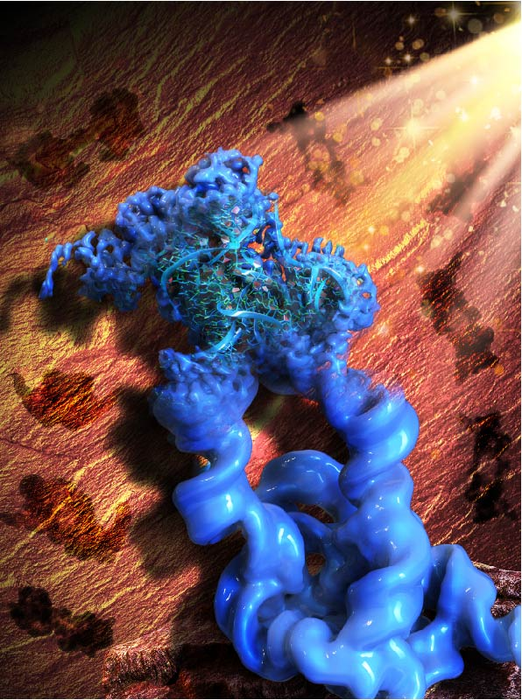

The illustration that accompanies the research is both fascinating and baffling as its caption,

This May 2, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily announces the research into RNA molecules made possible by ROCK (the technology being illustrated in the above),

We live in a world made and run by RNA [ribonucleic acid], the equally important sibling of the genetic molecule DNA. In fact, evolutionary biologists hypothesize that RNA existed and self-replicated even before the appearance of DNA and the proteins encoded by it. Fast forward to modern day humans: science has revealed that less than 3% of the human genome is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules that in turn are translated into proteins. In contrast, 82% of it is transcribed into RNA molecules with other functions many of which still remain enigmatic.

To understand what an individual RNA molecule does, its 3D structure needs to be deciphered at the level of its constituent atoms and molecular bonds. Researchers have routinely studied DNA and protein molecules by turning them into regularly packed crystals that can be examined with an X-ray beam (X-ray crystallography) or radio waves (nuclear magnetic resonance). However, these techniques cannot be applied to RNA molecules with nearly the same effectiveness because their molecular composition and structural flexibility prevent them from easily forming crystals.

Now, a research collaboration led by Wyss Core Faculty member Peng Yin, Ph.D. at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, and Maofu Liao, Ph.D. at Harvard Medical School (HMS), has reported a fundamentally new approach to the structural investigation of RNA molecules. ROCK, as it is called, uses an RNA nanotechnological technique that allows it to assemble multiple identical RNA molecules into a highly organized structure, which significantly reduces the flexibility of individual RNA molecules and multiplies their molecular weight. Applied to well-known model RNAs with different sizes and functions as benchmarks, the team showed that their method enables the structural analysis of the contained RNA subunits with a technique known as cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Their advance is reported in Nature Methods.

…

A May 2, 2022 Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Benjamin Boettner, which originated the news item, delves further into the imaging technology, Note: Links have been removed,

“ROCK is breaking the current limits of RNA structural investigations and enables 3D structures of RNA molecules to be unlocked that are difficult or impossible to access with existing methods, and at near-atomic resolution,” said Yin, who together with Liao led the study. “We expect this advance to invigorate many areas of fundamental research and drug development, including the burgeoning field of RNA therapeutics.” Yin also is a leader of the Wyss Institute’s Molecular Robotics Initiative and Professor in the Department of Systems Biology at HMS.

Gaining control over RNA

Yin’s team at the Wyss Institute has pioneered various approaches that enable DNA and RNA molecules to self-assemble into large structures based on different principles and requirements, including DNA bricks and DNA origami. They hypothesized that such strategies could also be used to assemble naturally occurring RNA molecules into highly ordered circular complexes in which their freedom to flex and move is highly restricted by specifically linking them together. Many RNAs fold in complex yet predictable ways, with small segments base-pairing with each other. The result often is a stabilized “core” and “stem-loops” bulging out into the periphery.

“In our approach we install ‘kissing loops’ that link different peripheral stem-loops belonging to two copies of an identical RNA in a way that allows a overall stabilized ring to be formed, containing multiple copies of the RNA of interest,” said Di Liu, Ph.D., one of two first-authors and a Postdoctoral Fellow in Yin’s group. “We speculated that these higher-order rings could be analyzed with high resolution by cryo-EM, which had been applied to RNA molecules with first success.”

Picturing stabilized RNA

In cryo-EM, many single particles are flash-frozen at cryogenic temperatures to prevent any further movements, and then visualized with an electron microscope and the help of computational algorithms that compare the various aspects of a particle’s 2D surface projections and reconstruct its 3D architecture. Peng and Liu teamed up with Liao and his former graduate student François Thélot, Ph.D., the other co-first author of the study. Liao with his group has made important contributions to the rapidly advancing cryo-EM field and the experimental and computational analysis of single particles formed by specific proteins.

“Cryo-EM has great advantages over traditional methods in seeing high-resolution details of biological molecules including proteins, DNAs and RNAs, but the small size and moving tendency of most RNAs prevent successful determination of RNA structures. Our novel method of assembling RNA multimers solves these two problems at the same time, by increasing the size of RNA and reducing its movement,” said Liao, who also is Associate Professor of Cell Biology at HMS. “Our approach has opened the door to rapid structure determination of many RNAs by cryo-EM.” The integration of RNA nanotechnology and cryo-EM approaches led the team to name their method “RNA oligomerization-enabled cryo-EM via installing kissing loops” (ROCK).

To provide proof-of-principle for ROCK, the team focused on a large intron RNA from Tetrahymena, a single-celled organism, and a small intron RNA from Azoarcus, a nitrogen-fixing bacterium, as well as the so-called FMN riboswitch. Intron RNAs are non-coding RNA sequences scattered throughout the sequences of freshly-transcribed RNAs and have to be “spliced” out in order for the mature RNA to be generated. The FMN riboswitch is found in bacterial RNAs involved in the biosynthesis of flavin metabolites derived from vitamin B2. Upon binding one of them, flavin mononucleotide (FMN), it switches its 3D conformation and suppresses the synthesis of its mother RNA.

“The assembly of the Tetrahymena group I intron into a ring-like structure made the samples more homogenous, and enabled the use of computational tools leveraging the symmetry of the assembled structure. While our dataset is relatively modest in size, ROCK’s innate advantages allowed us to resolve the structure at an unprecedented resolution,” said Thélot. “The RNA’s core is resolved at 2.85 Å [one Ångström is one ten-billions (US) of a meter and the preferred metric used by structural biologists], revealing detailed features of the nucleotide bases and sugar backbone. I don’t think we could have gotten there without ROCK – or at least not without considerably more resources.”

Cryo-EM also is able to capture molecules in different states if they, for example, change their 3D conformation as part of their function. Applying ROCK to the Azoarcus intron RNA and the FMN riboswitch, the team managed to identify the different conformations that the Azoarcus intron transitions through during its self-splicing process, and to reveal the relative conformational rigidity of the ligand-binding site of the FMN riboswitch.

“This study by Peng Yin and his collaborators elegantly shows how RNA nanotechnology can work as an accelerator to advance other disciplines. Being able to visualize and understand the structures of many naturally occurring RNA molecules could have tremendous impact on our understanding of many biological and pathological processes across different cell types, tissues, and organisms, and even enable new drug development approaches,” said Wyss Founding Director Donald Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

The study was also authored by Joseph Piccirilli, Ph.D., an expert in RNA chemistry and biochemistry and Professor at The University of Chicago. It was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF; grant# CMMI-1333215, CCMI-1344915, and CBET-1729397), Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR; grant MURI FATE, #FA9550-15-1-0514), National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant# 5DP1GM133052, R01GM122797, and R01GM102489), and the Wyss Institute’s Molecular Robotics Initiative.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Sub-3-Å cryo-EM structure of RNA enabled by engineered homomeric self-assembly by Di Liu, François A. Thélot, Joseph A. Piccirilli, Maofu Liao & Peng Yin. Nature Methods (2022) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01455-w Published: 02 May 2022

This paper is behind a paywall.