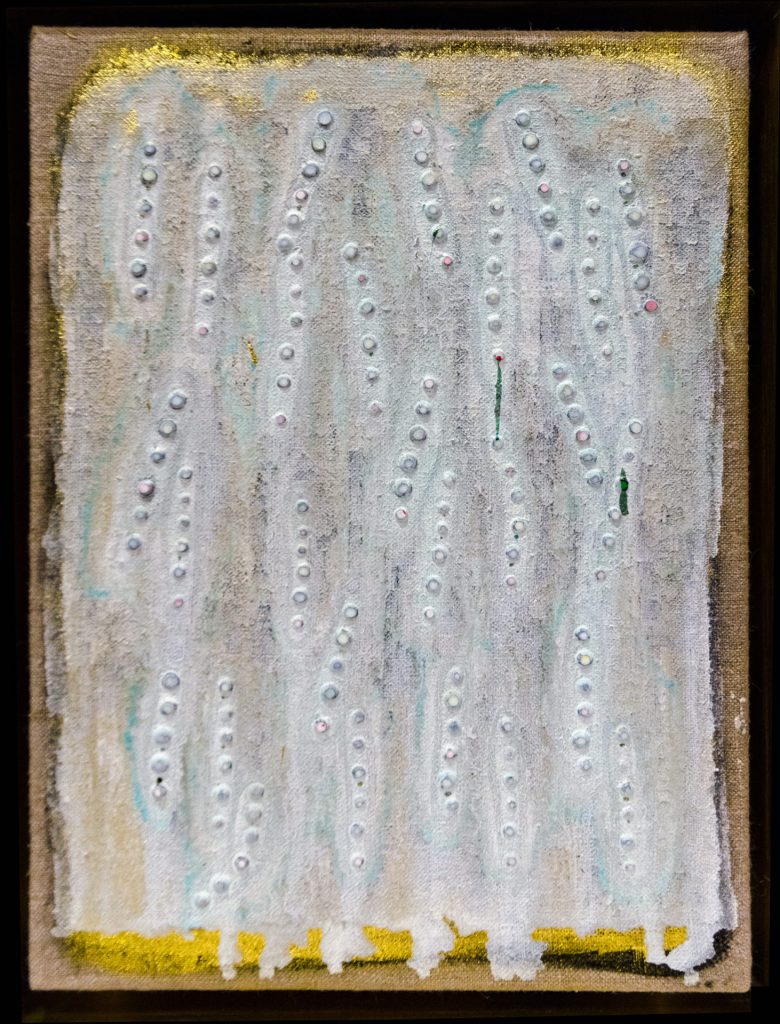

The artist credited with the work seen in the above, Joseph Cohen, has done something remarkable with carbon nanotubes (CNTs). Something even more remarkable than the painting as Sarah Cascone recounts in her August 30, 2019 article for artnet.com (Note: A link has been removed),

Not every artist can say that his or her work is helping in the fight against cancer. But over the past several years, Joseph Cohen has done just that, working to develop a new, high-tech paint that can be used not only on canvas, but also to detect cancers and medical conditions such as hypertension and diabetes.

Sloan Kettering Institute scientist Daniel Heller first suggested that Cohen come work at his lab after seeing the artist’s work, which is often made with pigments that incorporate diamond dust and gold, at the DeBuck Gallery in New York.

“We initially thought that in working with an artist, we would make art to shed a little light on our science for the public,” Heller told the Memorial Sloan Kettering blog. “But the collaboration actually taught us something that could help us shine a light on cancer.”

For Cohen, the project was initially intended to develop a new way of art-making. In Heller’s lab, he worked with carbon nanotubes, which Heller was already employing in cancer research, for their optical properties. “They fluoresce in the infrared spectrum,” Cohen says. “That gives artists the opportunity to create paintings in a new spectrum, with a whole new palette of colors.”

Because human eyesight is limited, we can’t actually see infrared fluorescence. But using a special short-wave infrared camera, Cohen is able to document otherwise invisible effects, revealing the carbon nanotube paint’s hidden colors.

“What you’re perceiving as a static painting is actually in motion,” Cohen says. “I’m creating paintings that exist outside of the visible experience.”

Art Supplies—and a Diagnostic Tool

That same imaging technique can be used by doctors looking for microalbuminuria, a condition that causes the kidneys to leak trace amounts of albumin into urine, which is an early sign of of several cancers, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Cohen helped co-author a paper published this month in Nature Communications about using the nanosensor paint in litmus paper tests with patient urine samples. The study found that the paint, when viewed through infrared light, was able to reveal the presence of albumin based on changes in the paint’s fluorescence after being exposed to the urine sample.“It’s easy to detect albumen with a dipstick if there’s a lot of levels in the urine, but that would be like looking at stage four cancer,” Cohen says. “This is early detection.”

What’s more, a nanosensor paint can be easily used around the world, even in poor areas that don’t have access to the best diagnostic technologies. Doctors may even be able to view the urine samples using an infrared imaging attachments on their smartphones.

…

Amazing, eh? If you have the time, do read Cascone’s article in its entirety and should your curiosity be insatiable, there’s also an August 22, 2019 posting by Jim Stallard on the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center blog,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Synthetic molecular recognition nanosensor paint for microalbuminuria by Januka Budhathoki-Uprety, Janki Shah, Joshua A. Korsen, Alysandria E. Wayne, Thomas V. Galassi, Joseph R. Cohen, Jackson D. Harvey, Prakrit V. Jena, Lakshmi V. Ramanathan, Edgar A. Jaimes & Daniel A. Heller. Nature Communicationsvolume 10, Article number: 3605 (2019) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11583-1 Published: 09 August 2019

This paper is open access.

Joseph Cohen has graced this blog before in a May 3, 2019 posting titled, Where do I stand? a graphene artwork. It seems Cohen is very invested in using nanoscale carbon particles for his art.