I stumbled across a very interesting US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) project (from an August 30, 2021 posting on Northwestern University’s Rivnay Lab [a laboratory for organic bioelectronics] blog),

Our lab has received a cooperative agreement with DARPA to develop a wireless, fully implantable ‘living pharmacy’ device that could help regulate human sleep patterns. The project is through DARPA’s BTO (biotechnology office)’s Advanced Acclimation and Protection Tool for Environmental Readiness (ADAPTER) program, meant to address physical challenges of travel, such as jetlag and fatigue.

The device, called NTRAIN (Normalizing Timing of Rhythms Across Internal Networks of Circadian Clocks), would control the body’s circadian clock, reducing the time it takes for a person to recover from disrupted sleep/wake cycles by as much as half the usual time.

The project spans 5 institutions including Northwestern, Rice University, Carnegie Mellon, University of Minnesota, and Blackrock Neurotech.

…

Prior to the Aug. 30, 2021 posting, Amanda Morris wrote a May 13, 2021 article for Northwestern NOW (university magazine), which provides more details about the project, Note: A link has been removed,

…

The first phase of the highly interdisciplinary program will focus on developing the implant. The second phase, contingent on the first, will validate the device. If that milestone is met, then researchers will test the device in human trials, as part of the third phase. The full funding corresponds to $33 million over four-and-a-half years.

Nicknamed the “living pharmacy,” the device could be a powerful tool for military personnel, who frequently travel across multiple time zones, and shift workers including first responders, who vacillate between overnight and daytime shifts.

…

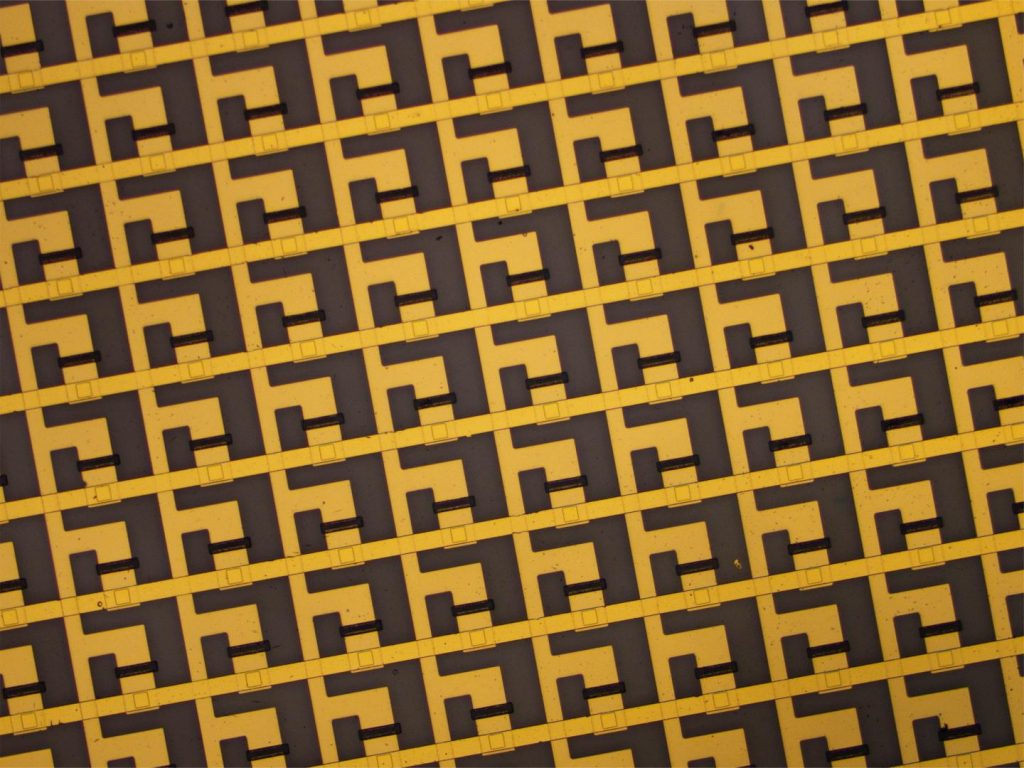

Combining synthetic biology with bioelectronics, the team will engineer cells to produce the same peptides that the body makes to regulate sleep cycles, precisely adjusting timing and dose with bioelectronic controls. When the engineered cells are exposed to light, they will generate precisely dosed peptide therapies.

“This control system allows us to deliver a peptide of interest on demand, directly into the bloodstream,” said Northwestern’s Jonathan Rivnay, principal investigator of the project. “No need to carry drugs, no need to inject therapeutics and — depending on how long we can make the device last — no need to refill the device. It’s like an implantable pharmacy on a chip that never runs out.”

…

Beyond controlling circadian rhythms, the researchers believe this technology could be modified to release other types of therapies with precise timing and dosing for potentially treating pain and disease. The DARPA program also will help researchers better understand sleep/wake cycles, in general.

“The experiments carried out in these studies will enable new insights into how internal circadian organization is maintained,” said Turek [Fred W. Turek], who co-leads the sleep team with Vitaterna [Martha Hotz Vitaterna]. “These insights will lead to new therapeutic approaches for sleep disorders as well as many other physiological and mental disorders, including those associated with aging where there is often a spontaneous breakdown in temporal organization.”

…

For those who like to dig even deeper, Dieynaba Young’s June 17, 2021 article for Smithsonian Magazine (GetPocket.com link to article) provides greater context and greater satisfaction, Note: Links have been removed,

In 1926, Fritz Kahn completed Man as Industrial Palace, the preeminent lithograph in his five-volume publication The Life of Man. The illustration shows a human body bustling with tiny factory workers. They cheerily operate a brain filled with switchboards, circuits and manometers. Below their feet, an ingenious network of pipes, chutes and conveyer belts make up the blood circulatory system. The image epitomizes a central motif in Kahn’s oeuvre: the parallel between human physiology and manufacturing, or the human body as a marvel of engineering.

An apparatus in the embryonic stage of development at the time of this writing in June of 2021—the so-called “implantable living pharmacy”—could have easily originated in Kahn’s fervid imagination. The concept is being developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in conjunction with several universities, notably Northwestern and Rice. Researchers envision a miniaturized factory, tucked inside a microchip, that will manufacture pharmaceuticals from inside the body. The drugs will then be delivered to precise targets at the command of a mobile application. …

…

The implantable living pharmacy, which is still in the “proof of concept” stage of development, is actually envisioned as two separate devices—a microchip implant and an armband. The implant will contain a layer of living synthetic cells, along with a sensor that measures temperature, a short-range wireless transmitter and a photo detector. The cells are sourced from a human donor and reengineered to perform specific functions. They’ll be mass produced in the lab, and slathered onto a layer of tiny LED lights.

The microchip will be set with a unique identification number and encryption key, then implanted under the skin in an outpatient procedure. The chip will be controlled by a battery-powered hub attached to an armband. That hub will receive signals transmitted from a mobile app.

If a soldier wishes to reset their internal clock, they’ll simply grab their phone, log onto the app and enter their upcoming itinerary—say, a flight departing at 5:30 a.m. from Arlington, Virginia, and arriving 16 hours later at Fort Buckner in Okinawa, Japan. Using short-range wireless communications, the hub will receive the signal and activate the LED lights inside the chip. The lights will shine on the synthetic cells, stimulating them to generate two compounds that are naturally produced in the body. The compounds will be released directly into the bloodstream, heading towards targeted locations, such as a tiny, centrally-located structure in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) that serves as master pacemaker of the circadian rhythm. Whatever the target location, the flow of biomolecules will alter the natural clock. When the solider arrives in Okinawa, their body will be perfectly in tune with local time.

The synthetic cells will be kept isolated from the host’s immune system by a membrane constructed of novel biomaterials, allowing only nutrients and oxygen in and only the compounds out. Should anything go wrong, they would swallow a pill that would kill the cells inside the chip only, leaving the rest of their body unaffected.

…

If you have the time, I recommend reading Young’s June 17, 2021 Smithsonian Magazine article (GetPocket.com link to article) in its entirety. Young goes on to discuss, hacking, malware, and ethical/societal issues and more.

There is an animation of Kahn’s original poster in a June 23, 2011 posting on openculture.com (also found on Vimeo; Der Mensch als Industriepalast [Man as Industrial Palace])

Credits: Idea & Animation: Henning M. Lederer / led-r-r.net; Sound-Design: David Indge; and original poster art: Fritz Kahn.