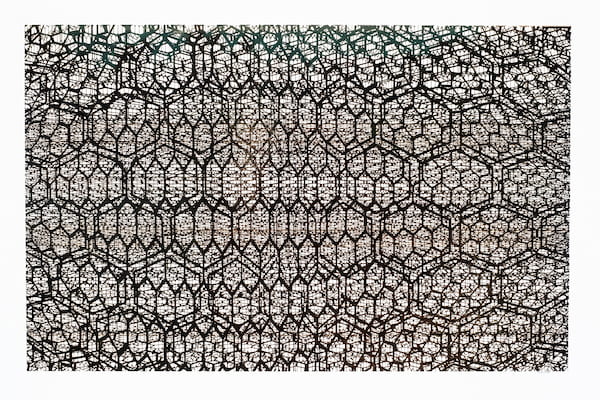

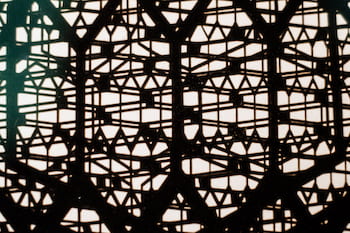

Asphaltene (or asphaltenes are) is waste material that can be turned into graphene according to scientists at Rice University (Texas, US), from a November 18, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily,

Asphaltenes, a byproduct of crude oil production, are a waste material with potential. Rice University scientists are determined to find it by converting the carbon-rich resource into useful graphene.

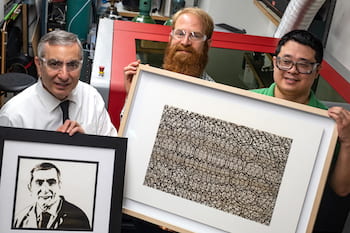

Muhammad Rahman, an assistant research professor of materials science and nanoengineering, is employing Rice’s unique flash Joule heating process to convert asphaltenes instantly into turbostratic (loosely aligned) graphene and mix it into composites for thermal, anti-corrosion and 3D-printing applications.

The process makes good use of material otherwise burned for reuse as fuel or discarded into tailing ponds and landfills. Using at least some of the world’s reserve of more than 1 trillion barrels of asphaltene as a feedstock for graphene would be good for the environment as well.

…

A November 17, 2022 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on this exciting news, Note: Links have been removed,

“Asphaltene is a big headache for the oil industry, and I think there will be a lot of interest in this,” said Rahman, who characterized the process as both a scalable and sustainable way to reduce carbon emissions from burning asphaltene.

Rahman is a lead corresponding author of the paper in Science Advances co-led by Rice chemist James Tour, whose lab developed flash Joule heating, materials scientist Pulickel Ajayan and Md Golam Kibria, an assistant professor of chemical and petroleum engineering at the University of Calgary, Canada.

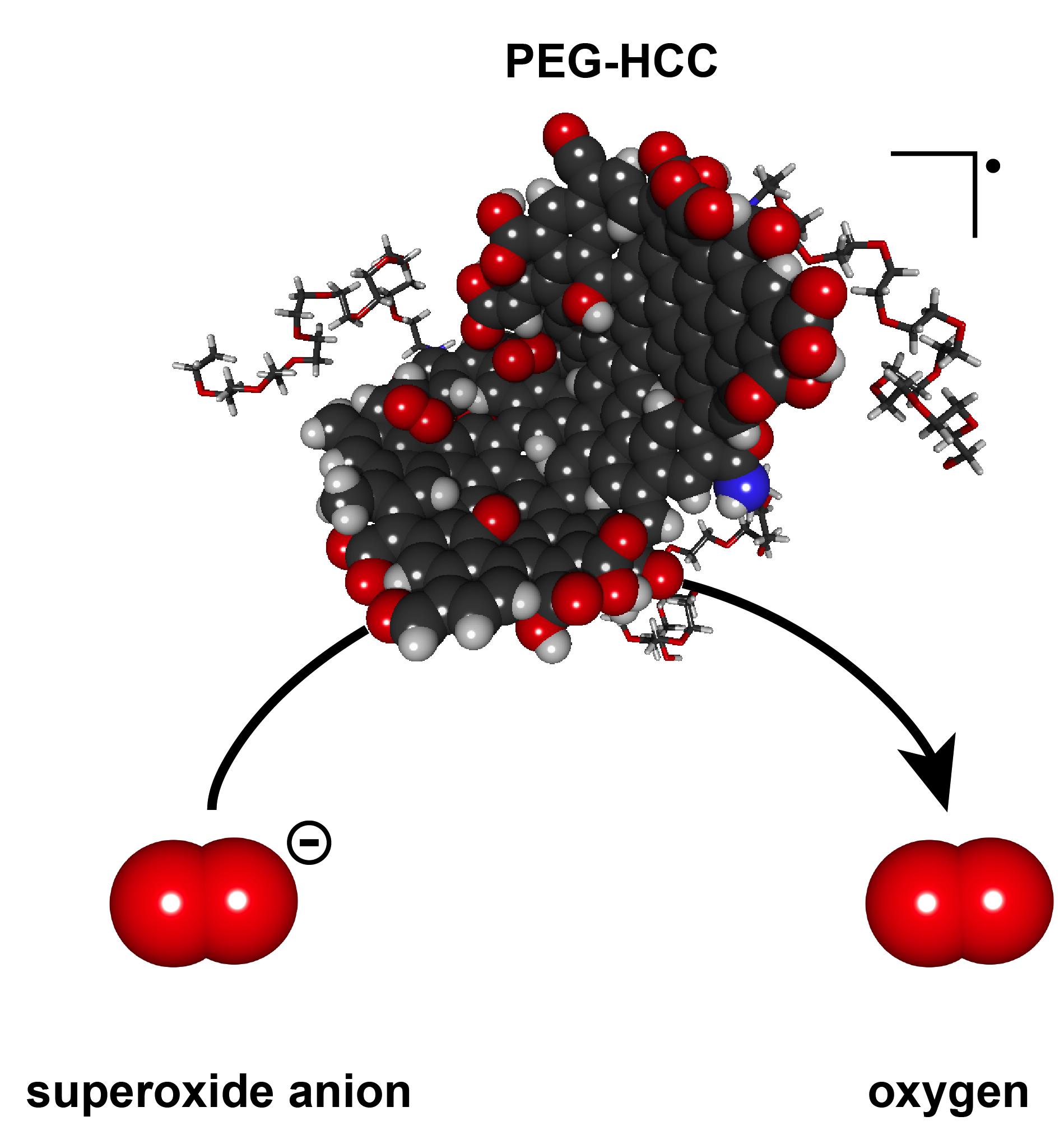

Asphaltenes are 70% to 80% carbon already. The Rice lab combines it with about 20% of carbon black to add conductivity and flashes it with a jolt of electricity, turning it into graphene in less than a second. Other elements in the feedstock, including hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur, are vented away as gases.

“We try to keep the carbon black content as low as possible because we want to maximize the utilization of asphaltene,” Rahman said.

“The government has been putting pressure on the petroleum industries to take care of this,” said Rice graduate student and co-lead author M.A.S.R. Saadi. “There are billions of barrels of asphaltene available, so we began working on this project primarily to see if we could make carbon fiber. That led us to think maybe we should try making graphene with flash Joule heating.”

Assured that Tour’s process worked as well on asphaltene as it did on various other feedstocks, including plastic, electronic waste, tires, coal fly ash and even car parts, the researchers set about making things with their graphene.

Saadi, who works with Rahman and Ajayan, mixed the graphene into composites, and then into polymer inks bound for 3D printers. “We’ve optimized the ink rheology to show that it is printable,” he said, noting the inks have no more than 10% of graphene mixed in. Mechanical testing of printed objects is forthcoming, he said.

Rice graduate student Paul Advincula, a member of the Tour lab, is co-lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice graduate students Md Shajedul Hoque Thakur, Ali Khater, Jacob Beckham and Minghe Lou, undergraduate Aasha Zinke and postdoctoral researcher Soumyabrata Roy; research fellow Shabab Saad, alumnus Ali Shayesteh Zeraati, graduate student Shariful Kibria Nabil and postdoctoral associate Md Abdullah Al Bari of the University of Calgary; graduate student Sravani Bheemasetti and Venkataramana Gadhamshetty, an associate professor, at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology and its 2D Materials of Biofilm Engineering Science and Technology Center; and research assistant Yiwen Zheng and Aniruddh Vashisth, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, of the University of Washington.

The research was funded by the Alberta Innovates for Carbon Fiber Grand Challenge programs, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-19-1-0296), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (W912HZ-21-2-0050) and the National Science Foundation (1849206, 1920954).

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Sustainable valorization of asphaltenes via flash joule heating by M.A.S.R. Saadi, Paul A. Advincula, Md Shajedul Hoque Thakur, Ali Zein Khater, Shabab Saad, Ali Shayesteh Zeraati, Shariful Kibria Nabil, Aasha Zinke, Soumyabrata Roy, Minghe Lou, Sravani N. Bheemasetti, Md Abdullah Al Bari, Yiwen Zheng, Jacob L. Beckham, Venkataramana Gadhamshetty, Aniruddh Vashisth, Md Golam Kibria, James M. Tour, Pulickel M. Ajayan, and Muhammad M. Rahman. Science Advances 18 Nov 2022 Vol 8, Issue 46 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add3555

This paper is open access.