Perhaps I’m the only one who’s disconcerted?

Here’s the research (in text form) as to why we’re watching these scampering, momentary mouse friends, from a May 10, 2021 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Amanda Morris,

Northwestern University researchers are building social bonds with beams of light.

For the first time ever, Northwestern engineers and neurobiologists have wirelessly programmed — and then deprogrammed — mice to socially interact with one another in real time. The advancement is thanks to a first-of-its-kind ultraminiature, wireless, battery-free and fully implantable device that uses light to activate neurons.

This study is the first optogenetics (a method for controlling neurons with light) paper exploring social interactions within groups of animals, which was previously impossible with current technologies.

The research was published May 10 [2021] in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

The thin, flexible, wireless nature of the implant allows the mice to look normal and behave normally in realistic environments, enabling researchers to observe them under natural conditions. Previous research using optogenetics required fiberoptic wires, which restrained mouse movements and caused them to become entangled during social interactions or in complex environments.

“With previous technologies, we were unable to observe multiple animals socially interacting in complex environments because they were tethered,” said Northwestern neurobiologist Yevgenia Kozorovitskiy, who designed the experiment. “The fibers would break or the animals would become entangled. In order to ask more complex questions about animal behavior in realistic environments, we needed this innovative wireless technology. It’s tremendous to get away from the tethers.”

“This paper represents the first time we’ve been able to achieve wireless, battery-free implants for optogenetics with full, independent digital control over multiple devices simultaneously in a given environment,” said Northwestern bioelectronics pioneer John A. Rogers, who led the technology development. “Brain activity in an isolated animal is interesting, but going beyond research on individuals to studies of complex, socially interacting groups is one of the most important and exciting frontiers in neuroscience. We now have the technology to investigate how bonds form and break between individuals in these groups and to examine how social hierarchies arise from these interactions.”

Kozorovitskiy is the Soretta and Henry Shapiro Research Professor of Molecular Biology and associate professor of neurobiology in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. She also is a member of the Chemistry of Life Processes Institute. Rogers is the Louis Simpson and Kimberly Querrey Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Neurological Surgery in the McCormick School of Engineering and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the director of the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics.

Kozorovitskiy and Rogers led the work with Yonggang Huang, the Jan and Marcia Achenbach Professor in Mechanical Engineering at McCormick, and Zhaoqian Xie, a professor of engineering mechanics at Dalian University of Technology in China. The paper’s co-first authors are Yiyuan Yang, Mingzheng Wu and Abraham Vázquez-Guardado — all at Northwestern.

Promise and problems of optogenetics

Because the human brain is a system of nearly 100 billion intertwined neurons, it’s extremely difficult to probe single — or even groups of — neurons. Introduced in animal models around 2005, optogenetics offers control of specific, genetically targeted neurons in order to probe them in unprecedented detail to study their connectivity or neurotransmitter release. Researchers first modify neurons in living mice to express a modified gene from light-sensitive algae. Then they can use external light to specifically control and monitor brain activity. Because of the genetic engineering involved, the method is not yet approved in humans.

“It sounds like sci-fi, but it’s an incredibly useful technique,” Kozorovitskiy said. “Optogenetics could someday soon be used to fix blindness or reverse paralysis.”

Previous optogenetics studies, however, were limited by the available technology to deliver light. Although researchers could easily probe one animal in isolation, it was challenging to simultaneously control neural activity in flexible patterns within groups of animals interacting socially. Fiberoptic wires typically emerged from an animal’s head, connecting to an external light source. Then a software program could be used to turn the light off and on, while monitoring the animal’s behavior.

“As they move around, the fibers tugged in different ways,” Rogers said. “As expected, these effects changed the animal’s patterns of motion. One, therefore, has to wonder: What behavior are you actually studying? Are you studying natural behaviors or behaviors associated with a physical constraint?”

Wireless control in real time

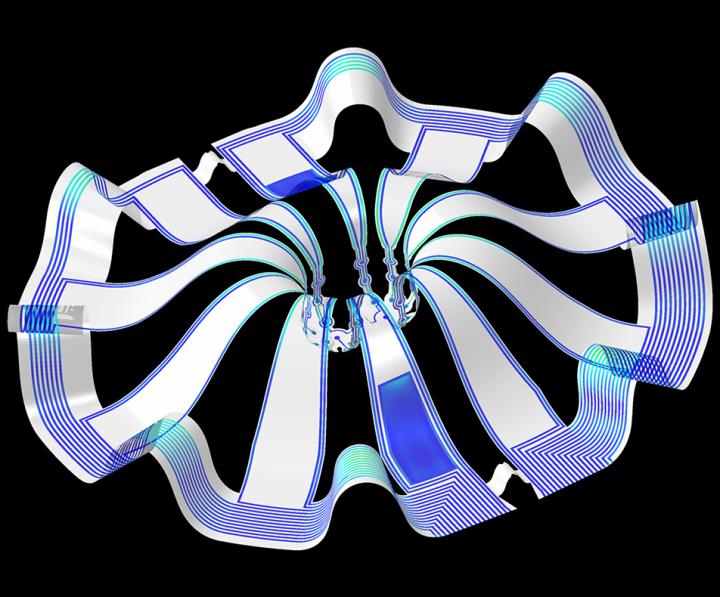

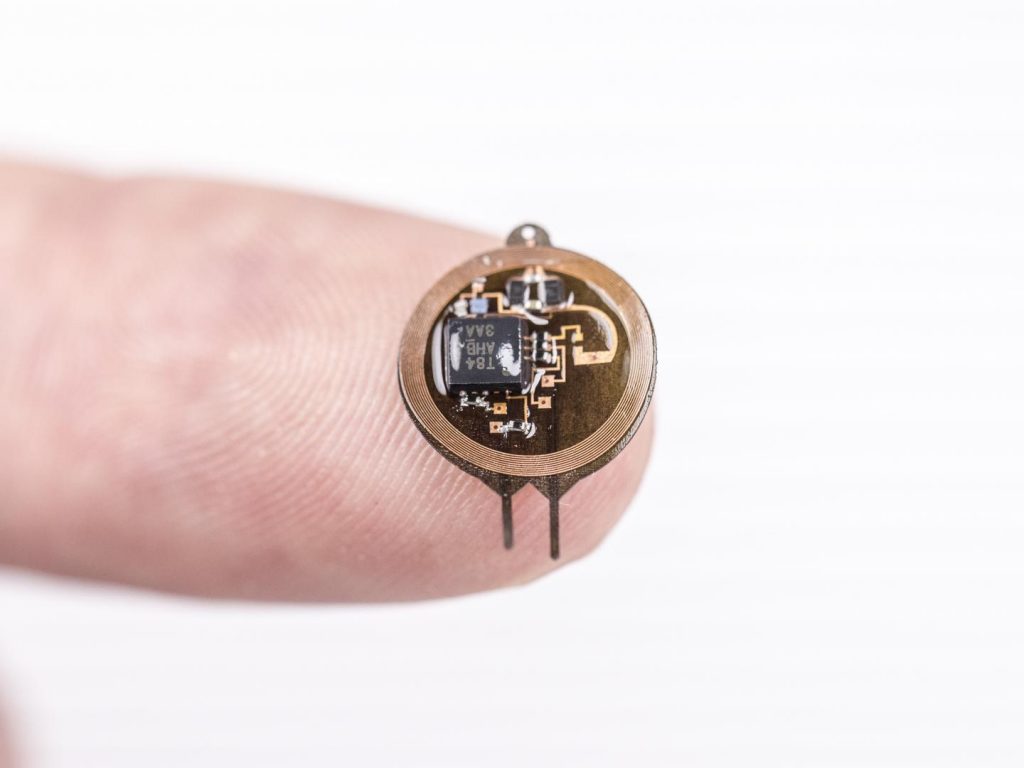

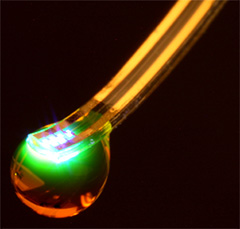

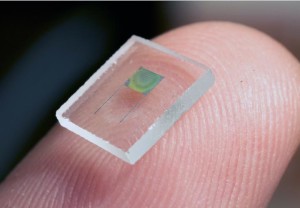

A world-renowned leader in wireless, wearable technology, Rogers and his team developed a tiny, wireless device that gently rests on the skull’s outer surface but beneath the skin and fur of a small animal. The half-millimeter-thick device connects to a fine, flexible filamentary probe with LEDs on the tip, which extend down into the brain through a tiny cranial defect.

The miniature device leverages near-field communication protocols, the same technology used in smartphones for electronic payments. Researchers wirelessly operate the light in real time with a user interface on a computer. An antenna surrounding the animals’ enclosure delivers power to the wireless device, thereby eliminating the need for a bulky, heavy battery.

Activating social connections

To establish proof of principle for Rogers’ technology, Kozorovitskiy and colleagues designed an experiment to explore an optogenetics approach to remote-control social interactions among pairs or groups of mice.

When mice were physically near one another in an enclosed environment, Kozorovitskiy’s team wirelessly synchronously activated a set of neurons in a brain region related to higher order executive function, causing them to increase the frequency and duration of social interactions. Desynchronizing the stimulation promptly decreased social interactions in the same pair of mice. In a group setting, researchers could bias an arbitrarily chosen pair to interact more than others.

“We didn’t actually think this would work,” Kozorovitskiy said. “To our knowledge, this is the first direct evaluation of a major long-standing hypothesis about neural synchrony in social behavior.”

Here’s a citation and a link to the paper,

Wireless multilateral devices for optogenetic studies of individual and social behaviors by Yiyuan Yang, Mingzheng Wu, Amy J. Wegener, Jose G. Grajales-Reyes, Yujun Deng, Taoyi Wang, Raudel Avila, Justin A. Moreno, Samuel Minkowicz, Vasin Dumrongprechachan, Jungyup Lee, Shuangyang Zhang, Alex A. Legaria, Yuhang Ma, Sunita Mehta, Daniel Franklin, Layne Hartman, Wubin Bai, Mengdi Han, Hangbo Zhao, Wei Lu, Yongjoon Yu, Xing Sheng, Anthony Banks, Xinge Yu, Zoe R. Donaldson, Robert W. Gereau IV, Cameron H. Good, Zhaoqian Xie, Yonggang Huang, Yevgenia Kozorovitskiy and John A. Rogers. Nature Neuroscience (2021)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00849-x Published 10 May 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.

This latest research seems to be the continuation of research featured here in a July 16, 2019 posting: “Controlling neurons with light: no batteries or wires needed.”