It’s always interesting to come across different news releases announcing the same research. In this case I have two news releases, one from the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and one from the University of Arizona. Let’s start with the July 19, 2022 news item on phys.org (originated by the US NSF),

Astronomers at the University of Arizona have developed a theory to explain the presence of the largest molecules known to exist in interstellar gas.

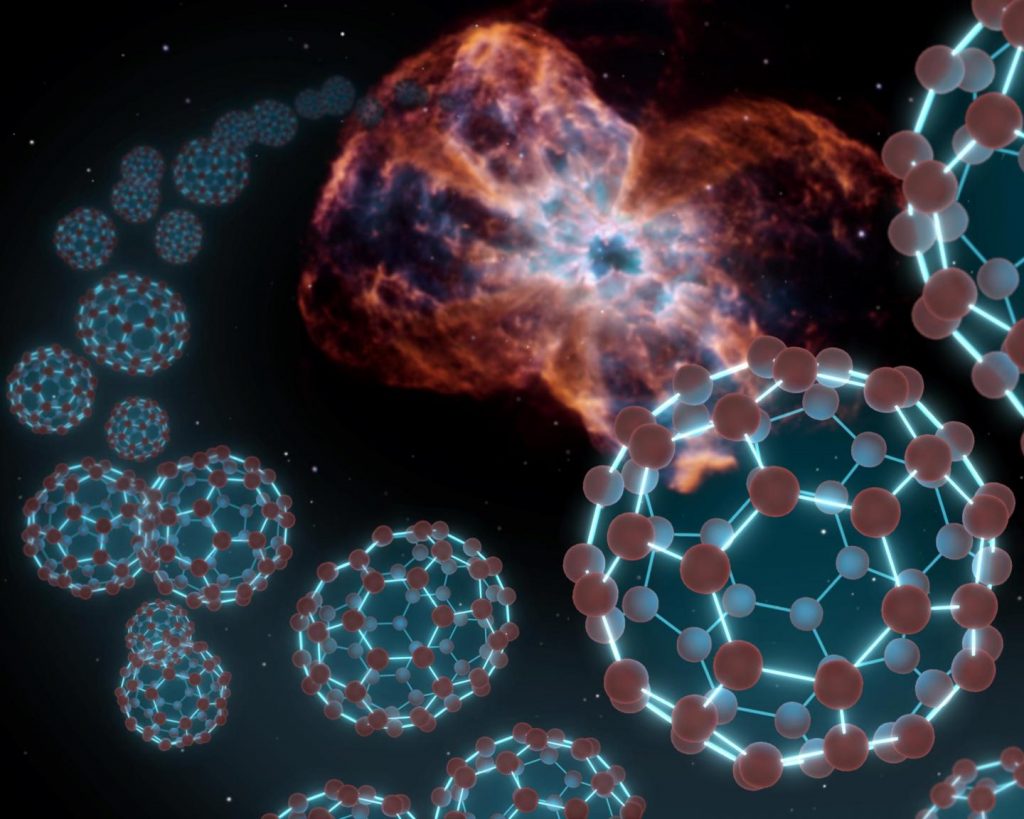

The team simulated the environment of dying stars and observed the formation of buckyballs (carbon atoms linked to three other carbon atoms by covalent bonds) and carbon nanotubes (rolled up sheets of single-layer carbon atoms). The findings indicate that buckyballs and carbon nanotubes can form when silicon carbide dust — known to be proximate to dying stars — releases carbon in reaction to intense heat, shockwaves and high energy particles.

…

Here’s the rest of the July 18, 2022 NSF news release, Note: A link has been removed,

“We know from infrared observations that buckyballs populate the interstellar medium,” said Jacob Bernal, who led the research. “The big problem has been explaining how these massive, complex carbon molecules could possibly form in an environment saturated with hydrogen, which is what you typically have around a dying star.”

Rearranging the structure of graphene (a sheet of single-layer carbon atoms) could create buckyballs and nanotubes. Building on that, the team heated silicon carbide samples to temperatures that would mimic the aura of a dying star and observed the formation of nanotubes.

“We were surprised we could make these extraordinary structures,” Bernal said. “Chemically, our nanotubes are very simple, but they are extremely beautiful.”

Buckyballs are the largest molecules currently known to occur in interstellar space. It is now known that buckyballs containing 60 to 70 carbon atoms are common.

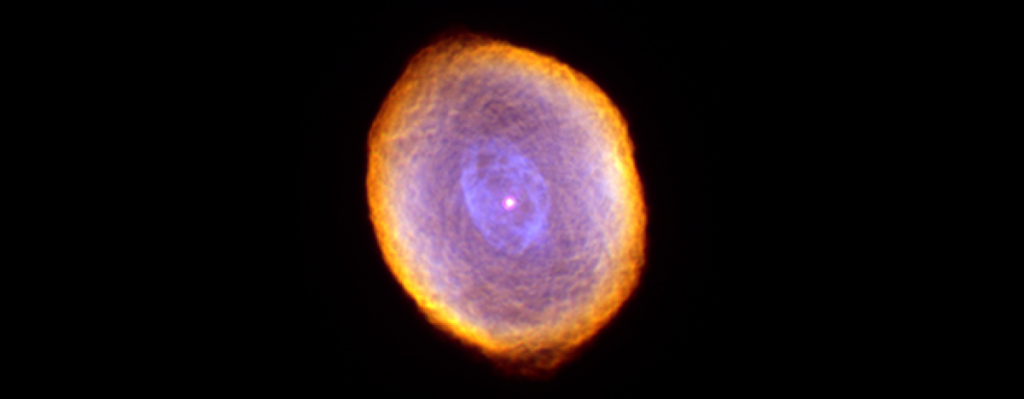

“We know the raw material is there, and we know the conditions are very close to what you’d see near the envelope of a dying star,” study co-author Lucy Ziurys said. “Shock waves pass through the envelope, and the temperature and pressure conditions have been shown to exist in space. We also see buckyballs in planetary nebulae — in other words, we see the beginning and the end products you would expect in our experiments.”

A June 16, 2022 University of Arizona news release by Daniel Stolte (also on EurekAlert) takes a context-rich approach to writing up the proposed theory for how buckyballs and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) form (Note: Links have been removed),

In the mid-1980s, the discovery of complex carbon molecules drifting through the interstellar medium garnered significant attention, with possibly the most famous examples being Buckminsterfullerene, or “buckyballs” – spheres consisting of 60 or 70 carbon atoms. However, scientists have struggled to understand how these molecules can form in space.

In a paper accepted for publication in the Journal of Physical Chemistry A, researchers from the University of Arizona suggest a surprisingly simple explanation. After exposing silicon carbide – a common ingredient of dust grains in planetary nebulae – to conditions similar to those found around dying stars, the researchers observed the spontaneous formation of carbon nanotubes, which are highly structured rod-like molecules consisting of multiple layers of carbon sheets. The findings were presented on June 16 [2022] at the 240th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Pasadena, California.

Led by UArizona researcher Jacob Bernal, the work builds on research published in 2019, when the group showed that they could create buckyballs using the same experimental setup. The work suggests that buckyballs and carbon nanotubes could form when the silicon carbide dust made by dying stars is hit by high temperatures, shock waves and high-energy particles, leaching silicon from the surface and leaving carbon behind.

The findings support the idea that dying stars may seed the interstellar medium with nanotubes and possibly other complex carbon molecules. The results have implications for astrobiology, as they provide a mechanism for concentrating carbon that could then be transported to planetary systems.

“We know from infrared observations that buckyballs populate the interstellar medium,” said Bernal, a postdoctoral research associate in the UArizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “The big problem has been explaining how these massive, complex carbon molecules could possibly form in an environment saturated with hydrogen, which is what you typically have around a dying star.”

The formation of carbon-rich molecules, let alone species containing purely carbon, in the presence of hydrogen is virtually impossible due to thermodynamic laws. The new study findings offer an alternative scenario: Instead of assembling individual carbon atoms, buckyballs and nanotubes could result from simply rearranging the structure of graphene – single-layered carbon sheets that are known to form on the surface of heated silicon carbide grains.

This is exactly what Bernal and his co-authors observed when they heated commercially available silicon carbide samples to temperatures occurring in dying or dead stars and imaged them. As the temperature approached 1,050 degreesCelsius, small hemispherical structures with the approximate size of about 1 nanometer were observed at the grain surface. Within minutes of continued heating, the spherical buds began to grow into rod-like structures, containing several graphene layers with curvature and dimensions indicating a tubular form. The resulting nanotubules ranged from about 3 to 4 nanometers in length and width, larger than buckyballs. The largest imaged specimens were comprised of more than four layers of graphitic carbon. During the heating experiment, the tubes were observed to wiggle before budding off the surface and getting sucked into the vacuum surrounding the sample.

“We were surprised we could make these extraordinary structures,” Bernal said. “Chemically, our nanotubes are very simple, but they are extremely beautiful.”

Named after their resemblance to architectural works by Richard Buckminster Fuller, fullerenes are the largest molecules currently known to occur in interstellar space, which for decades was believed to be devoid of any molecules containing more than a few atoms, 10 at most. It is now well established that the fullerenes C60 and C70, which contain 60 or 70 carbon atoms, respectively, are common ingredients of the interstellar medium.

One of the first of its kind in the world, the transmission electron microscope housed at the Kuiper Materials Imaging and Characterization Facility at UArizona is uniquely suited to simulate the planetary nebula environment. Its 200,000-volt electron beam can probe matter down to 78 picometers – the distance of two hydrogen atoms in a water molecule – making it possible to see individual atoms. The instrument operates in a vacuum closely resembling the pressure – or lack thereof – thought to exist in circumstellar environments.

While a spherical C60 molecule measures 0.7 nanometers in diameter, the nanotube structures formed in this experiment measured several times the size of C60, easily exceeding 1,000 carbon atoms. The study authors are confident their experiments accurately replicated the temperature and density conditions that would be expected in a planetary nebula, said co-author Lucy Ziurys, a UArizona Regents Professor of Astronomy, Chemistry and Biochemistry.

“We know the raw material is there, and we know the conditions are very close to what you’d see near the envelope of a dying star,” she said. “There are shock waves that pass through the envelope, so the temperature and pressure conditions have been shown to exist in space. We also see buckyballs in these planetary nebulae – in other words, we see the beginning and the end products you would expect in our experiments.”

These experimental simulations suggest that carbon nanotubes, along with the smaller fullerenes, are subsequently injected into the interstellar medium. Carbon nanotubes are known to have high stability against radiation, and fullerenes are able to survive for millions of years when adequately shielded from high-energy cosmic radiation. Carbon-rich meteorites, such as carbonaceous chondrites, could contain these structures as well, the researchers propose.

According to study co-author Tom Zega, a professor in the UArizona Lunar and Planetary Lab, the challenge is finding nanotubes in these meteorites, because of the very small grain sizes and because the meteorites are a complex mix of organic and inorganic materials, some with sizes similar to those of nanotubes.

“Nonetheless, our experiments suggest that such materials could have formed in interstellar space,” Zega said. “If they survived the journey to our local part of the galaxy where our solar system formed some 4.5 billion years ago, then they could be preserved inside of the material that was left over.”

Zega said a prime example of such leftover material is Bennu, a carbonaceous near-Earth asteroid from which NASA’s UArizona-led OSIRIS-REx mission scooped up a sample in October 2020. Scientists are eagerly awaiting the arrival of that sample, scheduled for 2023.

“Asteroid Bennu could have preserved these materials, so it is possible we may find nanotubes in them,” Zega said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Destructive Processing of Silicon Carbide Grains: Experimental Insights into the Formation of Interstellar Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes by Jacob J. Bernal, Thomas J. Zega, and Lucy M. Ziurys. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c01441 Publication Date:June 27, 2022 © 2022 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.