There’s a lot of information being pumped out about COVID-19 and not all of it is as helpful as it might be. In fact, the sheer volume can seem overwhelming despite one’s best efforts to be calm.

Here are a few things I’ve used to help relieve some fo the pressure as numbers in Canada keep rising.

Inspiration from the Italians

I was thrilled to find Emily Rumball’s March 18 ,2020 article titled, “Italians making the most of quarantine is just what the world needs right now (VIDEOS),” on the Daily Hive website. The couple dancing on the balcony while Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire are shown dancing on the wall above is my favourite.

As the Italians practice social distancing and exercise caution, they are also demonstrating that “life goes on” even while struggling as one of the countries hit hardest by COVID-19.

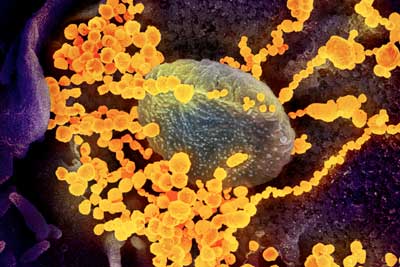

Investigating viruses and the 1918/19 pandemic vs. COVID-19

There has been some mention of and comparison to the 1918/19 pandemic (also known as the Spanish flu) in articles by people who don’t seem to be particularly well informed about that earlier pandemic. Susan Baxter offers a concise and scathing explanation for why the 1918/19 situation deteriorated as much as it did in her February 8, 2010 posting. As for this latest pandemic (COVID-19), she explains what a virus actually is and suggests we all calm down in her March 17, 2020 posting. BTW, she has an interdisciplinary PhD for work largely focused on health economics. She is also a lecturer in the health sciences programme at Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, Canada). Full disclosure: She and I have a longstanding friendship.

Marilyn J. Roossinck, a professor of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology at Pennsylvania State University, wrote a February 20, 2020 essay for The Conversation titled, “What are viruses anyway, and why do they make us so sick? 5 questions answered,”

4. SARS was a formidable foe, and then seemed to disappear. Why?

Measures to contain SARS started early, and they were very successful. The key is to stop the chain of transmission by isolating infected individuals. SARS had a short incubation period; people generally showed symptoms in two to seven days. There were no documented cases of anyone being a source of SARS without showing symptoms.

Stopping the chain of transmission is much more difficult when the incubation time is much longer, or when some people don’t get symptoms at all. This may be the case with the virus causing CoVID-19, so stopping it may take more time.

…

1918/19 pandemic vs. COVID-19

Angela Betsaida B. Laguipo, with a Bachelor of Nursing degree from the University of Baguio, Philippine is currently completing her Master’s Degree, has written a March 9, 2020 article for News Medical comparing the two pandemics,

The COVID-19 is fast spreading because traveling is an everyday necessity today, with flights from one country to another accessible to most.

Some places did manage to keep the virus at bay in 1918 with traditional and effective methods, such as closing schools, banning public gatherings, and locking down villages, which has been performed in Wuhan City, in Hubei province, China, where the coronavirus outbreak started. The same method is now being implemented in Northern Italy, where COVID-19 had killed more than 400 people.

…

The 1918 Spanish flu has a higher mortality rate of an estimated 10 to 20 percent, compared to 2 to 3 percent in COVID-19. The global mortality rate of the Spanish flu is unknown since many cases were not reported back then. About 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population contracted the disease, while the number of deaths was estimated to be up to 50 million.

…

During that time, public funds are mostly diverted to military efforts, and a public health system was still a budding priority in most countries. In most places, only the middle class or the wealthy could afford to visit a doctor. Hence, the virus has [sic] killed many people in poor urban areas where there are poor nutrition and sanitation. Many people during that time had underlying health conditions, and they can’t afford to receive health services.

…

I recommend reading Laguipo’s article in its entirety right down to the sources she cites at the end of her article.

Ed Yong’s March 20, 2020 article for The Atlantic, “Why the Coronavirus Has Been So Successful; We’ve known about SARS-CoV-2 for only three months, but scientists can make some educated guesses about where it came from and why it’s behaving in such an extreme way,” provides more information about what is currently know about the coronavirus, SATS-CoV-2,

One of the few mercies during this crisis is that, by their nature, individual coronaviruses are easily destroyed. Each virus particle consists of a small set of genes, enclosed by a sphere of fatty lipid molecules, and because lipid shells are easily torn apart by soap, 20 seconds of thorough hand-washing can take one down. Lipid shells are also vulnerable to the elements; a recent study shows that the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, survives for no more than a day on cardboard, and about two to three days on steel and plastic. These viruses don’t endure in the world. They need bodies.

…

But why do some people with COVID-19 get incredibly sick, while others escape with mild or nonexistent symptoms? Age is a factor. Elderly people are at risk of more severe infections possibly because their immune system can’t mount an effective initial defense, while children are less affected because their immune system is less likely to progress to a cytokine storm. But other factors—a person’s genes, the vagaries of their immune system, the amount of virus they’re exposed to, the other microbes in their bodies—might play a role too. In general, “it’s a mystery why some people have mild disease, even within the same age group,” Iwasaki [Akiko Iwasaki of the Yale School of Medicine] says.

…

We still have a lot to learn about this.

Going nuts and finding balance with numbers

Generally speaking,. I find numbers help me to put this situation into perspective. It seems I’m not alone; Dr. Daniel Gillis’ (Guelph University in Ontario, Canada) March 18, 2020 blog post is titled, Statistics In A Time of Crisis.

Hearkening back in history, the Wikipedia entry for Spanish flu offers a low of 17M deaths in a 2018 estimate to a high of !00M deaths in a 2005 estimate. At this writing (Friday, March 20, 2020 at 3 pm PT), the number of coronovirus cases worldwide is 272,820 with 11, 313 deaths.

Articles like Michael Schulman’s March 16, 2020 article for the New Yorker might not be as helpful as one hope (Note: Links have been removed),

Last Wednesday night [March 11, 2020], not long after President Trump’s Oval Office address, I called my mother to check in about the, you know, unprecedented global health crisis [emphasis mine] that’s happening. She told me that she and my father were in a cab on the way home from a fun dinner at the Polo Bar, in midtown Manhattan, with another couple who were old friends.

“You went to a restaurant?!” I shrieked. This was several days after she had told me, through sniffles, that she was recovering from a cold but didn’t see any reason that she shouldn’t go to the school where she works. Also, she was still hoping to make a trip to Florida at the end of the month. My dad, a lawyer, was planning to go into the office on Thursday, but thought that he might work from home on Friday, if he could figure out how to link up his personal computer. …

… I’m thirty-eight, and my mother and father are sixty-eight and seventy-four, respectively. Neither is retired, and both are in good shape. But people sixty-five and older—more than half of the baby-boomer population—are more susceptible to COVID-19 and have a higher mortality rate, and my parents’ blithe behavior was as unsettling as the frantic warnings coming from hospitals in Italy.

…

Clearly, Schulman is concerned about his parents’ health and well being but the tone of near hysteria is a bit off-putting. We’re not in a crisis (exception: the Italians and, possibly, the Spanish and the French)—yet.

Tyler Dawson’s March 20, 2020 article in The Province newspaper (in Vancouver, British Columbia) offers dire consequences from COVID-19 before pivoting,

COVID-19 will leave no Canadian untouched.

Travel plans halted. First dates postponed. School semesters interrupted. Jobs lost. Retirement savings decimated. Some of us will know someone who has gotten sick, or tragically, died from the virus.

…

By now we know the terminology: social distancing, flatten the curve. Across the country, each province is taking measures to prepare, to plan for care, and the federal government has introduced financial measures amounting to more than three per cent of the country’s GDP to float the economy onward.

The response, says Steven Taylor, a University of British Columbia psychiatry professor and author of The Psychology of Pandemics, is a “balancing act.” [emphasis mine] Keep people alert, but neither panicked nor tuned out.

“You need to generate some degree of anxiety that gets people’s attention,” says Taylor. “If you overstate the message it could backfire.”

…

Prepare for uncertainty

In the same way experts still cannot come up with a definitive death rate for the 1918/19 pandemic, they are having trouble with this one too although, now, they’re trying to model the future rather than trying to establish what happened in the past. David Adam’s March 12, 2020 article forThe Scientist, provides some insight into the difficulties (Note: Links have been removed)

…

Like any other models, the projections of how the outbreak will unfold, how many people will become infected, and how many will die, are only as reliable as the scientific information they rest on. And most modelers’ efforts so far have focused on improving these data, rather than making premature predictions.

“Most of the work that modelers have done recently or in the first part of the epidemic hasn’t really been coming up with models and predictions, which is I think how most people think of it,” says John Edmunds, who works in the Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “Most of the work has really been around characterizing the epidemiology, trying to estimate key parameters. I don’t really class that as modeling but it tends to be the modelers that do it.”

These variables include key numbers such as the disease incubation period, how quickly the virus spreads through the population, and, perhaps most contentiously, the case-fatality ratio. This sounds simple: it’s the proportion of infected people who die. But working it out is much trickier than it looks. “The non-specialists do this all the time and they always get it wrong,” Edmunds says. “If you just divide the total numbers of deaths by the total numbers of cases, you’re going to get the wrong answer.”

Earlier this month, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the head of the World Health Organization, dismayed disease modelers when he said COVID-19 (the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus) had killed 3.4 percent of reported cases, and that this was more severe than seasonal flu, which has a death rate of around 0.1 percent. Such a simple calculation does not account for the two to three weeks it usually takes someone who catches the virus to die, for example. And it assumes that reported cases are an accurate reflection of how many people are infected, when the true number will be much higher and the true mortality rate much lower.

Edmunds calls this kind of work “outbreak analytics” rather than true modeling, and he says the results of various specialist groups around the world are starting to converge on COVID-19’s true case-fatality ratio, which seems to be about 1 percent.[emphasis mine]

…

The 1% estimate in Adam’s article accords with Jeremy Samuel Faust’s (an emergency medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, faculty in its division of health policy and public health, and an instructor at Harvard Medical School) estimates in a March 4, 2020 article (COVID-19 Isn’t As Deadly As We Think featured in my March 9, 2020 posting).

In a March 17, 2020 article by Steven Lewis (a health policy consultant formerly based in Saskatchewan, Canada; now living in Australia) for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) news online website, he covers some of the same ground and offers a somewhat higher projected death rate while refusing to commit,

Imagine you’re a chief public health officer and you’re asked the question on everyone’s mind: how deadly is the COVID-19 outbreak?

With the number of cases worldwide approaching 200,000, and 1,000 or more cases in 15 countries, you’d think there would be an answer. But the more data we see, the tougher it is to come up with a hard number.

Overall, the death rate is around four per cent — of reported cases. That’s also the death rate in China, which to date accounts for just under half the total number of global cases.

China is the only country where a) the outcome of almost all cases is known (85 per cent have recovered), and b) the spread has been stopped (numbers plateaued about a month ago).

A four per cent death rate is pretty high — about 40 times more deadly than seasonal flu — but no experts believe that is the death rate. The latest estimate is that it is around 1.5 per cent. [emphasis mine] Other models suggest that it may be somewhat lower.

The true rate can be known only if every case is known and confirmed by testing — including the asymptomatic or relatively benign cases, which comprise 80 per cent or more of the total — and all cases have run their course (people have either recovered or died). Aside from those in China, almost all cases identified are still active.

Unless a jurisdiction systematically tests a large random sample of its population, we may never know the true rate of infection or the real death rate.

Yet for all this unavoidable uncertainty, it is still odd that the rates vary so widely by country.

…

His description of the situation in Europe is quite interesting and worthwhile if you have the time to read it.

In the last article I’m including here, Murray Brewster offers some encouraging words in his March 20, 2020 piece about the preparations being made by the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF),

The Canadian military is preparing to respond to multiple waves of the COVID-19 pandemic which could stretch out over a year or more, the country’s top military commander said in his latest planning directive.

Gen. Jonathan Vance, chief of the defence staff, warned in a memo issued Thursday that requests for assistance can be expected “from all echelons of government and the private sector and they will likely come to the Department [of National Defence] through multiple points of entry.”

The directive notes the federal government has not yet directed the military to move into response mode, but if or when it does, a single government panel — likely a deputy-minister level inter-departmental task force — will “triage requests and co-ordinate federal responses.”

It also warns that members of the military will contract the novel coronavirus, “potentially threatening the integrity” of some units.

…

The notion that the virus caseload could recede and then return is a feature of federal government planning.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has put out a notice looking for people to staff its Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response during the crisis and the secondment is expected to last between 12 and 24 months.

…

The Canadian military, unlike those in some other nations, has high-readiness units available. Vance said they are already set to reach out into communities to help when called.

Planners are also looking in more detail at possible missions — such as aiding remote communities in the Arctic where an outbreak could cripple critical infrastructure.

…

Defence analyst Dave Perry said this kind of military planning exercise is enormously challenging and complicated in normal times, let alone when most of the federal civil service has been sent home.

“The idea that they’re planning to be at this for year is absolutely bang on,” said Perry, a vice-president at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.

…

In other words, concern and caution are called for not panic. I realize this post has a strongly Canada-centric focus but I’m hopeful others elsewhere will find this helpful.