Mother-of-pearl (also known as nacre) research has been featured here a few times (links at the end of this post). This time it touches on self-assembly, which is the source of much interest and, on occasion, much concern in the field of nanotechnology.

In any case, the latest mother-of-pearl work comes from the Technische Universität (TU) Dresden (Technical University of Dresden), located in Germany. From a January 4, 2021 news item on phys.org,

In a new study published in Nature Physics, researchers from the B CUBE—Center for Molecular Bioengineering at TU Dresden and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble [Grance] describe, for the first time, that structural defects in self-assembling nacre attract and cancel each other out, eventually leading to a perfect periodic structure.

…

A January 4, 2021 Technische Universität (TU) Dresden press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, explains the reason for the ongoing interest in mother-of-pearl and reveals an unexpected turn in the research,

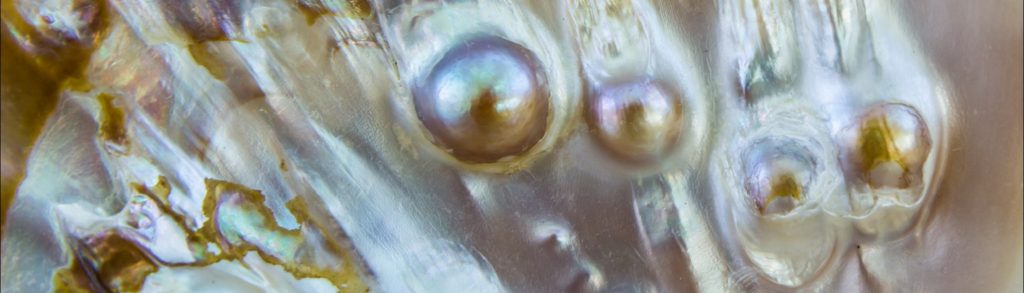

Mollusks build shells to protect their soft tissues from predators. Nacre, also known as the mother of pearl, has an intricate, highly regular structure that makes it an incredibly strong material. Depending on the species, nacres can reach tens of centimeters in length. No matter the size, each nacre is built from materials deposited by a multitude of single cells at multiple different locations at the same time. How exactly this highly periodic and uniform structure emerges from the initial disorder was unknown until now.

Nacre formation starts uncoordinated with the cells depositing the material simultaneously at different locations. Not surprisingly, the early nacre structure is not very regular. At this point, it is full of defects. “In the very beginning, the layered mineral-organic tissue is full of structural faults that propagate through a number of layers like a helix. In fact, they look like a spiral staircase, having either right-handed or left-handed orientation,” says Dr. Igor Zlotnikov, research group leader at the B CUBE – Center for Molecular Bioengineering at TU Dresden. “The role of these defects in forming such a periodic tissue has never been established. On the other hand, the mature nacre is defect-free, with a regular, uniform structure. How could perfection emerge from such disorder?”

The researchers from the Zlotnikov group collaborated with the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble to take a very detailed look at the internal structure of the early and mature nacre. Using synchrotron-based holographic X-ray nano-tomography the researchers could capture the growth of nacre over time. “Nacre is an extremely fine structure, having organic features below 50 nm in size. Beamline ID16A at the ESRF provided us with an unprecedented capability to visualize nacre in three-dimensions,” explains Dr. Zlotnikov. “The combination of electron dense and highly periodical inorganic platelets with delicate and slender organic interfaces makes nacre a challenging structure to image. Cryogenic imaging helped us to obtain the resolving power we needed,” explains Dr. ‘Alexandra] Pacureanu from the X-ray Nanoprobe group at the ESRF.

The analysis of data was quite a challenge. The researchers developed a segmentation algorithm using neural networks and trained it to separate different layers of nacre. In this way, they were able to follow what happens to the structural defects as nacre grows.

The behavior of structural defects in a growing nacre was surprising. Defects of opposite screw direction were attracted to each other from vast distances. The right-handed and left-handed defects moved through the structure, until they met, and cancelled each other out. These events led to a tissue-wide synchronization. Over time, it allowed the structure to develop into a perfectly regular and defect-free.

Periodic structures similar to nacre are produced by many different animal species. The researchers think that the newly discovered mechanism could drive not only the formation of nacre but also other biogenic structures.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Dynamics of topological defects and structural synchronization in a forming periodic tissue by Maksim Beliaev, Dana Zöllner, Alexandra Pacureanu, Paul Zaslansky & Igor Zlotnikov. Nature Physics (2021) First published online: 17 September 2020 Published: 04 January 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.

As promised here are the links for One tough mother, imitating mother-of-pearl for stronger ceramics (a March 14, 2014 posting) and Clues as to how mother of pearl is made (a December 15, 2015 posting).