This research approach looks promising as three news releases trumpeting the possibilities indicate. First, there’s the June 17, 2020 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release,

Scientists are working overtime to find an effective treatment for COVID-19, the illness caused by the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Many of these efforts target a specific part of the virus, such as the spike protein. Now, researchers reporting in Nano Letters have taken a different approach, using nanosponges coated with human cell membranes –– the natural targets of the virus –– to soak up SARS-CoV-2 and keep it from infecting cells in a petri dish.

To gain entry, SARS-CoV-2 uses its spike protein to bind to two known proteins on human cells, called ACE2 and CD147. Blocking these interactions would keep the virus from infecting cells, so many researchers are trying to identify drugs directed against the spike protein. Anthony Griffiths, Liangfang Zhang and colleagues had a different idea: making a nanoparticle decoy with the virus’ natural targets, including ACE2 and CD147, to lure SARS-CoV-2 away from cells. And to test this idea, they conducted experiments with the actual SARS-CoV-2 virus in a biosafety level 4 lab.

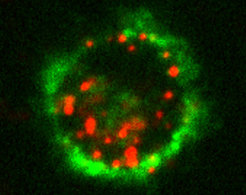

The researchers coated a nanoparticle polymer core with cell membranes from either human lung epithelial cells or macrophages –– two cell types infected by SARS-CoV-2. They showed that the nanosponges had ACE2 and CD147, as well as other cell membrane proteins, projecting outward from the polymer core. When administered to mice, the nanosponges did not show any short-term toxicity. Then, the researchers treated cells in a dish with SARS-CoV-2 and the lung epithelial or macrophage nanosponges. Both decoys neutralized SARS-CoV-2 and prevented it from infecting cells to a similar extent. The researchers plan to next test the nanosponges in animals before moving to human clinical trials. In theory, the nanosponge approach would work even if SARS-CoV-2 mutates to resist other therapies, and it could be used against other viruses, as well, the researchers say.

…

There are two research teams involved, one at Boston University and the other at the University of California at San Diego (UC San Diego or UCSD). The June 18, 2020 Boston University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Kat J. McAlpine adds more details about the research, provides some insights from the researchers, and is a little redundant if you’ve already seen the ACS news release,

Imagine if scientists could stop the coronavirus infection in its tracks simply by diverting its attention away from living lung cells? A new therapeutic countermeasure, announced in a Nano Letters study by researchers from Boston University’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) and the University of California San Diego, appears to do just that in experiments that were carried out at the NEIDL in Boston.

The breakthrough technology could have major implications for fighting the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the global pandemic that’s already claimed nearly 450,000 lives and infected more than 8 million people. But, perhaps even more significantly, it has the potential to be adapted to combat virtually any virus, such as influenza or even Ebola.

“I was skeptical at the beginning because it seemed too good to be true,” says NEIDL microbiologist Anna Honko, one of the co-first authors on the study. “But when I saw the first set of results in the lab, I was just astonished.”

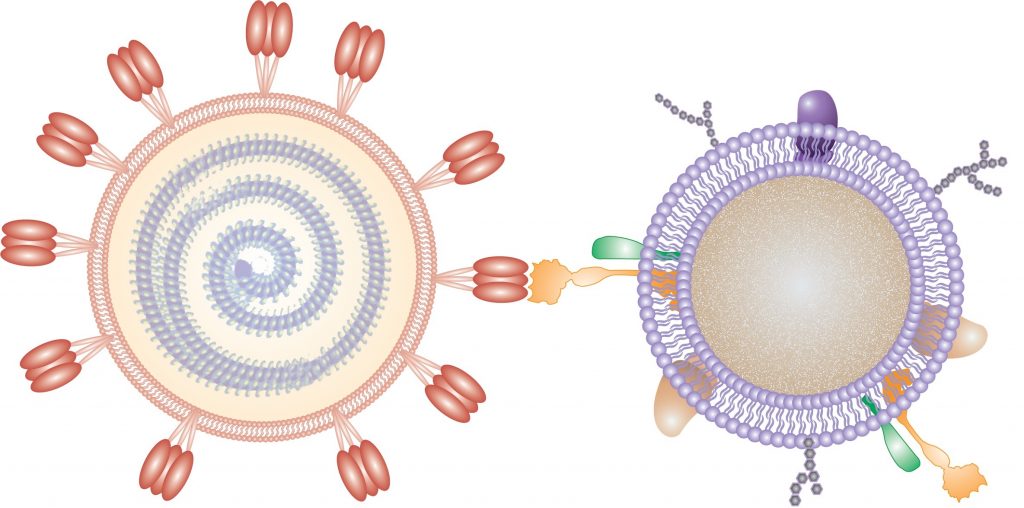

The technology consists of very small, nanosized drops of polymers–essentially, soft biofriendly plastics–covered in fragments of living lung cell and immune cell membranes.

“It looks like a nanoparticle coated in pieces of cell membrane,” Honko says. “The small polymer [droplet] mimics a cell having a membrane around it.”

The SARS-CoV-2 virus seeks out unique signatures of lung cell membranes and latches onto them. When that happens inside the human body, the coronavirus infection takes hold, with the SARS-CoV-2 viruses hijacking lung cells to replicate their own genetic material. But in experiments at the NEIDL, BU researchers observed that polymer droplets laden with pieces of lung cell membrane did a better job of attracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus than living lung cells. [emphasis mine]

By fusing with the SARS-CoV-2 virus better than living cells can, the nanotechnology appears to be an effective countermeasure to coronavirus infection, preventing SARS-CoV-2 from attacking cells.

“Our guess is that it acts like a decoy, it competes with cells for the virus,” says NEIDL microbiologist Anthony Griffiths, co-corresponding author on the study. “They are little bits of plastic, just containing the outer pieces of cells with none of the internal cellular machinery contained inside living cells. Conceptually, it’s such a simple idea. It mops up the virus like a sponge.”

That attribute is why the UC San Diego and BU research team call the technology “nanosponges.” Once SARS-CoV-2 binds with the cell fragments inside a nanosponge droplet–each one a thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair–the coronavirus dies. Although the initial results are based on experiments conducted in cell culture dishes, the researchers believe that inside a human body, the biodegradable nanosponges and the SARS-CoV-2 virus trapped inside them could then be disposed of by the body’s immune system. The immune system routinely breaks down and gets rid of dead cell fragments caused by infection or normal cell life cycles.

There is also another important effect that the nanosponges have in the context of coronavirus infection. Honko says nanosponges containing fragments of immune cells can soak up cellular signals that increase inflammation [emphases mine]. Acute respiratory distress, caused by an inflammatory cascade inside the lungs, is the most deadly aspect of the coronavirus infection, sending patients into the intensive care unit for oxygen or ventilator support to help them breathe.

But the nanosponges, which can attract the inflammatory molecules that send the immune system into dangerous overdrive, can help tamp down that response, Honko says. By using both kinds of nanosponges, some containing lung cell fragments and some containing pieces of immune cells, she says it’s possible to “attack the coronavirus and the [body’s] response” responsible for disease and eventual lung failure.

At the NEIDL, Honko and Griffiths are now planning additional experiments to see how well the nanosponges can prevent coronavirus infection in animal models of the disease. They plan to work closely with the team of engineers at UC San Diego, who first developed the nanosponges more than a decade ago, to tailor the technology for eventual safe and effective use in humans.

“Traditionally, drug developers for infectious diseases dive deep on the details of the pathogen in order to find druggable targets,” said Liangfang Zhang, a UC San Diego nanoengineer and leader of the California-based team, according to a UC San Diego press release. “Our approach is different. We only need to know what the target cells are. And then we aim to protect the targets by creating biomimetic decoys.”

When the novel coronavirus first appeared, the idea of using the nanosponges to combat the infection came to Zhang almost immediately. He reached out to the NEIDL for help. Looking ahead, the BU and UC San Diego collaborators believe the nanosponges can easily be converted into a noninvasive treatment.

“We should be able to drop it right into the nose,” Griffiths says. “In humans, it could be something like a nasal spray.”

Honko agrees: “That would be an easy and safe administration method that should target the appropriate [respiratory] tissues. And if you wanted to treat patients that are already intubated, you could deliver it straight into the lung.”

Griffiths and Honko are especially intrigued by the nanosponges as a new platform for treating all types of viral infections. “The broad spectrum aspect of this is exceptionally appealing,” Griffiths says. The researchers say the nanosponge could be easily adapted to house other types of cell membranes preferred by other viruses, creating many new opportunities to use the technology against other tough-to-treat infections like the flu and even deadly hemorrhagic fevers caused by Ebola, Marburg, or Lassa viruses.

“I’m interested in seeing how far we can push this technology,” Honko says.

The University of California at* San Diego has released a video illustrating the nanosponges work,

There’s also this June 17, 2020 University of California at San Diego (UC San Diego) news release (also on EurekAlert) by Ioana Patringenaru, which offers extensive new detail along with, if you’ve read one or both of the news releases in the above, a few redundant bits,

Nanoparticles cloaked in human lung cell membranes and human immune cell membranes can attract and neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus in cell culture, causing the virus to lose its ability to hijack host cells and reproduce.

The first data describing this new direction for fighting COVID-19 were published on June 17 in the journal Nano Letters. The “nanosponges” were developed by engineers at the University of California San Diego and tested by researchers at Boston University.

The UC San Diego researchers call their nano-scale particles “nanosponges” because they soak up harmful pathogens and toxins.

In lab experiments, both the lung cell and immune cell types of nanosponges caused the SARS-CoV-2 virus to lose nearly 90% of its “viral infectivity” in a dose-dependent manner. Viral infectivity is a measure of the ability of the virus to enter the host cell and exploit its resources to replicate and produce additional infectious viral particles.

Instead of targeting the virus itself, these nanosponges are designed to protect the healthy cells the virus invades.

“Traditionally, drug developers for infectious diseases dive deep on the details of the pathogen in order to find druggable targets. Our approach is different. We only need to know what the target cells are. And then we aim to protect the targets by creating biomimetic decoys,” said Liangfang Zhang, a nanoengineering professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

His lab first created this biomimetic nanosponge platform more than a decade ago and has been developing it for a wide range of applications ever since [emphasis mine]. When the novel coronavirus appeared, the idea of using the nanosponge platform to fight it came to Zhang “almost immediately,” he said.

In addition to the encouraging data on neutralizing the virus in cell culture, the researchers note that nanosponges cloaked with fragments of the outer membranes of macrophages could have an added benefit: soaking up inflammatory cytokine proteins, which are implicated in some of the most dangerous aspects of COVID-19 and are driven by immune response to the infection.

Making and testing COVID-19 nanosponges

Each COVID-19 nanosponge–a thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair–consists of a polymer core coated in cell membranes extracted from either lung epithelial type II cells or macrophage cells. The membranes cover the sponges with all the same protein receptors as the cells they impersonate–and this inherently includes whatever receptors SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter cells in the body.

The researchers prepared several different concentrations of nanosponges in solution to test against the novel coronavirus. To test the ability of the nanosponges to block SARS-CoV-2 infectivity, the UC San Diego researchers turned to a team at Boston University’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) to perform independent tests. In this BSL-4 lab–the highest biosafety level for a research facility–the researchers, led by Anthony Griffiths, associate professor of microbiology at Boston University School of Medicine, tested the ability of various concentrations of each nanosponge type to reduce the infectivity of live SARS-CoV-2 virus–the same strains that are being tested in other COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine research.

At a concentration of 5 milligrams per milliliter, the lung cell membrane-cloaked sponges inhibited 93% of the viral infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. The macrophage-cloaked sponges inhibited 88% of the viral infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. Viral infectivity is a measure of the ability of the virus to enter the host cell and exploit its resources to replicate and produce additional infectious viral particles.

“From the perspective of an immunologist and virologist, the nanosponge platform was immediately appealing as a potential antiviral because of its ability to work against viruses of any kind. This means that as opposed to a drug or antibody that might very specifically block SARS-CoV-2 infection or replication, these cell membrane nanosponges might function in a more holistic manner in treating a broad spectrum of viral infectious diseases. I was optimistically skeptical initially that it would work, and then thrilled once I saw the results and it sunk in what this could mean for therapeutic development as a whole,” said Anna Honko, a co-first author on the paper and a Research Associate Professor, Microbiology at Boston University’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL).

In the next few months, the UC San Diego researchers and collaborators will evaluate the nanosponges’ efficacy in animal models. The UC San Diego team has already shown short-term safety in the respiratory tracts and lungs of mice. If and when these COVID-19 nanosponges will be tested in humans depends on a variety of factors, but the researchers are moving as fast as possible.

“Another interesting aspect of our approach is that even as SARS-CoV-2 mutates, as long as the virus can still invade the cells we are mimicking, our nanosponge approach should still work. I’m not sure this can be said for some of the vaccines and therapeutics that are currently being developed,” said Zhang.

The researchers also expect these nanosponges would work against any new coronavirus or even other respiratory viruses, including whatever virus might trigger the next respiratory pandemic.

Mimicking lung epithelial cells and immune cells

Since the novel coronavirus often infects lung epithelial cells as the first step in COVID-19 infection, Zhang and his colleagues reasoned that it would make sense to cloak a nanoparticle in fragments of the outer membranes of lung epithelial cells to see if the virus could be tricked into latching on it instead of a lung cell.

Macrophages, which are white blood cells that play a major role in inflammation, also are very active in the lung during the course of a COVID-19 illness, so Zhang and colleagues created a second sponge cloaked in macrophage membrane.

The research team plans to study whether the macrophage sponges also have the ability to quiet cytokine storms in COVID-19 patients.

“We will see if the macrophage nanosponges can neutralize the excessive amount of these cytokines as well as neutralize the virus,” said Zhang.

Using macrophage cell fragments as cloaks builds on years of work to develop therapies for sepsis using macrophage nanosponges.

In a paper published in 2017 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Zhang and a team of researchers at UC San Diego showed that macrophage nanosponges can safely neutralize both endotoxins and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the bloodstream of mice. A San Diego biotechnology company co-founded by Zhang called Cellics Therapeutics is working to translate this macrophage nanosponge work into the clinic.

A potential COVID-19 therapeutic The COVID-19 nanosponge platform has significant testing ahead of it before scientists know whether it would be a safe and effective therapy against the virus in humans, Zhang cautioned [emphasis mine]. But if the sponges reach the clinical trial stage, there are multiple potential ways of delivering the therapy that include direct delivery into the lung for intubated patients, via an inhaler like for asthmatic patients, or intravenously, especially to treat the complication of cytokine storm.

A therapeutic dose of nanosponges might flood the lung with a trillion or more tiny nanosponges that could draw the virus away from healthy cells. Once the virus binds with a sponge, “it loses its viability and is not infective anymore, and will be taken up by our own immune cells and digested,” said Zhang.

“I see potential for a preventive treatment, for a therapeutic that could be given early because once the nanosponges get in the lung, they can stay in the lung for some time,” Zhang said. “If a virus comes, it could be blocked if there are nanosponges waiting for it.”

Growing momentum for nanosponges

Zhang’s lab at UC San Diego created the first membrane-cloaked nanoparticles over a decade ago. The first of these nanosponges were cloaked with fragments of red blood cell membranes. These nanosponges are being developed to treat bacterial pneumonia and have undergone all stages of pre-clinical testing by Cellics Therapeutics, the San Diego startup cofounded by Zhang. The company is currently in the process of submitting the investigational new drug (IND) application to the FDA for their lead candidate: red blood cell nanosponges for the treatment of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia. The company estimates the first patients in a clinical trial will be dosed next year.

The UC San Diego researchers have also shown that nanosponges can deliver drugs to a wound site; sop up bacterial toxins that trigger sepsis; and intercept HIV before it can infect human T cells.

The basic construction for each of these nanosponges is the same: a biodegradable, FDA-approved polymer core is coated in a specific type of cell membrane, so that it might be disguised as a red blood cell, or an immune T cell or a platelet cell. The cloaking keeps the immune system from spotting and attacking the particles as dangerous invaders.

“I think of the cell membrane fragments as the active ingredients. This is a different way of looking at drug development,” said Zhang. “For COVID-19, I hope other teams come up with safe and effective therapies and vaccines as soon as possible. At the same time, we are working and planning as if the world is counting on us.”

I wish the researchers good luck. For the curious, here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Cellular Nanosponges Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity by Qiangzhe Zhang, Anna Honko, Jiarong Zhou, Hua Gong, Sierra N. Downs, Jhonatan Henao Vasquez, Ronnie H. Fang, Weiwei Gao, Anthony Griffiths, and Liangfang Zhang. Nano Lett. 2020, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02278 Publication Date:June 17, 2020 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper appears to be open access.

Here, too, is the Cellics Therapeutics website.

*University of California as San Diego corrected to University of California at San Diego on Dec. 30, 2020.