Researchers at Rice University (Texas) have devised a new technique for carbon capture according to a June 3, 2014 news item on Nanowerk,

Rice University scientists have created an Earth-friendly way to separate carbon dioxide from natural gas at wellheads.

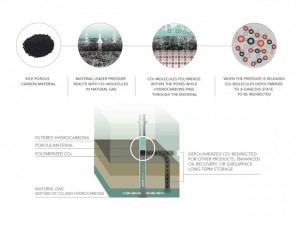

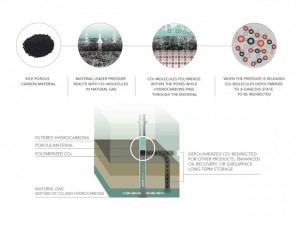

A porous material invented by the Rice lab of chemist James Tour sequesters carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, at ambient temperature with pressure provided by the wellhead and lets it go once the pressure is released. The material shows promise to replace more costly and energy-intensive processes.

A June 3, 2014 Rice University news release, which originated the news item, provides a general description of how carbon dioxide is currently removed during fossil fuel production and adds a few more details about the new technology,

Natural gas is the cleanest fossil fuel. Development of cost-effective means to separate carbon dioxide during the production process will improve this advantage over other fossil fuels and enable the economic production of gas resources with higher carbon dioxide content that would be too costly to recover using current carbon capture technologies, Tour said. Traditionally, carbon dioxide has been removed from natural gas to meet pipelines’ specifications.

The Tour lab, with assistance from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), produced the patented material that pulls only carbon dioxide molecules from flowing natural gas and polymerizes them while under pressure naturally provided by the well.

When the pressure is released, the carbon dioxide spontaneously depolymerizes and frees the sorbent material to collect more.

All of this works in ambient temperatures, unlike current high-temperature capture technologies that use up a significant portion of the energy being produced.

The news release mentions current political/legislative actions in the US and the implications for the oil and gas industry while further describing the advantages of this new technique,

“If the oil and gas industry does not respond to concerns about carbon dioxide and other emissions, it could well face new regulations,” Tour said, noting the White House issued its latest National Climate Assessment last month [May 2014] and, this week [June 2, 2014], set new rules to cut carbon pollution from the nation’s power plants.

“Our technique allows one to specifically remove carbon dioxide at the source. It doesn’t have to be transported to a collection station to do the separation,” he said. “This will be especially effective offshore, where the footprint of traditional methods that involve scrubbing towers or membranes are too cumbersome.

“This will enable companies to pump carbon dioxide directly back downhole, where it’s been for millions of years, or use it for enhanced oil recovery to further the release of oil and natural gas. Or they can package and sell it for other industrial applications,” he said.

This is an epic (Note to writer: well done) news release as only now is there a technical explanation,

The Rice material, a nanoporous solid of carbon with nitrogen or sulfur, is inexpensive and simple to produce compared with the liquid amine-based scrubbers used now, Tour said. “Amines are corrosive and hard on equipment,” he said. “They do capture carbon dioxide, but they need to be heated to about 140 degrees Celsius to release it for permanent storage. That’s a terrible waste of energy.”

Rice graduate student Chih-Chau Hwang, lead author of the paper, first tried to combine amines with porous carbon. “But I still needed to heat it to break the covalent bonds between the amine and carbon dioxide molecules,” he said. Hwang also considered metal oxide frameworks that trap carbon dioxide molecules, but they had the unfortunate side effect of capturing the desired methane as well and they are far too expensive to make for this application.

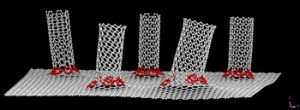

The porous carbon powder he settled on has massive surface area and turns the neat trick of converting gaseous carbon dioxide into solid polymer chains that nestle in the pores.

“Nobody’s ever seen a mechanism like this,” Tour said. “You’ve got to have that nucleophile (the sulfur or nitrogen atoms) to start the polymerization reaction. This would never work on simple activated carbon; the key is that the polymer forms and provides continuous selectivity for carbon dioxide.”

Methane, ethane and propane molecules that make up natural gas may try to stick to the carbon, but the growing polymer chains simply push them off, he said.

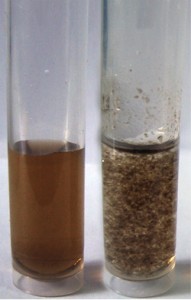

The researchers treated their carbon source with potassium hydroxide at 600 degrees Celsius to produce the powders with either sulfur or nitrogen atoms evenly distributed through the resulting porous material. The sulfur-infused powder performed best, absorbing 82 percent of its weight in carbon dioxide. The nitrogen-infused powder was nearly as good and improved with further processing.

Tour said the material did not degrade over many cycles, “and my guess is we won’t see any. After heating it to 600 degrees C for the one-step synthesis from inexpensive industrial polymers, the final carbon material has a surface area of 2,500 square meters per gram, and it is enormously robust and extremely stable.”

Apache Corp., a Houston-based oil and gas exploration and production company, funded the research at Rice and licensed the technology. Tour expected it will take time and more work on manufacturing and engineering aspects to commercialize.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Capturing carbon dioxide as a polymer from natural gas by Chih-Chau Hwang, Josiah J. Tour, Carter Kittrell, Laura Espinal, Lawrence B. Alemany, & James M. Tour. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3961 doi:10.1038/ncomms4961 Published 03 June 2014

This paper is behind a paywall.

The researchers have made an illustration of the material available,

Illustration by Tanyia Johnson/Rice University

This morning, Azonano posted a June 6, 2014 news item about a patent for carbon capture,

CO2 Solutions Inc. ( the “Corporation”), an innovator in the field of enzyme-enabled carbon capture technology, today announced it has received a Notice of Allowance from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for its patent application No. 13/264,294 entitled Process for CO2 Capture Using Micro-Particles Comprising Biocatalysts.

One might almost think these announcements were timed to coincide with the US White House’s moves.

As for CO2 Solutions, this company is located in Québec, Canada. You can find out more about the company here (you may want to click on the English language button).