Researchers in India have found a way to make use of fish ‘biowaste’ according to a Sept. 6, 2016 news item on Nanowerk,

Large quantities of fish are consumed in India on a daily basis, which generates a huge amount of fish “biowaste” materials. In an attempt to do something positive with this biowaste, a team of researchers at Jadavpur University in Koltata, India explored recycling the fish byproducts into an energy harvester for self-powered electronics.

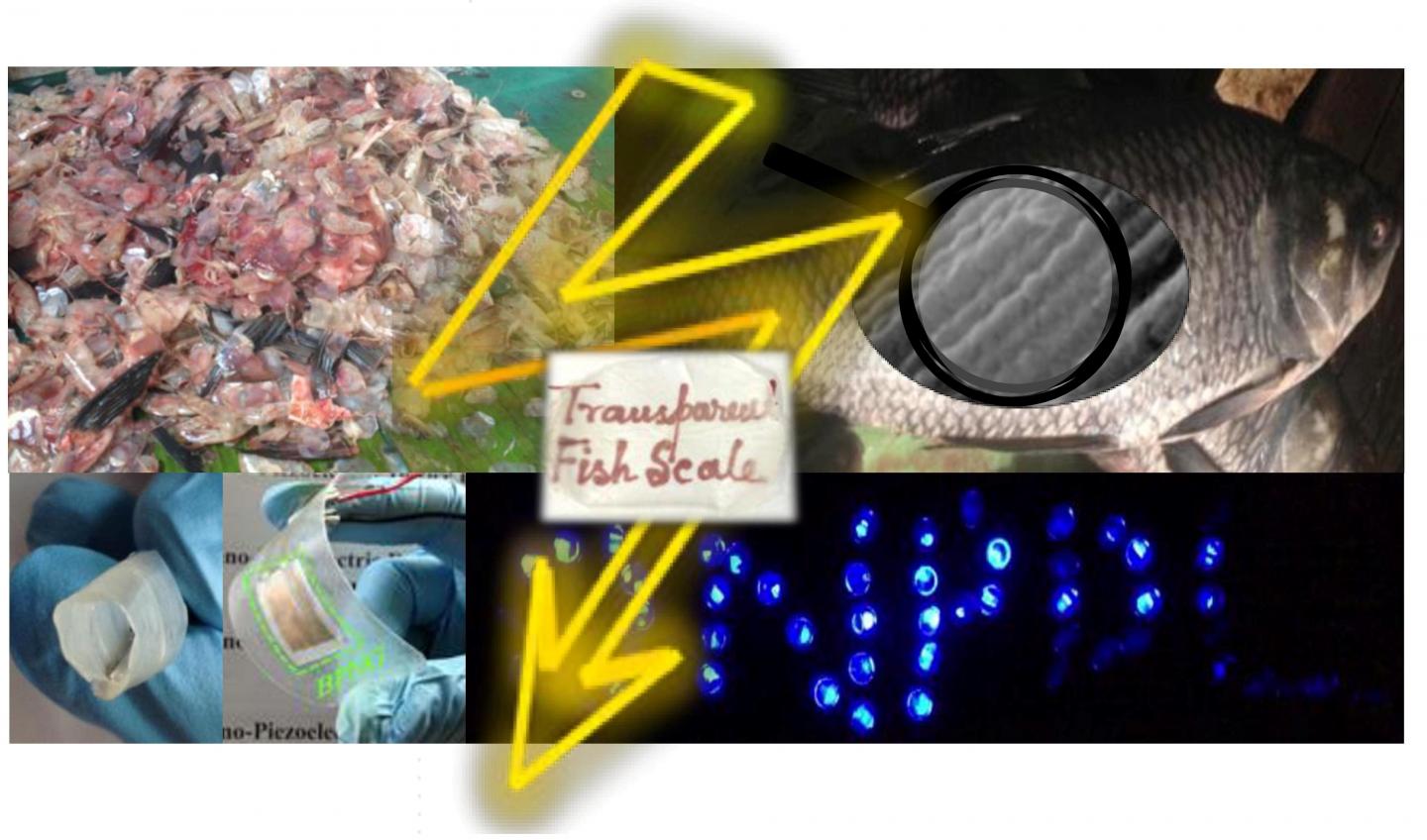

Caption: Waste fish scales (upper left corner) are used to fabricate flexible nanogenerator (lower left) that power up more than 50 blue LEDs (lower right). An enlarged microscopic view of a fish scale shows the well-aligned collagen fibrils (upper right). The possibility of making a fish scale transparent (middle) and rollable (extreme left lower corner) is also illustrated. Credit: Sujoy Kuman Ghosh and Dipankar Mandal/Jadavpur University

A Sept. 6, 2016 American Institute of Physics news release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, describes the research in more detail,

The basic premise behind the researchers’ work is simple: Fish scales contain collagen fibers that possess a piezoelectric property, which means that an electric charge is generated in response to applying a mechanical stress. As the team reports this week in Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing, they were able to harness this property to fabricate a bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator.

To do this, the researchers first “collected biowaste in the form of hard, raw fish scales from a fish processing market, and then used a demineralization process to make them transparent and flexible,” explained Dipankar Mandal, assistant professor, Organic Nano-Piezoelectric Device Laboratory, Department of Physics, at Jadavpur University.

The collagens within the processed fish scales serve as an active piezoelectric element.

“We were able to make a bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator — a.k.a. energy harvester — with electrodes on both sides, and then laminated it,” Mandal said.

While it’s well known that a single collagen nanofiber exhibits piezoelectricity, until now no one had attempted to focus on hierarchically organizing the collagen nanofibrils within the natural fish scales.

“We wanted to explore what happens to the piezoelectric yield when a bunch of collagen nanofibrils are hierarchically well aligned and self-assembled in the fish scales,” he added. “And we discovered that the piezoelectricity of the fish scale collagen is quite large (~5 pC/N), which we were able to confirm via direct measurement.”

Beyond that, the polarization-electric field hysteresis loop and resulting strain-electric field hysteresis loop — proof of a converse piezoelectric effect — caused by the “nonlinear” electrostriction effect backed up their findings.

The team’s work is the first known demonstration of the direct piezoelectric effect of fish scales from electricity generated by a bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator under mechanical stimuli — without the need for any post-electrical poling treatments.

“We’re well aware of the disadvantages of the post-processing treatments of piezoelectric materials,” Mandal noted.

To explore the fish scale collagen’s self-alignment phenomena, the researchers used near-edge X-ray absorption fine-structure spectroscopy, measured at the Raja Ramanna Centre for Advanced Technology in Indore, India.

Experimental and theoretical tests helped them clarify the energy scavenging performance of the bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator. It’s capable of scavenging several types of ambient mechanical energies — including body movements, machine and sound vibrations, and wind flow. Even repeatedly touching the bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator with a finger can turn on more than 50 blue LEDs.

“We expect our work to greatly impact the field of self-powered flexible electronics,” Mandal said. “To date, despite several extraordinary efforts, no one else has been able to make a biodegradable energy harvester in a cost-effective, single-step process.”

The group’s work could potentially be for use in transparent electronics, biocompatible and biodegradable electronics, edible electronics, self-powered implantable medical devices, surgeries, e-healthcare monitoring, as well as in vitro and in vivo diagnostics, apart from its myriad uses for portable electronics.

“In the future, our goal is to implant a bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator into a heart for pacemaker devices, where it will continuously generate power from heartbeats for the device’s operation,” Mandal said. “Then it will degrade when no longer needed. Since heart tissue is also composed of collagen, our bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator is expected to be very compatible with the heart.”

The group’s bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator may also help with targeted drug delivery, which is currently generating interest as a way of recovering in vivo cancer cells and also to stimulate different types of damaged tissues.

“So we expect our work to have enormous importance for next-generation implantable medical devices,” he added.

“Our end goal is to design and engineer sophisticated ingestible electronics composed of nontoxic materials that are useful for a wide range of diagnostic and therapeutic applications,” said Mandal.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

High-performance bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator made with fish scale by Sujoy Kumar Ghosh and Dipankar Mandal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 103701 (2016); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4961623

This paper appears to be open access.