taking the place that once was occupied by written words then, why would we need to learn to read? In the last year, I’ve seen science journal abstracts (which used to be text only) that are graphical, i.e., text illustrated with images. Plus there’s been a resurgence of radio online and other audio products (rap, spoken word poets, podcasts, etc.) which hints at a greater investment in oral culture in the future.

These occurrences and others suggest to me that a massive change is underway. If you need any more proof, there’s Arthur Sulzburger Jr.’s admission at the recent International Newsroom Summit held in London England (from the Sept.8, 2010 article by Steve Huff in the New York Observer Daily Transom),

During a talk at the International Newsroom Summit held in London, Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. admitted that “we will stop printing the New York Times sometime in the future,” but, said Sulzberger, that date is “TBD.”

In the foreseeable future, we might need to read (although we may find ourselves moving to a more orally-based culture) but not as extensively as before. We won’t spend quite as much time learning to read and will better use the training time to learn about such topics as physics or coding computers or something. Knowledge, scientific and otherwise, is going to be transmitted and received via many channels and I don’t believe that the written word will be as privileged as it is today.

In the meantime, there are any number of avenues for writers and readers to pursue. One that I find personally fascinating is the subculture of literary tattoos (from The Word Made Flesh [Thanks to @ruthseeley for tweeting about the website.]),

It says “It rained for four years, eleven months and two days.” in portuguese. The illustration and phrase are from “100 years of solitude” by G.G. Márquez. That book means a lot to me. This picture was takes the same day i got the tattoo, so it’s a little bloody. It was very cold that day.

Given that I live in an area known for its rainy weather, this particular tattoo was a no-brainer choice.