Sometimes it’s good to try and pull things together.

University of Glasgow and monitoring chronic conditions

A February 23, 2018 news item on phys.org describes the latest wearable tech from the University of Glasgow,

A new type of flexible, wearable sensor could help people with chronic conditions like diabetes avoid the discomfort of regular pin-prick blood tests by monitoring the chemical composition of their sweat instead.

In a new paper published in the journal Biosensors and Bioelectronics, a team of scientists from the University of Glasgow’s School of Engineering outline how they have built a stretchable, wireless system which is capable of measuring the pH level of users’ sweat.

A February 22, 2018 University of Glasgow press release, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

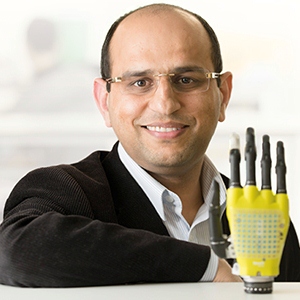

Courtesy: University of Glasgow

Sweat, like blood, contains chemicals generated in the human body, including glucose and urea. Monitoring the levels of those chemicals in sweat could help clinicians diagnose and monitor chronic conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease and some types of cancers without invasive tests which require blood to be drawn from patients.

However, non-invasive, wearable systems require consistent contact with skin to offer the highest-quality monitoring. Current systems are made from rigid materials, making it more difficult to ensure consistent contact, and other potential solutions such as adhesives can irritate skin. Wireless systems which use Bluetooth to transmit their information are also often bulky and power-hungry, requiring frequent recharging.

The University of Glasgow team’s new system is built around an inexpensively-produced sensor capable of measuring pH levels which can stretch and flex to better fit the contours of users’ bodies. Made from a graphite-polyurethane composite and measuring around a single square centimetre, it can stretch up to 53% in length without compromising performance. It will also continue to work after being subjected to flexes of 30% up to 500 times, which the researchers say will allow it to be used comfortably on human skin with minimal impact on the performance of the sensor.

The sensor can transmit its data wirelessly, and without external power, to an accompanying smartphone app called ‘SenseAble’, also developed by the team. The transmissions use near-field communication, a data transmission system found in many current smartphones which is used most often for smartphone payments like ApplePay, via a stretchable RFID antenna integrated into the system – another breakthrough innovation from the research team.

The smartphone app allows users to track pH levels in real time and was demonstrated in the lab using a chemical solution created by the researchers which mimics the composition of human sweat.

The research was led by Professor Ravinder Dahiya, head of the University of Glasgow’s School of Engineering’s Bendable Electronics and Sensing Technologies (BEST) group.

Professor Dahiya said: “Human sweat contains much of the same physiological information that blood does, and its use in diagnostic systems has the significant advantage of not needing to break the skin in order to administer tests.

“Now that we’ve demonstrated that our stretchable system can be used to monitor pH levels, we’ve already begun additional research to expand the capabilities of the sensor and make it a more complete diagnostic system. We’re planning to add sensors capable of measuring glucose, ammonia and urea, for example, and ultimately we’d like to see a system ready for market in the next few years.”

The team’s paper, titled ‘Stretchable Wireless System for Sweat pH Monitoring’, is published in Biosensors and Bioelectronics. The research was supported by funding from the European Commission and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Stretchable wireless system for sweat pH monitoring by Wenting Dang, Libu Manjakkal, William Taube Navaraj, Leandro Lorenzelli, Vincenzo Vinciguerra. Biosensors and Bioelectronics Volume 107, 1 June 2018, Pages 192–202 [Available online February 2018] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2018.02.025

This paper is behind a paywall.

University of British Columbia (UBC; Okanagan) and monitor bio-signals

This is a completely other type of wearable tech monitor, from a February 22, 2018 UBC news release (also on EurekAlert) by Patty Wellborn (A link has been removed),

Creating the perfect wearable device to monitor muscle movement, heart rate and other tiny bio-signals without breaking the bank has inspired scientists to look for a simpler and more affordable tool.

Now, a team of researchers at UBC’s Okanagan campus have developed a practical way to monitor and interpret human motion, in what may be the missing piece of the puzzle when it comes to wearable technology.

What started as research to create an ultra-stretchable sensor transformed into a sophisticated inter-disciplinary project resulting in a smart wearable device that is capable of sensing and understanding complex human motion, explains School of Engineering Professor Homayoun Najjaran.

The sensor is made by infusing graphene nano-flakes (GNF) into a rubber-like adhesive pad. Najjaran says they then tested the durability of the tiny sensor by stretching it to see if it can maintain accuracy under strains of up to 350 per cent of its original state. The device went through more than 10,000 cycles of stretching and relaxing while maintaining its electrical stability.

“We tested this sensor vigorously,” says Najjaran. “Not only did it maintain its form but more importantly it retained its sensory functionality. We have further demonstrated the efficacy of GNF-Pad as a haptic technology in real-time applications by precisely replicating the human finger gestures using a three-joint robotic finger.”

The goal was to make something that could stretch, be flexible and a reasonable size, and have the required sensitivity, performance, production cost, and robustness. Unlike an inertial measurement unit—an electronic unit that measures force and movement and is used in most step-based wearable technologies—Najjaran says the sensors need to be sensitive enough to respond to different and complex body motions. That includes infinitesimal movements like a heartbeat or a twitch of a finger, to large muscle movements from walking and running.

School of Engineering Professor and study co-author Mina Hoorfar says their results may help manufacturers create the next level of health monitoring and biomedical devices.

“We have introduced an easy and highly repeatable fabrication method to create a highly sensitive sensor with outstanding mechanical and electrical properties at a very low cost,” says Hoorfar.

To demonstrate its practicality, researchers built three wearable devices including a knee band, a wristband and a glove. The wristband monitored heartbeats by sensing the pulse of the artery. In an entirely different range of motion, the finger and knee bands monitored finger gestures and larger scale muscle movements during walking, running, sitting down and standing up. The results, says Hoorfar, indicate an inexpensive device that has a high-level of sensitivity, selectivity and durability.

Hoorfar and Najjaran are both members of the Okanagan node of UBC’s STITCH (SmarT Innovations for Technology Connected Health) Institute that creates and investigates advanced wearable devices.

The research, partially funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, was recently published in the Journal of Sensors and Actuators A: Physical.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Low-cost ultra-stretchable strain sensors for monitoring human motion and bio-signals by Seyed Reza Larimi, Hojatollah Rezaei Nejad, Michael Oyatsi, Allen O’Brien, Mina Hoorfar, Homayoun Najjaran. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical Volume 271, 1 March 2018, Pages 182-191 [Published online February 2018] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2018.01.028

This paper is behind a paywall.

Final comments

The term ‘wearable tech’ covers a lot of ground. In addition to sensors, there are materials that harvest energy, detect poisons, etc. making for a diverse field.